Guest post by JYOTI RAHMAN

Singing Amar Shonar Bangla with the whole stadium — the highest point during a cricket match attended by fellow blogger Rumi Ahmed.

For those of us born in Bangladesh, which turns 40 today, along with the red-and-green flag, there is an instinctive, natural identification with Amar Shonar Bangla. Less recognised is the fascinating history of the song, which also tells us the twists and turns in the history of the 20th century Bengal.

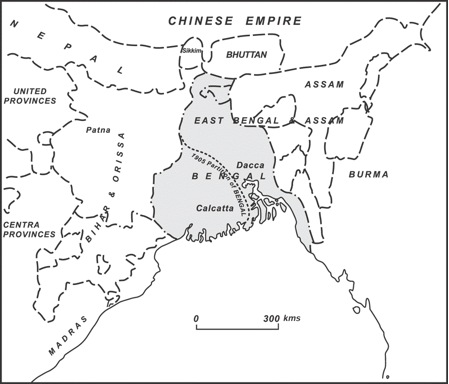

Tagore wrote Amar Shonar Bangla in 1906 to the first partition of Bengal. The partition created a new province of East Bengal and Assam — consisting largely of today’s Bangladesh and the Indian northeast. At the risk of oversimplification, Muslims supported the scheme while Hindus opposed it. The scheme was annulled in 1912.

As the song protests the partition scheme, it could not have been very popular among Bengali Muslims. Another protest song of the era, Vande Mataram, was very unpopular among Muslims because it was from a novel about ridding Bengal, and India, of Muslim ‘invaders’.

In Vande Mataram, the land is identified with the Mother Goddess, and veneration of the Mother Goddess is contrary to the fundamental tenet of Islam. As it happens, Amar Shonar Bangla also compares Bengal with the Mother. To the early 20th century Bengalis, Hindu or Muslim alike, the Mother meant the Mother Goddess. But unlike Bankim Chandra Chaterjee, the author of Vande Mataram, Tagore explicitly rejected linking his politics with Hindu iconography.

In fact, he was acutely aware of the way the anti-partitionists alienated the region’s Muslim majority. In his 1916 novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World), Tagore shows a Hindu leader — played by Soumitra Chaterjee in the 1984 Satyajit Ray adaptation — forcing Muslim peasants into boycotting British goods even when local goods were much more costly, the local peasants had no stake in the leader’s cause and even when the leader himself couldn’t give up British cigarettes.

In his later years, Tagore urged Hindu-Muslim amity. But we know that this was not to be. Bengal was partitioned again in 1947, this time with the acceptance of both communities. And no one sang Amar Shonar Bangla in the 1940s.

The eastern half of Bengal became Pakistan’s eastern wing. By March 1948, first rumblings of a Bangla nationalism could be heard in the form of the language debate. There were political crisis throughout the 1950s, leading to the Ayub regime of 1958. There were debates about political autonomy, about foreign policy, about socialism.

And then in the early 1960s, Bengali intellectuals and cultural activists defied government bans on commemorating Tagore’s 100th birth anniversary and celebrating the Bangla new year. This was a milestone moment in the cultural history of Bangladesh. The Ayub regime, in an effort to create a Pakistani nation, dubbed Tagore a Hindu poet whose writing would pollute the pure (Pak) mind and soul. The urban educated class of East Pakistan overwhelmingly adopted Tagore as their own.

And in another decade, Bangladesh was fighting its war of liberation against the Pakistan army. And the land as the Mother, but quite clearly not the Mother Goddess, was a central theme in the cultural iconography of the Bangladesh movement. The Shaheed Minar symbolises a mother with her children, for example.

In early 1971, radical students chose Amar Shonar Bangla as Free Bengal’s national anthem, and when the war ended, the new republic’s leaders endorsed it. Why did they choose the song? For that matter, why did they choose the red and green flag?

From all accounts, the song was chosen because of its evocation of the rural landscape — mango groves and paddy fields, perennial features of Mother Bengal. And that’s what the green in the flag meant to the more radical students, though for others green symbolised Islam. But it was stressed that everyone was very conscious about choosing inclusive icons.

This contrasts sharply with Bangladesh’s neighbours. The Pakistan Movement adopted the crescent, unsurprisingly alienating all non-Muslims in the lands that became Pakistan. Indian nationalism claimed to be inclusive, espousing secularism as a fundamental value. But Gandhi’s Ram Rajya did not appeal to Muslims, nor did the spinning wheel, which everyone thought symbolised eternal — that is, pre-Islamic — India (quite ironic, really, as according to Irfan Habib, the earliest known reference to the spinning wheel in South Asia is a 1350 polemic urging Raziya Sultana to give up Delhi’s masnad and take up spinning, the ‘inescapable inference’ being the device having a Muslim provenance).

So, Bangladesh made a conscious effort of being inclusive at its foundation. Something to celebrate on its 40th birthday, surely?

Yes, it is, but…

Bangladesh’s founders may have tried to be relatively more inclusive, but in an absolute sense, there were, and are, plenty of blind spots in Bangladeshi nationalism. The most egregious blind spot is, of course, the Adibashis — who are not even recognised as such. Right now, there is a multi-party parliamentary committee that is tasked with amending the Constitution to reflect the ‘spirit of the Liberation War’. And the committee says that there is no such thing as Adibashi in Bangladesh — there are Bengalis, and there are ‘ethnic minorities’. Ironically, only a month ago, at the World Cup cricket opening ceremony, Adibashi dances were show-cased to win tourist Dollars (and Rupees).

Then there are Bengalis who are not Muslims.

Bangladesh’s Constitution claimed secularism to be a high ideal of the republic in 1972. But successive military regimes introduced the invocation Bismillah, faith in almighty Allah, and Islam as the state religion in the constitution, while secularism was junked. Last year, a court verdict restored secularism. Yet Islam remains the state religion, as does Bismillah. And Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina categorically promises that Islam will stay in the Constitution, even as the forthcoming amendment makes Bangladesh a secular republic.

Now, one can argue that the political reality of Bangladesh is such that Islam has to be acknowledged somehow in the Constitution, that ‘Islamic secularism‘ is the only type of secularism that can survive in Bangladesh. This is because, if the idea of secularism, and the related values of pluralism and liberalism, are to flourish anywhere, it has to be in accordance with the norms and values of that society. And secularism/pluralism in Bangladesh will have to spring from the Bengali Muslim identity.

There is a lot to be said about this argument. But the moment one takes this line, one essentially says Bangladesh is really the national homeland of the Bengali Muslim people, and the argument is really about how much rights the Others should have (in theory as well as in practice).

That’s not really an inclusive vision, is it?

It gets even more complicated. If we downplay the nationalist line, and genuinely, sincerely, want an inclusive vision, we run into another problem. If Bangladesh is about a place for all the peoples of this land, and India is also a noble mansion where all her children could dwell, then why Bangladesh?

Think about that for a minute. Tagore wrote Amar Shonar Bangla. But he also wrote Bharat Teertha. If Scythians, Huns, Pathans, Mughals were all supposed to immerse into the teeming multitude of India according to Tagore, and if Tagore was one of us, then why can’t we also immerse ourselves in India?

Why Bangladesh, and not India? There is a nationalist answer to it. Is there a non-nationalist answer?

It is possible to have a non-nationalist answer. It is possible to say that the Indian republic, the Indian democracy, is not working, has not been working, for its marginalised. It is possible to say that a smaller state, a state that is more proximate to its citizens, can be more democratic — in the real sense of the word. It is possible to say that a People’s Republic can do better than the Indian Union.

Is it possible to say that the People’s Republic of Bangladesh can do better?

I can’t yet answer that in the affirmative, and on this fortieth year of Bangladesh’s independence, my wish is that at least a decade from now the answer would be Yes.

Previously by Jyoti Rahman in Kafila:

More on Bangladesh from Kafila archives:

What a fabulous piece Jyoti.

But…

You write: “It is possible to have a non-nationalist answer. It is possible to say that the Indian republic, the Indian democracy, is not working, has not been working, for its marginalised. It is possible to say that a smaller state, a state that is more proximate to its citizens, can be more democratic — in the real sense of the word. It is possible to say that a People’s Republic can do better than the Indian Union.”

In other words, the raison d’etre of India’s neighbours and their nation-state-ness is to be India’s failure. May I humbly say that as a ‘non-nationalist’ Indian, I do really hope that is not the case, and most certainly, a lot of people here are hoping and trying to make the Indian Republic work, and save it from the Indian Union. Yet, perhaps like you, I can only say that I want to be able to say, a decade from now, that we’ve been succeeding.

And while I say that, the worst case scenario that comes to mind: what if we all fail!

My greetings on 40 years of Bangladesh :)

LikeLike

Thanks bro for posting it. It would be very unfortunate if we take the message as ‘Bangladesh, because India is a failure’. Rather, the message should be — ‘Bangladesh, because it can do better than India’. While we all fear ‘what if we all fail’, we could also rededicate ourselves to ‘we will all succeed, together’.

And let me stress the ‘together’ bit. The language of nationalism is one of competition and zero sum games. Any gain to me must be at the expense of you. But it doesn’t need to be this way. Progressives from across the border can learn a lot from each others experience. We in Bangladesh have a lot to learn from the Indian activists when it comes to projecting a strong progressive voice that is not beholden to party politics.

LikeLike

Bangladesh is killing/humiliating/converting Hindus to Islam. No one talks about the plight of hapless Hindus, victims of genocide there.

LikeLike

Wonderful and thought provoking article for Ms.Jyoti Rahman. Unfortunately, It will take couple of generations to forget the difficult past we all had to share. And only at that time people may be realist and see to reasons to shape the countries according to their desire.

LikeLike

Dr Pandey, your comment is wrong on two accounts.

Firstly, it is untrue that no one talks about the plight of Hindus (and other ethnic/religious minorities) in Bangladesh. Here is a concrete, specific example:

http://www.drishtipat.org/past/cheyedekho/index.html

Further, Drishtipat Writers’ Collective — a group of progressive writers — I belong to, has written a lot on the subject, as have many others over the years.

Has our activism been sufficient? Patently not. It is unfortunately not the case that People’s Republic of Bangladesh, in practice, belongs to all its people. This regrettable reality was not washed away in the post. But we are working hard, as are Shivam and his comrades in this blog (and elsewhere) towards making the Indian Republic work.

Unfortunately, the second and bigger inaccuracy in your comment will make our task difficult. Contrary to what you say, there is no genocide of Hindus in Bangladesh. Since the dark days of post-election violence in 2001, things have improved. There is no large scale, forced conversion that you speak of. Further, genocide is a very loaded term, and it probably would be inaccurate to describe the violence in 2001 (or post-Ayodhya violence in 1992-93) as genocide.

Except of the events of 2001 or 1992-93, the plight of Hindus in Bangladesh usually does not involve mass conversion or genocide or other such events that can garner media attention. It involves mundane stuff like land grab by neighbours, denial of services by the local bureaucrat, lack of promotion at jobs etc. These may not make as exciting a soundbite as genocide, but the effects are bad nonetheless.

These ought to be fought on both sides of the border, and good faith co-operation is essential. Nationalist rhetoric of ‘my country is better than yours’, on the other hand, is counterproductive.

—

Sadman2901, thanks for the kind words.:)

I read somewhere that these days, cultural changes are happening so fast that generation passes in a decade. If so, couple of generations are not that far away. Let’s be hopeful.

LikeLike

‘This is because, if the idea of secularism, and the related values of pluralism and liberalism, are to flourish anywhere, it has to be in accordance with the norms and values of that society. And secularism/pluralism in Bangladesh will have to spring from the Bengali Muslim identity.’

If any one says a similar thing in India and argue that secularosm in India will have to spring from Hindu identity (s)he would be branded as fascist, hindudtva ideologue etc. You write as if there is no other language in Bangladesh.You are arguing that pluralism and liberalism cannot flourish otherwise.Why? Does it mean that liberalism will have to compatible with sharia and concepts like kafir.Do Canada/USA?UK impose christian norms on liberalism. They dont.So what prevents you from arguing that secularism can be secularism per se without the need to spring from any linguistic/faith based identity.

LikeLike

an indian, it would help if you bothered to read entire paragraphs rather than coming in with your blinding prejudices and selectively picking out random words:

That passage you quote above says that those who argue for ‘islamic secularism’ could make that argument, but goes on to say in the very next line: “But the moment one takes this line, one essentially says Bangladesh is really the national homeland of the Bengali Muslim people, and the argument is really about how much rights the Others should have (in theory as well as in practice).

That’s not really an inclusive vision, is it?”

In other words, to spell it out, since you seem to have comprehension problems, the author is saying precisely that such an argument is unacceptable.

But I dont know why I’m bothering. Your indian-ness and your bigotry seem to be directly proportional to each other, and you dont really care what was actually argued by the Bangladeshi.

LikeLike

Great post, thanks. But the song come off quite badly mainly due to someone singing it highly tunelessly in the foreground, almost like a parody! (Ironically, the crowd sounded more in tune). Just for the record, here’s a more intelligible vocal version: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVjbVPFeo2o , and an oddly militarized but well-harmonized orchestral arrangement: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmJHRWVYctA&feature=fvwrel

LikeLike

Nivedita, thanks for reiterating my argument so succinctly. AD, I wanted to capture the spontaneity of the crowd with the video. Thanks for better renditions.

LikeLike

This is an interesting and reflective piece. The nationalism of Bangladesh mirrors the European nation-state model very closely, one language and (almost) one religion. But then again, even in Europe, with increasing diversity, the ethnicity based nation state model is being increasingly displaced by civic nationalisms.

The author offers an attractive metric for thinking about why Bangladesh should have come into existence. But the development and proximate state hypothesis is easily invalidated by looking at Kerala and Tamil Nadu on the one hand, and UP on the other. Even though UP is much more proximate to the center on account of its location and the number of seats in Parliament, it is far less developed than either of these supposedly distant states.

No one would doubt that a more proximate state would, in general, be more responsive to people. But the question that needs to be thought about is whether this state necessarily needs to be a nation-state, or whether it can be a state in a federation.

LikeLike