“Here lies buried Saadat Hasan Manto in whose bosom are enshrined all the secrets and art of short story writing. Buried under mounds of earth, even now he is contemplating whether he is a greater short story writer or God.”

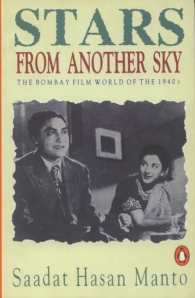

May 2012 will mark the hundredth birth anniversary of the man who wrote that epitaph for himself, Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955). One cannot help but compare Manto’s centennial to Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s last year, preparations for which had begun much in advance. There seems to be an odd silence about Manto.

Where would we be without Manto? He died in 1955 but lives on in the hearts of millions of people in both Pakistan in India because his work has by now helped generations understand, and if I may say so, come to terms with the Partition of 1947 whose ghosts haven’t left us yet. Manto’s centrality in understanding Partition remains despite a growing body of historical research on the subject. We must be grateful, also, to all those who have translated and transliterated his work into English, Hindi and other languages. Much of his English translation, though not the best, is by his nephew Khalid Hasan, who passed away a few years ago.

He wrote, amongst a lot of other material, 200 short stories. The most famous is Toba Tek Singh, about the India-Pakistan exchange of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, set in a mental asylum in Lahore. Gratitude is due to those who invented YouTube, thanks to which one can hear the great Pakistani actor Zia Mohyeddin recite Toba Tek Singh:

*

In a tribute to the story, the Bollywood lyricist Gulzar once wrote these lines:

mujhe wagah pe toba tek singh wale ‘bishan’ se ja ke milna ha

suna ha woh abhi tak suuje paeroon per khada ha

jis jagah ‘munto’ne choda tha usewoh aab tak boodbadata ha

‘uppar di gur gur di moong di daal di laalten’pata lena ha us pagal ka

oonchi daal per chad kar jo kehta haikhuda hai woh use faisla karna hai kis ka gaon kis ke hisse mein ayega

woh kab ootrega apni daal se us ko batana haabhi kuch aur bhi dil hain k jin ko baantne ka, kaatne ka kaam zari hai

woh batwara toh pehle tha abhi kuch aur batware baki hainmujhe wagah pe toba tek singh wale bishan se milna hai

khabar deni ha us ke dost afzal ko

woh ‘lehna singh’,’wadawa singh’ woh ‘bhen amrit’

woh saare qatl ho kar is tarf aye theun ki gardnein saman hi mein lutt gayeein peeche

zabah kar de woh’bhoori’ ab koi leene na ayegawoh ladki ik oongli jo badi hoti thi her barah mahine mein

woh ab har ik bars ik pota pota ghatti rehti habatana ha k sab pagal poohche nahin apne thikanoon per

bahut se is taraf bhi hain bahut se us taraf bhi haimujhe wagah pe toba tek singh wala bishan aksar yehi keh ke bolata hai

“uppar di gurr gurr di moong daal di laltein di hinustan te pakistan di durr fithe moonh”

A translation by Anisur Rahman (from Translating Partition, Ed. Ravikant and Tarun K. Saint).

I’ve to go and meet Toba Tek Singh’s Bishan at Wagah

I’m told he still stands on his swollen feet

Where Manto had left him,

He still mutters:

Opad di gud gud di moong di dal di laltainI’ve to locate that mad fellow

Who used to speak up from a branch high above:

“He’s god

He alone has to decide – whose village to whose side.”When will he move down that branch

He is to be told:

“There are some more – left still

Who are being divided, made into pieces –

There are some more Partitions to be done

That Partition was only the first one.”I’ve to go and meet Toba Tek Singh’s Bishan at Wagah,

His friend Afzal has to be informed –

Lahna Singh, Wadhwa Singh, Bheen Amrit

Had arrived here butchered –

Their heads were looted with the luggage on the way behind.Slay that “Bhuri”, none will come to claim her now.

That girl who grew one finger every twelve months,

Now shortens one phalanx each year.It’s to be told that all the mad ones haven’t yet reached their destinations

There are many on that side

And many on this.Toba Tek Singhís Bishan beckons me often to say:

“Opad di gud gud di moong di dal di laltain di Hindustan te Pakistan di dur fitey munh.“

Marking the centennial, Tariq Ali pays tribute to the master:

Manto was amongst the few who observed the bloodbaths of Partition with a detached eye. He had remained in Bombay in 1947, where he worked for the film industry, but was accused of favoring Muslims and was subjected to endless communal taunts, even from those who had hitherto imagined to be like him, but the secular core in many people did not survive the fire. Manto came to Lahore in 1948, but was never happy. He turned the tragedies he had witnessed or heard into great literature. He wrote of the common people, regardless of ethnic, religious or caste identities and he discovered contradictions and passions and irrationality in each of them. In his work we see how normally decent people can, in extreme conditions, commit the most appalling atrocities. ‘Cold Meat’ is one such story.

In 1952 he wrote: “My heart is heavy with grief today. A strange listlessness has enveloped me. More than four years ago when I said farewell to my other home, Bombay, I experienced the same kind of sadness…” [Counterpunch]

Manto is a celebrated figure in Pakistan today – and if you do a YouTube search for his name the number of Pakistani news TV reports on his death anniversary will tell you that he is probably given more due in Pakistan than in India. Like this one in GEO news:

However, he also remains “unpalatable”. The Karachi-based scholar Ajmal Kamal has written a series of articles on the unpalatable Manto:

The Safety Act had well-known literary people on both sides. On the one hand, literary critics such as Muhammad Hasan Askari found the law perfectly justifiable — indeed, he went so far as to praise it in his column which appeared under the running title “Jhalkian” in the (obviously and openly anti-progressive) literary periodical Saqi — published from Delhi until June 1947, and subsequently from Karachi. On the other hand, there were writers and editors who were prosecuted under this law, Manto perhaps being the most prominent among them. Manto wrote a scathing piece against the Safety Act and the actions taken under it. [Link]

In the second piece, Kamal looks up the Urdu textbook for school students in Sindh to find that thy have included Manto’s story Naya Qanoon but have deleted some portions within:

I reproduce below — in italics — the portions of ‘Naya Qanoon’ that the great, respectable (and, no doubt, highly educated) minds manning the editorial committees dutifully serving the Sindh Textbook Board thought it necessary to delete from it texts, followed by my own comments as an attempt to understand the above-mentioned minds.

“One day he [Mangu] overheard a couple of his fares discussing yet another outbreak of communal violence between Hindus and Muslims.

“That evening when he returned to the adda, he looked perturbed. He sat down with his friends, took a long drag on the hookah, removed his khaki turban and said in a worried voice: “It is no doubt the result of a holy man’s curse that Hindus and Muslims keep slashing each other up every other day. I have heard it said by one of my elders that Akbar Badshah once showed disrespect to a saint, who cursed him in these words: ‘Get out of my sight! And, yes, your Hindustan will always be plagued by riots and disorder.’ And you can see for yourselves. Ever since the end of Akbar’s raj, what else has India known but riots!”

The entire second paragraph has been expunged. This is in line with the official policy to present the Hindu-Muslim riots in the erstwhile united India as a one-way affair and the Muslims as innocent victims and never as equal, or equally enthusiastic, partners in the game of riots. [The Express Tribune]

Kamal goes to to quote and analyse more expunged words from that story in his third column.

Manto was a problem for the best of people even during his lifetime, but amongst his defenders was Faiz Ahmed ‘Faiz’. Ali Madeeh Hashmi writes in the Pakistani journal Viewpoint:

Soon though, his voice veered towards his chosen themes, relationships, the ‘mysterious working of the human psyche, the hidden (and often denied) motives behind human actions’ and the reactions of men and women to societal and established taboos. In this, he had more in common with the arch-opponents of the Progressives, the ‘Halqa-e Arbab-e Zauq’ (‘Circle of the friends of taste’) spearheaded by two other free spirits, the poets NM Rashed and Sana-Ullah Dar ‘Mira-ji’. Very soon, he was declared a ‘reactionary’ and a ‘modernist’, the terms used in opposition to ‘Progressive’ in those days. Manto himself defended himself against these charges ‘the biggest complication is about this Progressive literature although it shouldn’t be. Literature is either literature or not, Man is either Man or not, he cannot be a donkey or a house or a table. People say Manto is a Progressive, what rubbish. Saadat Hasan Manto is a human being and every human should be progressive….I am in favor of progress in all walks of life. I want this for everyone; you are students, I want you to progress till you reach your ideal’

Faiz defended Manto against the charges leveled against him by the Progressives, not necessarily because he admired Manto’s art and his convictions (which he did, to some extent) but because he believed that freedom of speech and expression was a basic human right and should be defended at all costs. He wrote ‘…some people (members of the Progressive movement) moved towards emotional extremism and because of this…we restricted our circle. On principle, we should have focused on the ideas of writers and artists, we should not have tried to interfere with their creativity. By doing this, we lost writers like Manto, Ismat (Chughtai) and Qurrat-ul-Ain Hyder to which I was opposed’. Ironically, Faiz, a maverick himself also later separated himself from the Progressive movement because of this same ‘meaningless extremism’ and what another Progressive historian and Faiz’ lifelong friend Sibte-Hasan, referred to as ‘literary terrorism’ on the part of the Progressives. [Full text]

It is not only Manto’s work but even his life that has become contentious for Pakistan:

When historian Ayesha Jalal said Manto became an alcoholic after migrating to Lahore from Bombay, some in the audience perhaps saw an anti-Pakistan narrative in the making. “That is stupid,” a middle-aged woman whispered to a much younger man sitting next to her. “That doesn’t make any sense. Manto was always an alcoholic,” the young man replied without looking at the woman. “That has nothing to do with Pakistan.” [Sajid Hussain]

To get some insight directly from Ayesha Jalal, listen to this interview of his niece Ayesha Jalal, who is also writing a biography of Manto. Jalal says in that interview how Manto’s non-fiction is equally important, and not just his letters to Uncle Sam that amazingly predicted the future of Pakistan-US relations.

In his third Letter to Uncle Sam, he wrote:

Uncle, I am surprised that I am still alive, although it is five years since I have been drinking the poison distilled here. If you ever come here, I will offer you this vile stuff and hope that like me you will also remain alive, along with your five freedoms. [Full text]

Manto did make peace with Partition even if he drank himself to death in Lahore. If there are any fellow-Indians who think of Manto as a Pakistani anti-hero, please read this letter of his to Nehru some months before he died, published as a preface to one of his books:

Between us Pundit brothers, do this: call me back to India. First I’ll help myself to shaljam shabdeg at your place and then take over the responsibility for Kashmiri affairs. The Bakhshis and the rest of them deserve to be sacked right away. Cheats of the first order. For no reason you’ve given them such high status. Is that because this suits you? But why at all…? I know you are a politician, which I am not. But that does not mean I don’t understand anything.

The country was partitioned. Radcliffe put Patel to do the dirty work. You’ve illegally occupied Junagarh, which a Kashmiri could do only under the influence of a Maratha. I mean Patel. (God forgive him!) [Full text]

While you’re at it, also read his take on the Hindi-Urdu debate. There can’t be a more succinct, scathing summary of the volumes that have been written on the subject.

Manto’s sister thought, perhaps wisely, that some in God’s own country may not have the sense of humour stomach a writer compare himself to God. She had the tombstone replaced with another that has these words: “Yahan Manto dafan hay jo aaj bhi ye samajhta hay kay wo loh-e-Jahan per harf-e-muqarar nahi tha (Here lies buried Manto who still believes that he was not the final word on the face of the earth).”

That revelation comes from Naila Inayat’s interview of Manto’s daughter Nighat, who speaks of life after his passing away:

For Safiyah [Manto’s wife] what the government of Pakistan did was more painful than his death. None of his published stories was rewarded. When my mother used to stop her from drinking Aba would say, “Safu gee tanu gadi wi koi masla nai huey ga” (you will never face any financial issues). He thought he was leaving so much behind that the family would never ever face any trouble but he was always banned. And interestingly, that’s still the case.

…today’s TV plays are showing everything, from physical intimacy to bold storylines. But none of his plays is adapted on TV. Ptv has done a few but none was a quality production. I don’t understand why anybody doesn’t want to do a Manto play – is it because of the ban that people are afraid to work on him. His story ‘Bu’ is so powerful, you get involved in its script, and I don’t see any vulgarity in it. [Viewpoint]

very good,and exhaustive,tribute.thanks.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on And as she thinks….

LikeLike

Many, Many Thanks

LikeLike

Shivam, this is a really good compilation, thanks for it. Two things struck me however. First, unless things have changed in the last five years, Manto is actually not celebrated in Pakistan. His books were impossible to find in shops in Lahore and his daughter confirmed for us that there was indeed some amount of suspicion around him as a figure and his works were definitely treated like ticking bombs (which they are!).

Secondly, I am pretty sure that the image of the tomb that you have is not in fact the right one. I went to his grave in Lahore (his daughter took us) and it is as plain and unadorned as can be. Forget the epitaph, even his name was not on it. Like most Islamic graves, it was difficult to identify. Unless of course they have redone it in the last few years.

LikeLike

Is this true Shivam?

LikeLike

Dear Kuhu,

Thanks for your comments. I haven’t been to Pakistan so I am sure you’d know better – but from what I see of Manto in the Pakistani web space, including crucially mainstream news channels like GEO which are not known to be left-liberal in Pakistan, I’d say Manto *is* celebrated in Pakistan, even as some of his texts are not available in Pakistan etc. I am more certain about your second query, because I got the picture from an interview of Manto’s daughter http://www.viewpointonline.net/we-dont-want-to-cash-in-on-manto-nighat-manto.html and also saw the picture in a Facebook group dedicated to Manto.

best,

shivam

LikeLike

Thank you,for clarification.

LikeLike

All I can say is that I suppose they might have changed it to something more identifiable in recent years. I went in 2005, it’s been a while. I’ll try to find the photographs and may be upload on facebook. Unfortunately, I am not in touch with the lady anymore. But it’s not that important at the end of the day!!

Once again, many thanks for a great resource!

Kuhu

LikeLike

kuhutanvir @DilliDurAst the photo of the grave is an original one, in fact only yesterday Nighat Manto told me that it has now been redone with the marbles now.

LikeLike

A fitting prelude to Manto’s centenary

LikeLike

Very descriptive and informative piece on Manto, but I think it ended quite abruptly.

LikeLike

Very true.

LikeLike

ending abhi baaki hai :)

LikeLike

Manto Afsane ki Duniya ka Khuda tha.

LikeLike

Manto is an over-rated writer. He is an icon for people who think of themselves as progressive, but as a writer, he was second rate. I’ll bet no one here has actually read Manto. That’s because he is very boring. You can read him out of some sort of duty, but not for the joy of reading literature.

We grew up seeing communal riots. It’s not like we need to read about it in fiction for its horror to sink in. This is all bogus worship of some dubious writer.

I don’t know if this comment will see the light of day. They don’t like non-conformists here.

LikeLike

A big laugh on this letter:HA HA HAAAAAAA!!!

LikeLike

So I wasn’t the only one who found him funny :)

LikeLike

But there is nothing on Manto’s literary prowess in this post. The following is the only reference to his art:

“He wrote, amongst a lot of other material, 200 short stories. The most famous is Toba Tek Singh, about the India-Pakistan exchange of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, set in a mental asylum in Lahore.”

But there is a lot of stuff about Manto as a political symbol. This is how it is always. Nobody I know has read Manto, though he has many admirers. Whenever I come across somebody speaking admiringly of Manto, I ask “What have you read by Manto?” They look around shiftily and change the subject. The guy is unreadable, except by masochists, maybe.

LikeLike

I read Manto’s letter to Uncle Sam. It is the self-indulgent bullshit of an alcoholic. If this is supposed to be the stuff of literature and wisdom, God save us all!

LikeLike

another ha ha ha!!!

LikeLike

I’m not sure what sort of literature you find amusing. How can you not laugh while reading stories such as the one on the guy whose widowed father-in-law can’t stop ogling at his new daughter-in-law, or the guy who fell head-over-heals in love with a girl only to find after marriage he cannot bear her halitosis, or the guy who left his wife to marry a nymphomaniac and walks out of his house everytime covered in scratches. Anyways, please do read his many essays on the Bombay Film Industry. The ones on Nargis, Shyam, and Ashok Kumar are my favorites. And then his essays on many not-so-famous but absolutely riveting personalities of Bombay and Lahore are just a riot to read. I laugh out loud everytime I read them.

LikeLike

If you say Manto’s “Toba Tek Singh” is boring, I would definitely doubt you. And you might have seen the horrors of the Partition but we the younger generations really need, read and love Manto’s description of the Partition.

LikeLike

mr.sheshdri………

i can name u hundred stories of manto without break…which are masterpiece…and yes i hav read almost all the work of manto…sorry for ur poor test.

LikeLike

Thanks sir for all this…..!

LikeLike

Great tribute Shivam sahab :)

LikeLike

Vijay Seshadri: The loss is yours.

LikeLike

I would think that any literary assessment of Manto would be incomplete without reference to his two great contemporaries — Krishan Chander (1914-1977) and Rajinder Singh Bedi (1915-1984). It is not for me to say how Pakistanis — or for that matter, Indians — should “celebrate” Manto but I find this absence a little strange.

At any rate, it is ironic how the three great contemporary short story writers of that generation not only belonged to different religious communities but were also people who wrote in a language that was not their mother tongue. (Krishan Chander and Rajinder Singh Bedi’s mother tongue was Punjabi; Manto was Kashmiri by ancestry but he grew up in the Punjab. It might be interesting to explore why they chose to write in Urdu and not Punjabi.)

Lastly, “celebration” does not mean that we should not discuss Manto’s literary shortcomings. I think that this, too, is a part of “celebration.” And though I would not agree with Mr. Seshadri in his assessment of Manto, even Urdu writers did not feel that he was without flaws. So, in his centenary year let us celebrate Manto: his achievements, his drawbacks, all of him.

LikeLike

I agree with Suresh. The Minto era is incomplete without K Chander and Bedi. I regard ‘Aik Chader….’ as a great Punjabi book. This book was purchased by my father and passed on to me and my children have read from the same copy. I hope to see my G Children read from the same copy. Similarly Krishan’s and Manto’s partition related short stories compliment each other. They were all remarkably free of one sin i.e communalism. We celebrate them all and I am one lucky person to have read them extensively.

LikeLike

Of course, Ismat Chugtai was part of the same generation…apologies for the oversight.

LikeLike

It is nonsense to suggest that Manto is not read. He is read in translation all over the subcontinent. It is exactly the sort of statement a certain type of Indian likes to make nowadays, and their lack of appreciation has less to do with aesthetics or politics than religion. Let us agree to call a spade a spade – in the spirit of Manto (though not with his subtlety)!

LikeLike

Subtlety and Manto? You’ve got to be kidding.

That’s the reason I say nobody actually reads Manto.

LikeLike

Monotosh Ganguly, it is people like you who look at everything through the prism of Religion. Though I proud myself having read a large number of books I have not read any Stories of Manto as I was not aware of his writings and his books were not available in English or in my mother tongue when I used to be an ardent reader.

Have you even heard of books like Thirukkural, Silapathikaram, Manimegalai, etc or even heard of Njanpith award winners, G. Sankara Kurup, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai or SK Pottakkad?.

India is a continent sized country with over 1600 languages and followers of all major religions in the world. So it is impossible for any one to have knowledge about the customs and traditions of every part of the country or the writers in every language.

Btw Saadat Hasan Manto faced recurring obscenity trials in Pakistan and Ismat Chughtai had almost quit writing after “Lihaaf” (or Quilt), I need not recount the reasons for that here.

LikeLike

Well written. Thanks for the effort and a joyful reading.

LikeLike

Thanks for a great introduction to Manto

LikeLike

Isn’t it strange how one whose voice revealed to us the senselessness of hate can himself be an object of hate? Manto’s writings were what made me, as an eighteen-year-old, fancy-schooled girl, feel the pain of loss – of memory, of humanity and of love. The partition was no longer a textbook-confined yesterday, but a live and visceral today. I don’t know what his literary merit is but he did make me cry with just two words – ‘khol do’. In ‘Thanda Ghosht’, ‘Kali Shalwar’, ‘Toba Tek Singh’ and so many others, he urged us to bare and share our collective wounds, across fake borders and false promises. Thank you so much Shivam Vij for this wonderful tribute.

LikeLike

nice!

LikeLike

My gratitude to Beena Sarwar for converting this blog post into an article for The News, Pakistan http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-14-97595-A-hundred-years-of-Manto It’s heartening to see this post has been well received; my debt and gratitude to Manto is very personal. Thanks, everyone.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing the info!

LikeLike

I have read your article “A Hundred Years of Manto” in the newspaper (i.e. The News, Lahore) today on March 14, 2012. It was, no doubt, an excellent article about Manto, briefing such an informative detail about different aspects of his life.

It is really depressing that we provide no value, no importance to our various legendary artists and especially the story writers always have such a miserable ending. People do acknowledge some of the legendry poets; as here is Lahore, the residence of Dr. Allama Muhammad Iqbal has been turned into a museum and it is open for the general public for visits. The house of Faiz Ahmed Faiz is converted into a centre of literary activities and it is popular as “Faiz Ghar”. Various literary activities including mushaira programmes, dastan goi and workshops are conducted in the said house. However, how much importance we are giving to Saadat Hassan Manto? How much we acknowledge the great services of Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi? What have we done in the memories of Ashfaq Ahmed? A number of great legendary writers had no reward, no acknowledgement… neither in their lives, nor even after their death.

Yes, some channels including PTV do play the classic dramas and telefilms based on the short stories of Manto during the days of his birth/ death anniversary but obviously it is not enough to appreciate his great services. Even if we accept the reality that Manto is no more with us now… then what we are giving to the living legends like Intezar Hussain, Bano Qudsia? They all legendary story writers are alive and they are still with us but we have nothing to give them as a reward.

I am one of the biggest fans of various short story/ novel writers… including Deputy Nazir Ahmed, Mirza Hadi Ruswa, Munshi Prem Chand, Krishan Chandar, Saadat Hassan Manto, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Ismat Chughtai, Ghulam Abbas, Rajindar Singh Bedi, Qurrat-ul-Ain Haider, Ashfaq Ahmed, Bano Qudsia, Qudratullah Shahab, Khadija Mastur, A. Hameed, Hajira Masroor, Intezar Hussain… a long list of various great legends who are no doubt the biggest names of literary world. And I feel proud that I was borne and raised in the era when I got the opportunity to meet some of these legends including Intezar Hussain and Ashfaq Ahmed.

I am really thankful to you to share that wonderful article with us, as well as, for all your efforts to compile all the valuable information about Manto. And I personally request you to please do not forget to visit me upon your next tour to Lahore. I am 100% sure that you already have enough knowledge about my city that it is culturally and historically very rich; so, let me have an opportunity to be your host, enabling me to show you the colours of my historical land. I believe you will enjoy your tour with me very much.

Thank you very much once again.

Regards,

Farhan Wilayat Butt

LikeLike

Very nicely put.Thank you!

LikeLike

Two email responses from Pakistan have pointed out a translation error (which isn’t mine, I’m not Urdu literate enough to translate). Here’s an email I got from Riaz Khan:

I read your detailed and moving article on Saadat Hassan Manto which reflects your deep admiration for this great literary genius. It is for this reason that I am taking the liberty to correct a minor error in translation of the replaced epitaph by Manto’s sister which uses the phrase Harf-e-Mukarar (not Muqarar)on Loh-e-Jahan. The translation, in my view, should be ” Here lies buried Saadat Hasan Manto who still believes that he did not have a parallel on the face of the earth.” The phrase, as you know, is from a well known verse of Ghalib: ‘Ya Rab! Zamana Mujh ko Mitata hey Kis Liye. Loh-e-Jahan pe Harf-e-Mukarar Nahin Hoon Mein’. This can loosely be translated as: ‘God why is time destroying me. I am not (like) a repetition (or repeated word) on the template of the Universe’. It is an allusion to the practice of rubbing off a word that is mistakenly repeated while writing. Harf-e-Mukarar is “repeated word” and not “final word”

LikeLike

Above post is informative . Feel so wonderful after reading ur post

LikeLike

Many many thanks for this amazingly useful nice post!

LikeLike

On Monday 11 May in Delhi, a play on Manto’s life and times – http://www.facebook.com/events/346581705396564/

LikeLike

Dafa-292 A play by NSD Repertory Co. is based on the life and works of famous story teller Saadat Hasan Manto is going on in SAMMUKH Auditorium ,NSD Campus till 4th of nov. at 6:30 plz b there…music,design nd direction -Anoop Trevedi

LikeLike

Reblogged this on follae.

LikeLike

VERY NICE BLOG, IS THERE ANY ARTICLE ON -MANTO KI MOKALMA NIGARI- Plz send on naushadmomin@rediffmail.com.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Neat Shots of Life.

LikeLike

Mr. Seshadri…

1. Manto is not meant to be

funny. Ever heard of DARK

HUMOR?

2. If you can not find the subtlety

in Manto’s works, you need to

go and learn to read literature

again.

3. If you say that Manto is over

rated, I think you need to

acquaint yourself with the fiction

being written presently by many

writers and I don’t even need to

take names here.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on A datapost’s Blog and commented:

Saadat Hasan will die one day, but Manto will live on.

– Saadat Hasam Manto

“India was free. Pakistan was free from the moment of its birth, but in both states, man’s enslavement continued: by prejudice, by religious fanaticism, by savagery.”

– Saadat Hasam Manto

LikeLike