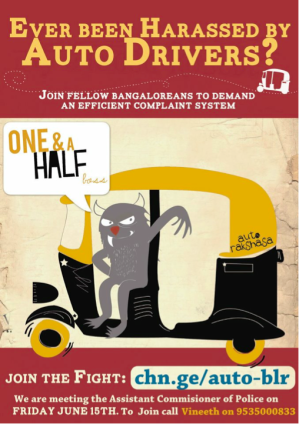

A petition from an organization called Change India invaded my Facebook wall today right before – rather ironically, it turns out— my morning auto ride. The petition is filed under a category on the site called “petitions for economic justice.” When you open it, the image pasted below opens. A sharp fanged, dark skinned “auto-rakshasa” demands one-and-a-half fare. The commuter is “harassed.” The petition that accompanies this image urges the ACP of police to create “an efficient system” so that complaints made to report auto-drivers who overcharge or refuse to ply can be tracked. How, it asks, can “concerned Bangalorean citizens” expect “justice” if their complaints are not tracked? We all must, it urges, “join the fight.”

Let me first say quite clearly that I do not mean to undermine the intentions and frustrations of those who launched this campaign and, yes, when the meter goes on without asking, it eases a morning commute significantly. The question is: if this does not happen at times (and indeed it doesn’t) then why is this so and what does one do about it? There is a lot to be said about the economics of the issue itself and I welcome others reading who know more to write about it more extensively. But this piece is not about that. It is about the campaign itself and how we articulate political questions in our cities. It is fundamentally about the easy, unremarked way in which a working urban resident and citizen – who is also, after all, a “fellow Bangalorean” and concerned with “economic justice”– can be termed and portrayed a “rakshasa” as if it were a banal utterance.

Our urban institutions don’t, in many ways, work. We know this, the poor have always known it and it seems to be the newly discovered ire of elite politics. We complain, the petition says, and “no action” is taken. This complaint is not unique to this campaign or to the elite. The narrative commonly told about our cities today is in terms of “failure” and “illegality” whether it is dysfunctional institutions, corruption, broken infrastructure or slums. I am not contesting these failures or the anger of the petition writers at it. There is, however, a “but.” It is, put bluntly, this: not all institutional failures are the same, not all crimes are equal and not all illegalities lead to the same consequences. Protesting against them without taking this into account is not just ineffective, it is deeply unjust. Let me take an example from housing. Rich people who build illegal houses make “farmhouses” and “unauthorized colonies.” Poor people who do the same make “slums.” In a campaign against “illegality,” only one of them gets demolished. Only one is called an “encroacher” and a “pickpocket.” Only one of them can be a “rakshasa,” the other gets to be a “citizen.”

But, the campaign writers may rightly say: “We are not against autodrivers – it is about complaining against those that overcharge.” Does then a campaign’s representation, these words, this cartoon (ahem) really matter that much? It does. These imaginations, names, words and aesthetics alter, narrow and limit urban politics. You cannot see a rakshasa as another citizen who lives in your city. There was an alternate way to run this campaign: to sit with associations and unions of auto-drivers and come to an agreement. To find out if auto fares are reasonable, high or low. To figure out community mechanisms to prevent non-metred travel. To, if that’s what came out of the engagement, support campaigns for metre fare increases as inflation, prices and petrol/gas increase. To work out a periodic shock-absorption surcharge for periods with very high gas prices. To find out why it costs four times as much to own and register an auto than a Tata Nano. To find out what the daily rental of the auto-driver is that he is trying to make in his twelve hour shift. To figure out why his fares are regulated though the rental he pays isn’t. To consider, quite simply, the auto-driver as a person and a citizen rather than a criminal or a rakshasa. To find out how the institutions the petition is angry at have failed him just as much and, most likely, with much deeper consequences.

Instead this campaign pits “concerned citizens” against “autodrivers” that are, as the image suggests, always already criminal. It repeats the mistake of multiple recent middle-class campaigns for “economic justice” and “social change.” These campaigns increasingly target a particular set of issues –for example, corruption or security – that should concern all of us but because of the way they are defined and articulated instead exclude what is a majority of our urban citizens.

Where do such images come from? Let me trace just one possible thread. In another context, Leela Fernandes has argued that Indian cities are defined by a “new urban aesthetic of class purity.” She was referring to new forms of elite built environments from streets cleared of the poor, gated communities and enclosed malls, and parks where one can walk and play but not sleep and work. Yet this aesthetic doesn’t just manifest itself in the built environment – it is part of an elite urban politics that cannot imagine the poor as fellow citizens. Elite and middle-class campaigns thus become something altered– they are reduced to the protection of what Fernandes calls a “lifestyle.” Not the Right to Life, but the Right to Lifestyle. In the protection of this lifestyle, the working poor cannot exist as fellow citizens with rights and dignities. Their concerns cannot be part of the conversation. They are “rakshasas” that take resources from the state, are the sole reason for public debt, encroach on public land, burden athe government for “handouts,” and pollute and dirty the city just as they take hard-earned tax money taken away from its rightful heirs.

The responses that these campaigns seek can understand “economic justice” only in the form of punitive and disciplinary punishment for the always already criminal poor. In this particular campaign, the only possible result is a deeper surveillance and harassment of auto-drivers by law enforcement – no other interaction is possible, no other solution is conceived. Herein lies the tragedy. What is this campaign fundamentally meant to be about? It is about what happens to a complaint made to a public institution about a service. It could relate then to other, larger campaigns about getting public institutions to work and be accountable to all parts of what makes our urban public. The autodriver is as interested in this question as you or I yet he is excluded, in this frame, from asking it. Worse, he is held responsible for it.

Make no mistake: many campaigns of and by the poor often make the same mistake. They often demonise, for example, all things shorthanded as “private” or anyone that touches it with a ten-foot pole. All things “private” are often the rakshasa in the room so that possibilities where private provision could be more egalitarian than public provision become foreclosed even before they are considered. They forget that “private” also means small scale enterprises, informal associations, and even unions – not just mega-conglomerates. That’s what raksahas of all kinds, colours and shapes do: they draw lines of fire that we cannot cross either in our minds or our politics.

At stake then are our increasingly polarized urban polities and the movements and campaigns that emerge from them and abound with rakshasas. Yet what other forms, discourses and aesthetics of politics is possible? I have no easy answers for this. It cannot just be a new set of semantics and images – structures of tremendous power maintain and reproduce the inequality that makes this image possible and tragically ordinary. Finding a political space and language that can cross entrenched inequalities is perhaps an impossible end that we are doomed to nevertheless chase. The challenge before us is to understand how the possibility of asking interconnected, larger questions that truly reflect the complexity of our “public” can emerge even if they take, at first, simply an act of protest like these words against the reduction of a fellow citizen to a rakshasa.

But it in no way condones the sins of overcharging and misbehaviour. It must be understood that most of those who ply in these autorickshaws are not the ones who build illegal farmhouses or CEO of industrial hubs or the top 1%. They are common citizens, typical middle classs who also have churned in to make it to a comfortable job that makes them afford an auto rickshaw. If everything is left to whims and wishes of everyone, there would be chaos and utter rule of lawlessness. What is now being demanded is a common problem and it needs to be addressed pursue. Not withstanding the demonization of these poor autorickshahwallas, it could be done in a better way, rather generalizing every auto wallah as auto rakshas. Much better could be done, if the commuter could take note of the auto numbers of those who misbehave and and govt initiates a grieviance reddress mechanism that can address the customers complaints faster and readily.

LikeLike

Excellent piece but would like to have the full Leela Fernandes reference.

LikeLike

Pardon my low IQ (or my lack of comprehension skills), but I don’t understand what exactly your post is against.

1. Is it against using the word “rakshasa”? If so, I think it is just wordplay (sounds like rickshaw), and is trivial and inconsequential.

2. Is it against the campaign itself, because you think it is some kind of elitist, upper and middle class aggression against the poor?

3. Is it about campaigns, in general, that unconsciously, subliminally, exclude certain sections of society?

Pray deconstruct.

LikeLike

ABC,

I will only reply to the first point you make.

The ‘wordplay’ you refer to is not trivial. And it is most definitely not inconsequential. The ‘rakshasa’ imagery is one that has been used to subjugate, humiliate and marginalise, at different stages in history and fiction, indigenous people, people who aren’t upper-caste and most recently, the working classes.

The rakshasa rhetoric posits the Aryans (or upper castes or upper classes) as a complete antithesis to the rakshasa.

This Aryan-Rakshasa paradigm is extremely problematic, and it’s not difficult to see why.

The language we use is crucial, for many reasons. Such kind of systemic and systematic internalisation is, I assure you, anything but trivial.

LikeLike

Stuti,

I think, in the poster, the word rakshasa means someone who acts like a villain. I think the word found its way here because it sounds like rickshaw. Hence I still think it’s wordplay. About the effect it has on readers, you can’t really do much to prevent their straying down the bigoted path, since they are inherently bigoted and will interpret anything as being supportive of their view. I do not think the word rakshasa here alludes to the whole Aryan-Rakshasa mythological divide and such. Let’s not impose our interpretations on something that is essentially just wordplay.

LikeLike

Something on similar lines… about delhi auto drivers.

http://bigeyedfish.wordpress.com/2012/06/07/automatic-for-the-people/

LikeLike

Instead of getting all angsty about the poster, why cant you see the campaign as only against the auto drivers who harass and not against auto drivers in general?

And all your high sounding class purity fundas don’t really apply here. People who live in gated communities drive cars. For your information, autos are used by the poor and the lower middle classes as well. (Ever heard of the term “share auto”?)

Suggest you try removing your “class warfare goggles” before you decide to complain about campaigns the next time.

LikeLike

Has the author ever tried hiring an autorickshaw in any city of India? Barring Mumbai, autorickshaws (and taxis) everywhere in the country are run like a free-for-all mafia. It is only on an exception that a ride in on the “meter”. In Bangalore, it is almost never on the meter. EVen in Mumbai, which used to be different, the picture has deteriorated rapidly.

The reason is simple – established mafias (and politicians, not necessarily distinguishable from each other) masquerading as unions run the taxi/auto fleets in our cities. And they scuttle every move towards having a modern system. EVery modern city in Asia – Singapore, Hong Kong, KL, Shanghai, even Jakarta now – have fleet companies operating cabs in the city. It makes regulation easier, and the consumer experience uniform. In India, the existing union mafias scuttle such initiatives.

It oh so “left liberal” to infuse a class element to what is considered a basic civic right in every civilised city in the world. There is no class element to a harried lower middle class mum trying to flag down an auto to bring her kids back from school while the school bus union has gone on strike (without notice). And finding that no auto is willing to travel such a “short distance”, and even those that do, insist on getting paid a 2X amount.

“sit down and talk to the unions”! Hilarious. In Mumbai, talk to whom? Chaps like Quadros, who brings up the front of the rent seeking infrastructure profiting out of the broken cab system? A guy who runs a fleet of cabs himself, and any institutionalisation of the setup sends him straight back to the boondocks! Is he amenable to change? The Maharashtra government took these jokers on a fully paid trip to Singapore a few years ago to see how the system can work. They merrily went there, enjoyed the Lion city, and came back and went back to business as usual.

The monsoons are nearly on us. It would be an interesting experience for Gautam Bhan to try hiring a cab from Bandra station to go the Mumbai Uni campus in Kalina. Maybe he should do that, the “class elements” will vanish quite rapidly.

LikeLike

…hardens attitudes, promotes meanness that seeks to haggle down say metered fare, prices of vegetables/fruits, evicts slums, brutally recovers debt (‘you dont know these people’…)

we must assume a toughness that is emblematic of a lifestyle of unending accumulation…(‘a penny s(h)aved is a penny earned’)…a universalist ethic compatible with indigeneity

(thanks Gautam Bhan)

LikeLike

very interesting read. your post is particularly relevant and well located given the auto-driver motif of the kafila header. it is, as you rightly remark, unjust for the urban discontented to target the category of the auto-driver.

i think dealing with the categories of the ‘poor’ and the ‘rich’ also undercuts, in some sense, an inclusive understanding of citizenship.

LikeLike

As someone who visits B’lore at least once a month I know how auto drivers fleece customers.I often end up paying more than 1.5 times of what the driver should charge as per meter.So I understand why some persons are so angry and upset with them.But I do not think that the solution as sought by them is a preferable one.I am not convinced by Leela Fernandes’s argument. It is true that there are gated communities, malls and these are expressions of consumerism and preference for amenities. Malls are open for all although not all those who visit them can afford to do shopping there.The real threat for the poor is not from these upper middle class or the new elite but from those who enable misappropriation of public resources for private gain. Those who buy flats often do that by taking long-term loans and other commitments. But how many schemes are there for the urban poor to own their flats. Is not the state supposed to help them in this. Today it is politically correct to blame the upper middle class particularly those employed in MNCs and IT industry and castigate them as insensitive elites.

LikeLike

Dear all,

The assumption that I have never had to ride, let alone haggle with an auto, is quite amusing to me. I live between Delhi and Bangalore, and my daily commute in both cities is entirely on public transport split between autos, metros and buses. So I know the “issue” is real — the entire point of my piece was to talk about how it is raised not to say that it shouldn’t be. All benefit of the doubt given for a moment to the petitioners, I am arguing precisely that well-intentioned campaigns can become deeply exclusionary because they emerge from power structures that we both consciously and unconsciously occupy and reproduce. To ignore our privilege and power is not a choice any of us must be allowed to make. You may say “Rakshasa” is just a word, ABC and Nookayaa, but in using it, this is no longer a campaign that is just about some autodrivers who harass. To me, it isn’t — its other effects are too powerful and too apparent and too rooted in a prevailing climate in our cities where the poor are, at best, annoyances that get in the way of our GDP or, at worst, criminal. The ten-fold increase in slum evictions across our cities in the last decades isn’t a coincidence — its imaginations, words, and images like these that make it possible. A rakshasa’s home is just not worth the same as a middle-class residence, what difference does its eviction matter?

Somnath, I am well aware of the problems with some of the auto unions — hence I wish that autodrivers had other spaces and sites to find solutions to their own concerns as well. Will campaigns like these ever make that possible?

I will say one more thing: there is, today, an increasing tendency for those in the “middle”, “upper middle” etc to (it seems to me) genuinely believe that they are the true victims in our society. This narrative of victimhood easily absolves us of the true nature and extent of inequality in our cities and seems to allow us to take no responsibility for either its existence or its reproduction. You will accuse me now of saying that poverty is not an excuse for illegality — this is true but neither is wealth but the latter pays little or no consequences. When systems of justice (including complaint redressal) work punitively and selectively, they are not just. Calling upon them to exercise more power ignoring that is, again, neither effective nor just and it is, without a doubt, an act of power from those of us who can wield it.

Mohan: The reference is a journal article from Urban Studies in 2004, I think, called the Politics of Forgetting.

best,

Gautam

LikeLike

It’s distressing and amusing sometimes, to note, that earlier debates on this issue seem to have totally bypassed some readers. Please refer to Simon Harding’s posts on Delhi autos on Kafila. Harding’s is no knee-jerk reaction either, it is based on a longer study he did with a colleague over several months. I also interviewed the demonised auto drivers of Delhi in 2003-04 for a paper, which was on the same lines as Harding’s study. The point that Gautam is making really is not about letting auto drivers off the hook or not. It’s about knowing more about the conditions they work under; conditions that most of us may not ever have to see in our lifetimes. It is about auto-walas getting squeezed between rising costs (fuel, daily necessities, spare parts, CNG in the case of Delhi) and a powerful bureaucrat-police-financier nexus that only allows those with muscle or money to survive the brutally competitive auto driving market. It is about the hidden costs drivers pay, that can never be publicised because they are in the form of bribes and arbitrary fines. It is further about selective citizen activism, wherein organisations like the one in Bangalore, and People’s Action in Delhi target auto drivers by using emotive language that refers to the daily suffering of middle class consumers (Somnath, here your image of the mother and her school going kids is a masterstroke). For instance, it is interesting that bus users’ issues never get so much publicity, even though many of their woes are even more intractable. It is also amazing that with no middle class campaign has yet targeted say, illegal farmhouses, or encroachments. On the contrary, the sealing exercise in Delhi which targeted businessmen received the ire of the middle classes. It is very much the fact that autorickshaws are the only interface that the relatively cushioned classes of this country have with public transport (barring the Delhi Metro in recent years) that pumps up the visibility of these campaigns. Not that it automatically disqualifies such a campaign. But we’re speaking here of the partiality of a vision which assumes that reasonable fares and behaviour from auto drivers would be necessarily a legal, sustainable arrangement for auto drivers too. Given the extortionate auto licensing lobby in all cities, wherein as Gautam pointed out, autos cost four times as much as a Nano, this is currently impossible. If they don’t squeeze the consumers, they don’t survive. A campaign should then logically target the real culprits – but this is much harder than simply demonising the auto drivers.

LikeLike

Sunalini,

“For instance, it is interesting that bus users’ issues never get so much publicity, even though many of their woes are even more intractable.”

The campaign against red line buses in the ’90s? The campaign over the quality of DTC services? The current modern bus fleet in Delhi is the result of sustained campaigns against the poor quality over many years.

“the sealing exercise in Delhi which targeted businessmen received the ire of the middle classes.”

On the contrary, it was the much reviled middle class that sponsored the entire campaign against mixed use real estate in Delhi. When the sealing started, the tenor of the critique wasnt too different from Gautam’s and yours against the auto campaign.

LikeLike

Hello? In the nineties, the middle classes were still forced to use buses, the car ‘revolution’ not having taken place yet. I was talking about right now. And please specify which middle class actually turned against mixed land use. In the sealing case, a small but vocal group of bourgeois environmentalists were up against petty shopkeepers and businessmen. On the whole, businessmen received much more sympathy from the media than those whose slums were demolished in the enforcement of the Master Plan in Delhi; the latter vanishing almost overnight, as Gautam’s book painstakingly records. The point about selective and class-determined citizens activism remains.

LikeLike

If the problem is rent seeking by auto licensing lobby, then paying a higher fare signals the auto licensing lobby to increase their rent. The more you pay to the autowallah, the more money will be extracted by the auto licensing lobby.

LikeLike

Correct. So who should the campaign target?

LikeLike

Gautam,

Unfortunately the “platforms”, or solutions will be and are derided as elitist too! As I mentioned before, most civilised cities in Asia have their cab fleets run by institutionalised operators today. Attempts to do that have met with fierce resistance, not least from the “oh so liberalati” in every city in India.

In absence of policy responses therefore, the consumer is left with no other option but to use the existing instrumentalities of the state. With a corrupt state apparatus obviating any meaningful intervention, the only visible mode of redressal is the sort of campaigns that you referred to. These campaigns build pressure on the state, howsoever temporary to act.

If you deride these initiatives as “elitist”, you push the middle class (the “lower” middle class mind you, which is the predominant user of autos) straight into the arms of the likes of Raj Thakrey, whose MNS reacted to the auto menace earlier this year by simply burning down a few autos. Believe me, for a mum trying to flag down an auto in pouring rain to fetch her kids from school, and being refused everytime, the MNS option doesnt seem unfair at all.

The “rakshasha” campaign is a much better vent, much much better. Leela Fernandes notwithstanding. (BTW, which civilised city allows its parks to be used for “working”?)

LikeLike

What does this statement mean that a “civilized city ” would not allow its park for “working” ? By working, I presume the author means things like a vendor selling his wares. What is wrong with that ? It shows initiative, hard work, productivity.

I have lived in New Delhi, London, New York, San Francisco and what I love about India is its Freedom. People can walk, eat, run, swim, bike, sell etc where they want. In the West, every corner has four rule boards placed. You cannot run a society based on rules – it has to be based on relationships within a broad framework of rules about right and wrong. In India, the balance of the system is based on a healthy balance of macro laws and micro human adjustment whereas in the West, every micro human act is regulated and licensed. This leads to laws being prioritized over justice, legality over actual right and wrong.

In India, we have till now been able to say ok, this is the law but what is right here ? This is the point Gautam is trying to make: Why target a poor citizen ? Why demonize the auto-rickshaw guy for breaking an unworkable law instead of finding out what is wrong with the system and campaigning for reform ? If you whine about corruption etc and therefore, that “it will be no use” – well, you have given up before you tried. And it doesn’t make it right to do something wrong just because it is the easiest thing to do.

The Indian middle-class elite are being pushed into the same consumerist-selfish-victim-mentality-bread-and-circus hellhole that I saw the corporate West push its own people through regulatory and media capture, which leads to among other things the class divide and a complete loss of the ability to objectively see what is “right” and have the courage to follow it. It also leads to unhappiness, inability to develop relationships or achieve anything, over-dependence on what others think, inability to think for oneself and needing an authoritarian rule or law etc but that is grist for another mill.

LikeLike

It’s no wonder that the autorickshaw is the darling of the Indian Leftist intellectuals – it is the perfect symbol of socialist India. Completely under government’s central planning control – through license-permit raj at entry and fare control during operation, slow enough to slow down everybody else (thus ensuring ‘equality’ – middle finger to those uppity carwallahs!) and of course, ‘pro-poor’. Like any central planning solution, the autorickshaw has been immensely enriching to the bureaucracy (and the unions). As has been pointed out (ironically by leftists themselves) multiple times, the autorickshaw owners are investing precious capital not in any physical assets that will improve their services to their customers (and thus earn them more revenue), but in mere paper. I can bet that the Left’s solution to the problem, like everything else, will further enrich the bureaucracy. But why blame the Left, Indians in general love any solution that will expand the government’s waistline – hence MGNREGA, ‘right to food’, ‘right to education’ etc.

Will the intellectuals that run around ‘studying’ suggest the obvious solutions as well – decontrol city transport completely, not just licensing, but fare control as well (the latter exists in faded ink on paper only anyway, but has been a source of steady income for the enforcers)? When will the intellectuals learn that ‘regulation’ always hits the small guy much, much harder than the big fish, even though the supposed aim is to stick it up to the latter?

LikeLike

While reading some of the replies here, i was reminded me of what P. Sainath once wrote, quoting a farmer, in a different context: “What the heart does not feel, the eye can never see.”

(refer http://www.hindu.com/2006/09/08/stories/2006090806591000.htm)

LikeLike

It is not surprising that the middle class “elite” is protesting against the auto rickshaw drivers in Bangalore. After all, they are affected by it directly. It is too hard to make fundamental changes that are the root causes of ANY public ill. Corruption? Poor clerk had to pay lakhs to get his job. Bad doctors? They had to spend millions to get their degree. Poor auto drivers? Others have done a better of explaining their behavior. Does it mean, every time we try to address an issue, we should take on the whole society and fight for justice. In an ideal world, yes, but in reality it is impossible for anyone take on such a task.

I am not against addressing the root causes. Let the leftist intellectuals come forward and provide leadership for such movements. It would be wonderful to have a totally just society.

I have had a mixed experience with auto drivers in Bangalore and Hubli. From a very sympathetic driver who helped get an injured person to a hospital without payment, to a driver who deliberately made me lose my bag with laptop and passport, to a driver who sang perfect carnatic songs while driving and everything in between. I wouldn’t caricature them as rakshasas, but just because someone used that term does not make it illegitimate. Power to the facebook andolan!

LikeLike

using the word rakshasa to denote an entire class is irresponsible in the extreme. like you said, some of them are very helpful. this campaign creates a class divide. nothing which creates a divide can create a solution. you have to live with these people. do you want to force them through laws to do exactly as you please whatever the economic and mafia pressures on them ? then you will only complain about how inhuman these people have become and no auto driver will take an injured person to the hospital because there is no “law” that says they should and they are angry at the world which forces them to bear the brunt of an unfair system.

instead, the better option is to treat them like human beings and ask the government to find a solution for both the driver and the rider. the campaign should be focused on the government and pressurizing it to find a solution, not the rickshaw driver – i assure you they are not socking away the extra money to fund their swiss bank accounts or buy a farmhouse for the weekends.

LikeLike

Sfire,

I agree with you in principle. It is counterproductive to demonize any group of people. Perhaps it is excessive to call them Auto rakshasa. But the problem still remains, and shouldn’t we focus more of our energy on finding solutions rather than shooting the messenger who used a politically incorrect or perhaps even an insulting term?

-RK

LikeLike

By the way, very well written piece Gautam!

LikeLike

As the designer of the poster: Here’s a response to this post http://bonifisheii.blogspot.in/2012/06/gods-and-demons.html

Thanks

Shilo Shiv Suleman

LikeLike

Dear Shilo,

Thanks for the reponse and for writing. You know, I live with a graphic designer and he taught me one critical thing about images: if you have to explain what your image means, then it isn’t working quite the way you think it is. I understand that when you place that image against the other rakshasa characters (I really like the idea of the “inner rakshasa” in all of us, by the way, in which case the image is playing a totally different role) then it has a totally different life. But this image of this auto-rakshasa appears to me as someone who sees it independently as part of a campaign that travels far beyond the context in which you created it and it then must be judged on its own. I stand by my reaction to it and you don’t have to agree with my reading but I hope that you will consider it as a reaction that many have had to it. You may feel it is a misreading of your work but all our work — your illustrations and my writing — travel beyond our intentions. The image in question was used in a public campaign and so, as someone receiving it, my reception of it is actually independent of your intention in creating it. It’s the old rule of impact over intent. I hope you consider that when you see how your work is used. Whether it was meant to be serious, ironical, satirical or humorous is perhaps no longer the question when images associate with political campaigns and travel far and wide.

I will disagree, respectfully, with your idea of something just being a “cartoon” and thus somehow devoid of serious impact. I think in this moment, particularly, there hardly needs an explanation of the power of cartoons and images. And as for “rakshasa” being just a word-play, I’ll say again that I think we owe it to ourselves to see take the power of words and images seriously and recognize that “harmless” images can offend, exclude and exercise power. The Ambedkar cartoon controversy is ample proof. I have worked for many years on issues of slum evictions and I have seen similar images that have led to the devaluation of far too many lives. I know you think these are unrelated extrapolations from your single image but I am hoping to draw your and others attention to how we are implicated in larger structures of power that do not need us to actively and consciously exercise them for them to be real. You can make of that, of course, what you will.

Best,

Gautam

LikeLike

i think drawing a comparison to ambedkar cartoon over here is a bit problematic. Unlike this poster which was meant to travel far and wide on its own as part of a compaign , the cartoon was embedded within a text which did not either endorse or criticise it, but used it to contextualise a historical moment , while overall critiquing the critique of the process of something momentous like drawing a constitution . Since this poster was meant for an individual compaign , the poster itself should have clarified that it was talking

about the inner rakshasa in all of us and put it alongwith other rakshasa images there itself ( just like the textbook was full of other cartoons) , for as a standalone post in a compaign meant to spread far and wide, it is very clearly liable to be read the way Gautam has read it .

In a culture where visual representation can be powerful in its impact, either as reinforcing dominant power or as a tool of subversion and a range of things in between given complex intersectionalities , one cannot but be cautious in drawing comparisons . Debate and disagreement there must be, but the dangers of a culture of imposition of blanket bans and censorship underline the need to contextualise our critiques and differentiate their nature adequately. So also the need to differentiate between different controversies in a critical engagement.

LikeLike

Besides even in the absence of adequate contextualisation, the ambedkar cartoon did not so easily and unambigously lend itself to any clearly offensive reading towards a particular community, as this cartoon does in ABSENCE of proper contextualisation and representation within the poster itself . When you use mythology and attempt to express complex ideas like ‘inner rakshasas’ you have to be even more careful that the complexity of the meaning gets across in a reasonably unambigous way.

LikeLike

I think it’s a good example of why creative people need to unpack their statements for messages that they may not have intended but are implied due to cultural baggage. I once fought with an auto driver over an extortionate fare and complained about how ‘you people’ always rip passengers of. He took especial umbrage at that, thinking ‘you people’ referred to his community. He was right to be on the defensive about that kind of attack, and I was wrong not to think my words through better. The fact that he was ripping me off doesn’t change this.

LikeLike

I find it amusing that there are people here attacking auto rickshaw drivers as criminals for “overcharging” etc. Yet many of those same people defend the “free market.” When meter rates are not revised for four or five years (I think it’s been at least four years in Delhi) while auto rickshaw rents, overall costs and living expenses have been rising by leaps and bounds, what exactly do you expect drivers to do? Frankly, I am not willing to endorse even the caveats Gautam Bhan has put in about “illegality” – this is not a crime at all. One can never endorse a campaign against it. It is a “free market” negotiation, of the kind so beloved of our elites, and like all such “free markets” it is built around power, where the auto driver is exploited by a powerful nexus of interests and in turn exploits whatever little market power he (never she, sadly) may enjoy from the momentary monopoly of your transport options (rarely ever a real monopoly). The same rakshasas derided by Somnath as exploiting a “lower middle class mother” also include many who give free rides to injured accident victims or the sick. All of this, again, is a sign of a “free market” in operation – you have no idea what you’ll get. Sorry, people, you want options to travel cheaply, use public transport, and meanwhile let us work towards collective solutions that work for all. Campaigning against auto rickshaws overcharging is not only not a high priority target – it should not be any target at all.

LikeLike

If there was real free market in this country then there would not be a limit on the number of autos that could ply on the road. That in turn would have taken care of the issue of over-charging by autos because competition for customers among auto drivers would have ensured a fair price since it would be based on the laws of demand and supply. This kind of illegal over-charging happens when supply is curbed artificially (you do know there is a limit on the number of autos that can get licenses in Delhi)! Why else do autos in Bombay go by meter and do not over-charge? This is basic economics 101 which obviously most haters of “free market” don’t understand.

LikeLike

It is not basic economics unfortunately. There is no market where price cartels dont operate – the myth of the ‘perfectly competitive market where price is automatically at lowest average cost’ due to ‘free interaction of demand and supply’ is a mirage which does not exist anywhere in the world ( not even in basic agriculture as textbooks proclaim). Most prices you pay for most goods and services involves rent seeking by firms under the maxim of profit maximisation and product differentiation in oligopolistic and monoplistic markets, just notice how the price for a simple cup of tea can vary from place to place – dhabas to malls to resorts . There are often very powerful barriers to entry and exit that these very firms create against entry of new firms to prevent prices from falling and the excess rents they earn dissapear. The only difference is in case of economically weaker sections like ‘autowallahs’ , you can cry foul and ask for legal and state intervention to secure when the market doesnt operate according to your own sweet desires. You cant force corporates to the same in their pricing policies – whatever they charge – and however unethical the practices in charging prices .

LikeLike

The bogey of “free market” is economically moot in this case. Public transport of all types are natural monopolies. Which is why they are operated by publicly owned and/or publicly regulated utilities. In the case of autos/cabs in Indian cities, instead of regulating a limited number of operating utilities, the field is left open for politicians for rampant rent seeking through licenses.

Any attempt to bring about a more modern system is wrecked by the same vested interests, cheer led in no small measure by the liberalati in our metros.

LikeLike

As rohan has very accurately put it earlier – it is not only public transport, but all forms of economic activity, where the “free market” is a mirage. Free markets in the neoclassical sense do not exist and never have. In order to get around this basic fact, neoclassicals invent a whole range of other theoretical constructs, such as “information asymmetry”, “externalities”, “market failure”, “instiutional economics”, etc. in order to evade the basic question of power over production – much like Ptolemy invented a whole range of astronomical fictions, epicycles and the like, to get around the fact that the universe does not orbit the earth. As such, even if there were a “limited number of operating utilities”, the same exploitative situation would prevail – though the exploitation may shift to the drivers entirely. Incidentally, there are indeed a limited number of auto owners – most drivers do not own their vehicles, and some owners own entire fleets. In this sense what is the difference between the situation you envision and the present one?

LikeLike

From his writings here, I gather that somnath is pro-market and pro-liberalization. That he too believes in the myth of natural monopoly is instructive – socialist education is full bang for the buck. There is no such thing as ‘natural’ monopoly – it is a myth invented by statists to justify their interventionist policies. Please take a look at this paper: mises.org/journals/rae/pdf/RAE9_2_3.pdf

Excerpt: It is a myth that natural monopoly theory was developed first by

economists, and then used by legislators to “justify” franchise monop-

olies. The truth is that the monopolies were created decades before the

theory was formalized by intervention-minded economists, who then

used the theory as an ex post rationale for government intervention. At

the time when the first government franchise monopolies were being

granted, the large majority of economists understood that large-scale,

capital intensive production did not lead to monopoly, but was an ab-

solutely desirable aspect of the competitive process.

ShankarG: the free market never existed (not entirely true, but that is another story) precisely because the interventionists never wanted it to exist in the first place. Wherever their gaze was diverted for brief periods of time, not only did the free market exist, but thrived as well. Until the interventionists discovered.

LikeLike

Wow, lack of economics education in India is on full display here, in the comments of rohan, shankarg, & somnath. Having such a weak grasp of economic concepts is disturbing.

LikeLike

@JPallipad ,Wow- why dont you enlighten us poor indians, Mr High Preist of the sacred profession who understands this enlightened science? I’m sure that would be worth a little more than a snide derogatory remark which displays your own ignorance,an absence of any argument and a deeply supercilious patronisation which is thoroughly condescending ? I find it more disturbing that even in this age , when economics as a discipline itself is facing such deep crisis about its own understnding, its high priests still retain the empty arrogance that they know better .

LikeLike

The facebook group is doing what they can. Will Sunalini and gautam and their ilk do more than armchair critiquing. can they organize workshops on how they can deal with their lives and profession better? Do it – dont just give sermons on kafila to people who are trying to do what the can – if you can do better, do it.

Yes, my sympathies are with the auto drivers – they are not necessarily well-educated or able to benefit from other opportunities. But, does that not mean they can extort people.

My simple way of dealing with them is not to entertain extortions but to rather incentivise those drivers who readily take me to the destination I want to go to and who do not ask for “extra fare” – I tip them a small amount (<5%) and tell them why I am giving that in the hope that the message spreads and they provide better service. More people doing the same might actually spread the message. I know all commuters may not have the ability or the propensity to tip but many of them can. The danger of tipping can also be that it becomes part of the "normal" and things dont change – but it atleast shows that we care about the drivers, and carrot is a better policy than stick.

LikeLike

this is the most beautiful and well-argued piece that i have read in the entire day. kudos!

LikeLike

Thank you, Gautam, for a very well written and well considered piece. I fully agree that double standards are applied in the urban Indian context when it comes to illegality. Perhaps there is more of an understanding amongst the elites as to why someone might build illegally, given their experience of the bureaucratic paperchase that ensues whenever such activities are pursued. Maybe it does not inspire such rage as it is not seen as impacting upon anyone’s everyday life. Conversely, there seems to be a lack of awareness of the urban informal economy and its equally perplexing illegalities, semi-legalities and injustices. This paucity of knowledge manifests itself in a desire to crack down hard on autodrivers/taxi drivers etc. with technical and legalistic instruments which would hold drivers in a vice with the campaigning passenger on one side and the state, financiers, contractors and the traffic police on the other. The latter group, despite being the cause of overcharging, get away scot free due to the lack of knowledge mentioned above.

Your discussion of the work of Leela Fernandes is also interesting. In relation to the auto-rickshaw, comments made by various members of the Delhi Government in recent years claiming that the auto has no place in a “world class city” resonate with these ideas. The DG would extend the “class purity” of the gated communities, malls and markets to the roads.

This campaign mirrors a similar one against tax drivers in Calcutta. Again, an attempt to hit the drivers hard with little understanding of why they act as they do in the first place. As with this campaign, the “why” is missing.

LikeLike

i guess gautam bhan is talking about the problem and limitation of the nature of campaign. if the structure of the campaign gemeralises and demonises every single auto-drivers, then negotiation will be negated, only a coercive approach will get perpetuated and that is dangerous. this is what the article says if i got it right.

LikeLike

As a woman who has lived in Calcutta, Mumbai and Bangalore and have used autorickshaws extensively, I wholeheartedly support this initiative in Bangalore, because the city is in desperate need of it. And as far as labelling them as ‘rakshasas’ goes, you can hardly blame me, because I have been physically assaulted by auto drivers on two occasions in Bangalore after I protested against extra charge demanded by them. And I would also like to specify that both these incidents happened at 4 pm at busy intersections of the city while the police looked away. And this is the story of not just me but also other girl friends who find themselves travelling alone without a male escort. And it’s hardly a surprise that FIRs and complaints go unattended or dismissed outright as close to 70% of the autorickshaws in Bangalore are owned by the police constables themselves.

Even though I admire your intentions in writing this article, having had first-hand experience of what these auto drivers are capable of and proceed to do on a regular basis, the campaign is spot-on in identifying and naming these criminals as ‘rakshas’. So your utopian suggestion of ‘discussions and talks’ does not apply to the lawlessness that is Bangalore.

LikeLike

thanks for this gautam. well written and well argued. this demonisation is true for the kaali-peeli taxi drivers in bombay.

and to somnath – why would you take a taxi (in the first place) from bandra station to kalina (in the second place).

LikeLike

Can you imagine reaching for an important meeting/appointment in relatively “clean” state in pouring mumbai rain in an autorickshaw?

LikeLike

Attacking passengers in Kochi : Four auto drivers surrender

http://www.mathrubhumi.com/english/story.php?id=125128

This is what happened in God’s own country!!!!!!

LikeLike

Panel may fix auto, taxi fares by July 12

http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-05-19/mumbai/31777173_1_auto-drivers-autos-and-taxis-auto-union-leader

The Auto and Taxi fares are fixed by the RTO in consultation with the Drivers & Owners Unions and Consumer Groups. If the Drivers think that the fares fixed are not fair, they should take up the matter with thier Unions who in turn will take up the matter with the relevant authorities. Once the fares are fixed, the Drivers should strictly adhere to the same. Fleecing the passengers shoud not be allowed under any circumstance.

LikeLike

Well, the article does not consider that the campaigns for reforms in Auto-rickshaw sector in Delhi are led by Nyayabhoomi and Prabodh – both NGOs run by not-elite and not-poor and hence middle class groups of individuals. Check out the link to the documentary by Prabodh – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVWjuH8p1_Q

Also, one could ask counter-questions: the onus of being inclusionist lies only on the middle class…? I have asked the drivers number of times – why don’t they go on a strike for more permits rather than fare hike? They agree and so all most all stakeholders that more permits is the solution.

Politics on the lines of class ceratinly cannot provide any solution to this problem. There are vested interests at the top level that are not letting the supply of permits increase despite the consensus among rest of stakeholders except policy makers and auto financiers. Follow the litigation at the Supreme Court and you will understand the real politics behind it.

LikeLike

Thank you for this article. One of my classmates at my University in California used this appalling cartoon in a lecture about about Race and Class as an example of what the phenomena of the elite organizing for ‘justice’ looks like. I’m from Bangalore. I’m glad there was dissent to this kind of complete and absolute lack of awareness about the idea of privilege, and what it means to locate oneself as an artist in it. Thank you again Gautam!

LikeLike