Guest post by ZAHIR JANMOHAMED

When I started conducting research in Gujarat two years ago, I kept being asked the same question among middle class youth in Ahmedabad: “Have you read Chetan Bhagat?” When I asked what other books they have read, I often heard, “Actually I only read Chetan Bhagat.”

So I started to read Bhagat because I wanted to relate to many of the young people I was interviewing. But it was not an easy task.

I understand the frustration with Bhagat’s writing. Unlike other young adult authors like JK Rowling or Suzanne Collins, Bhagat’s books rarely reward a second reading (and yes I have tried).

Partly this is because Bhagat does not write ambiguous characters—the MBA student, for example, will act greedy and will learn that he needs to loosen up; the mischievous boy will understand there are costs to his deviousness. Reading a Bhagat book is like scrolling through a Facebook timeline—we are just checking in on what people are doing, catching momentary glimpses of who they are, but we rarely learn about the interior journey of each character.

Bhagat is not, however, without talent and his strength is his pacing. He knows how to remove the hiccups that often slow a story down and many Gujaratis I meet tell me they do not read but make an exception for Bhagat. But Bhagat’s pacing is also his weakness. Jonathan Franzen often says young authors today write novels like television. Modern television owes much of its influence to the music video with its non-stop cutting. If we are bored with an image, chances are a new image will appear 10 seconds later. The same can be said with Bhagat’s books—if a scene tires us, a new one will appear a page or two later.

This might be an unfair critique of Bhagat as story is not Bhagat’s goal — this much he has admitted. He is interested in imparting messages and perhaps this is why his books suffer from such a stubborn unwillingness to be imaginative. His books read like op-ed pieces, each character a different Lego block in his argument. In 2 States, for example, the message smacks us on every page: it is not a big deal to marry a person from another state. Great but can we at least be treated to a more complex story along the way please?

Of all of Bhagat’s books, I was most intrigued to read The 3 Mistake of My Life because it is set in Ahmedabad during the 2001 Kutch earthquake and the 2002 Gujarat riots. In this book, Bhagat gives us characters with about as much depth as a cardboard cutout: business minded Govind who is uptight; a religious boy named Omi who is sensitive and impressionable; and an unruly jock named Ishaan who loves cricket.

In the book, Ishaan befriends a young Muslim boy named Ali with a remarkable talent for cricket. For a novel set in Ahmedabad—where Muslims are routinely vilified—I salute Bhagat for writing a book with a sympathetic, central Muslim character. And I commend Bhagat for weaving in the stories of the 2001 earthquake and the 2002 Gujarat riots even though he fails at rendering both events with much complexity.

However in trying to tear down stereotypes, Bhagat fortifies many others. When Australia comes knocking on Ali’s door, Ali refuses saying he loves India much more. We cheer for Ali not because of who he is (Bhagat has given us little clue on who Ali is as a person) but because Ali loves India so much. Hmm—is this the only reason to cheer for an Indian Muslim? Because the Indian Muslim loves India so much?

Ishaan is made to seem like a savior. Without Ishaan, Ali would just be a kid in a kurta pyjama wearing a topee. Does a Gujarati Muslim not have agency of his own? In Bhagat’s world, it appears not. They reach their goals through the help of very kind Hindus.

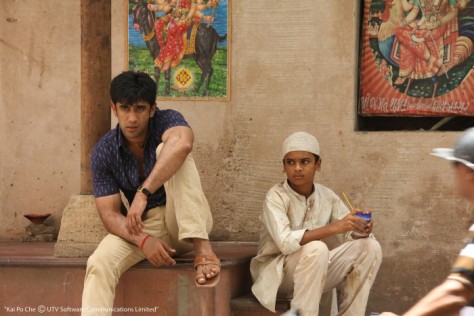

Thankfully the movie version of The 3 Mistakes of My Life does not suffer from these same faults. Bhagat co-wrote Kai Po Che and the movie follows the outline of his book. The movie gets many things right. The three main characters are rendered with greater depth, humor and compassion. Director Abhishek Kapoor has given them texture and contradictions, something often lacking in Bhagat’s books.

There are other redeeming things about the film. Kai Po Che lacks many of the stereotypes we often see in Hindi films about Gujarat and Gujaratis. The characters do not sit around and talk about how much they like dhokla and they do not dance to awful songs like “GUJJU”. The Gujarat landscape is also as much a character in the film and I appreciate how the director showed the varied, natural beauty of this state.

The lead female character, played by Armita Puri, is smart, funny and assertive. She is not made to do any item numbers and her relationship with her teacher shows the changing ways males and females interact in middle class Gujarat.

But where the movie fumbles is in showing the Gujarat riots of 2002. When the earthquake happens, we see the ground shaking, the roof crumbling down, and Omi running for cover. We see the personal loss of the earthquake on the three boys. The earthquake affects them directly and we watch them in tears counseling each other. It is hard not to be touched and the cut to intermission only intensifies this. After the intermission, we see shots of bodies being carried, a relief camp set up for the 2001 earthquake, and even the death toll flashing on a TV.

But the director—and Bhagat’s script—fails to show the same detail for the 2002 riots. The scene begins when we see Omi dropping off his parents at the train station in Ahmedabad. Moments later Omi learns his parents were in the fateful S6 coach that was tragically burnt on February 27, 2002 in Godhra.

Omi is shattered and as an audience we are too. He meets his uncle, a leader in a Hindu group, and they console each other over the train burning. As an audience it is easy to sympathize, maybe even support, their desire to seek revenge. We even see a shot of a TV report that shows the exact number of those killed in Godhra.

That evening, Omi and his uncle carry swords and guns and storm a Muslim locality. Using an old fashion style ram, they knock down the door to a Muslim locality—conveniently decorated with green and red crescent stars—and start killing Muslims. Caught up in the middle are Ali, Ishaan’s star cricket student, and Ali’s father.

There are several problems with this scene and the way the film portrays Muslims.

Every time we see a Muslim character, the males are wearing kurta pyjamas and topees and the females are wearing burkhas. The film only exacerbates a prevalent attitude that Muslims look and dress different. This may be true some of the time but it is not true all the time, as Kai Po Che would have us believe.

As the riots unfold we do not see the meticulous lists passed out on the evening of February 27, 2002 of all the Muslim businesses and homes the mobs attacked. The riots we see onscreen are shown as a reaction to the Godhra attack and not, as many have pointed out, a pre-planned attacked orchestrated by the Gujarat state.

What struck me about witnessing the 2002 riots were the number of places in upper class areas of Ahmedabad like CG road where businesses with ostensibly non-Muslim sounding names—Pantaloons and Metro Shoe Store—were burned by mobs driving the latest SUVs. The movie does not show this. The movie does not also show on a TV screen the number of those killed in the riots, as it did with the death toll for the Bhuj earthquake and the Godhra train attack.

In one scene in the movie, the riot is staged to make it seem like a fight between an equal number of Hindus and Muslims. This is not what happened. It was thousands of people gathering to attack often just one or two businesses on otherwise Hindu streets. It was, in short, not a riot as the film would have us believe. It was a state sponsored pogrom.

It is what we do not see in the film that is most troubling: we do not see police officers refusing to help; we do not see women being held down by mobs, raped, and then burned alive; we do not see entire families being thrown into bakery ovens; we do not see the Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi meeting with police officers and instructing them not to intervene. In fact Modi is nowhere to be seen—not surprising, given Bhagat’s affinity for Tweeting pictures of him and Modi.

Yes—we watch Ali and his father being chased by the mob. But then the tension shifts when Ishaan reads one of Govind’s text messages and the sympathy quickly shifts away from the Muslims being attacked to the three boys. I will not ruin the final scene but we are left feeling a profound loss—again not for Ali or his family or for the Muslims attacked during the riots—but for one of the three boys.

There are no shots of the relief camps built for the survivors of 2002 riots (there were 85,000 displaced in Ahmedabad alone), nor are there shots of entire rows of homes burned down. The three characters are not seen crying in the aftermath of 2002 nor do we see what has happened to Ali, his family, or his neighborhood as a result of the riots.

The movie then cuts to the final scene where the film ends on an upbeat note. This is, after all, a Chetan Bhagat movie. He wants you to leave the theater as you entered: feeling comfortable.

I recognize the challenge of converting a book into a movie and I agree it is unfair to say the film did not show everything that happened in the riots. The film is not about the riots. It is about the three boys and Kai Po Che is an excellent film about how friendships change (and are tested) through time. The director does weave in many admirable things, including a relationship between Ishaan and Ali that is very endearing.

But it could have been so much more. Just as the film showed very poignantly the lives destroyed by the 2001 earthquake, a few more scenes—maybe even just one more minute of screen time—could have given a short glimpse into how 2002 destroyed so many lives. Bhagat said he wanted the film to be a tribute to Gujarat. And it is. But it also contains something more insidious: yet another reduction of the Gujarat riots of 2002.

(Zahir Janmohamed lives and writes in Ahmedabad. Email: zahirj at gmail dot com.)

Related post from Kafila archives:

Previously in Kafila by Zahir Janmohamed:

- Sanjay and me

- Prof VK Tripathi and the fight for schools in Juhapura

- Seeing Pakistan from Juhapura

- An open letter to Madhu Purnima Kishwar

http://kafila.org/2013/02/24/sanjay-and-me-zahir-janmohamed/

awesome… actually in hindi films they are not free from what is called ‘dhirodatt nayak’. they often failed to show the plot of film where it is placed. and obviously when its come to some sensitive matter they ignore in order to make someone happy or not to make someone annoyed

LikeLike

I have not read Chetan Bhagat’s Three Mistakes of My Life but based on multiple (and it must be said, futile) attempts to get through Five Point Someone, I have no doubts that Kai Po Che is a vastly improved rendition of the book version of the story. I found the film about three friends in Ahmedabad in the 2000s to be compelling, the characters richly and believably fleshed out. When the character of Ali Hashmi – the young cricket prodigy picked out by Ishan – first came on screen, I also prickled and remarked that he was shown in kurta-pyjama and skull cap. As though the name Ali Hashmi were not in itself enough to underscore his otherness in the context of Gujarat, I thought to myself.

However, as the film unfolded, I felt that this visual marking of Ali was not necessarily borne out of the usual Bollywood impulse to signal `Muslim’ through predictable shorthand. On the contrary, I was pleasantly surprised that the Muslim characters in the film were not shown attending madrassas, reading the Koran, attending Qawwali sessions or dargahs, nor indeed were they dealing with underworld crime dons. I think the film has to be lauded for steering clear of some of the most typical personifications of Muslims in popular Hindi cinema. For me, the depiction of the forlorn character of Ali, with his skullcap and kurta, shooting his marbles alone in a corner, was actually a visual strategy that helped develop his otherness (as Muslim, as a loner, as a resident of Juhapura) in a poignant way, in a way in fact that led to a strong emotional connect with the audience. This boy is clearly one that the audience is meant to empathize with. Moreover, it is not just the Muslims who are exclusively selected for visual marking. Hindus in the film (particularly communal ones such as Omi’s uncle, the head honcho of the local Hindu nationalist party or his sidekick, Vishwas), are shown with particularly prominent, saffron tikkas.

Where I would disagree more strongly with Zahir Janmohamed however, is in my reading of the relative weightage given to the earthquake and the pogrom in the film’s narrative structure. Unlike him, I do not agree that the earthquake was dealt with in detail and the riots were not. I think the subject matter of the film was neither the earthquake nor the riots per se. In fact, I see the relative import of the riots not in the scene where Govind is woken up with the walls shaking, plaster falling from the ceiling onto his face, nor in the scene where the three friends console each other over the loss of the shop they have just invested five lakhs in. The real reason why the earthquake is important for the film – as indeed in real-time Gujarat – is for the scene in the relief camp, where Ali’s family is denied food tags by Vishwas. This is the turning point in the narrative of the film when the discourse begins to shift most explicitly to ‘us’ and ‘them’ – hamare log and the others. While there are stray references to this before (as when Omi’s uncle berates the boys for dealing with Hassan bhai, a property agent, when they could have been dealing with a Hindu) but it is only after the earthquake that the discourse around Muslims shifts in a much more pronounced manner, becomes far more explicit. As an ‘event’, the earthquake was not detailed with any nuance at all. Death toll figures flashing on a tv screen cannot be mistaken for narrative nuance.

Which brings me to my final point – the ‘reduction’ of 2002 in the film. All the claims made by Zahir Janmohamed are true. The film makes no reference to the systematic, targeted pogrom that was unleashed by the state against Muslims in Gujarat in 2002. It does not show the brutal rapes of women, the foetuses torn out of wombs, the chilling and cold-blooded murder of men, women and children while the law enforcement agencies stood by and watched. However, we must ask ourselves if the depiction of all of the above on film, are the only ways in which we can memorialize the events of 2002 and after? There is a snatch of dialogue where one of the characters talks of how he has been dialing the police but there has been no response. Very poignantly, Ali’s father – when the marauding Hindu mob chanting Jai Shri Ram, is at the door of his pol, demanding that the Muslims come out of hiding – asks his adversaries to stay calm and appeals in Gujarati – aapne vat kariye chiye – let’s talk this through. One could argue that crucial lines like these ought to have been subtitled for a non-Gujarati speaking audience for their full import to sink through, but I would say this is indictment enough of at least some of what we now know as the reality of 2002: the vulnerability of the Muslim in the face of the organized mob on its doorstep.

Much, much more problematic for me, is the reduction not of 2002 (indeed I applaud the fact that a mainstream Hindi film has shown whatever small slice of what happened with a remarkable degree of honesty) but of the complete cop-out at the end. The film ends with a feel-good scene where perpetrators and victims are seamlessly reconciled while Ali Hashmi has shed the ghosts of the past to become India’s new cricketing sensation. All is right with the world, and Gujarat is as vibrant as every tourism poster proclaims it to be. It is here, in the last five minutes of the film, that it is at its most problematic. Indeed, it is almost as though the preceding two and a half hours are wiped out. Forgive and forget. We have moved on. Reconciliation obviates the need for justice. This is the real reduction – and effacement – of the way things really are in Gujarat.

LikeLike

I agree with this very well written comment. Although, I would point out that Omi is shown to have spent ten years in jail. But the idea of cricket and flag waving nationalism being enough to overcome the past was indeed very disappointing.

On a side note, I found the idea of Ishaan getting enraged about his sister’s willing relationship with Govind quite regressive, in an otherwise welcome departure from the usual ultra ‘masculine’, patriarchal Indian hero that movies like Dabangg, Rowdy Rathore and Singham embody.

LikeLike

I found Ishaan’s reaction in keeping with his character, he earlier breaks a car whose driver was stalking his sister. He is not a thinker, he is a regular guy, and ye, its the girls today who are more progressive, than the boys, in lower middle class society.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. Both the article and this critique are fair and illuminating. I found Snigdha’s shrill denunciation of Chetan Bhagat, a bit of an own goal for the left. Modi is ascendant today, elections are coming, and suddenly this movie brings the riots into the popular consciousness. It also robustly criticises political fundamentalism, and yes the comment about the earthquake as the turning point is absolutely spot on. I think nuanced commentary like this does much more for the left, secular viewpoint than shrill criticisms that the movie does not villify Narendra Modi or does not present an authentic depiction of the riots. At the end of the day, Bollywood is about bouncy optimism, given that limitation, the movie does a great job. Would you rather the movie was no made? And yes, very respectfully I would like to get a sense of what Muslim intellectuals feel about the Godhra incident itself.

LikeLike

Farhana … good wiriting. Thanks.

LikeLike

You are a wonderful critic…! But I agree with you!!

LikeLike

it’s a commercial film, not a documentary, you nincompoops.

LikeLike

Good points all. But given it’s based on a Chetan Bhagat book and is co-written by Chetan Bhagat, I think what the audience got was a lot more than what it expected. There were several such abrupt moments in the film that took away from delving deeper into several subjects and characters, but that said, the film is not short and length would have become a casualty. Finally, I have to say this – I was expecting a scene showing Omi’s parents being charred in the fateful train. Interestingly, that didn’t happen. That would have pushed the “justification for the riots” bit even more. I don’t know if that an intentional move to not ignite any more sentiments than are already aroused.

LikeLike

whenever gujarat name is taken always riots of 2002 will be brought into picture but why not godhra massacre brutality? who r u tell the riots are not the after effects of godhra train burning incident?

LikeLike

‘Kai Po Che’ proves that the IIT/IIM-bred intellectualism of our Bhagats/Kapoors doesn’t allow an engagement with the Gujarat riots. And, they should just refrain from pretentious critical posturings about it.

To say that the 2002 communal violence could’ve been a result of personal trauma/loss suffered by Hindu families [read:sons, brothers, brothers-in-law] bereaved by the Godhra incident is not only a gross political error, but also an attempt to legitimize the riots as ’emotional retaliation’. Second, to place a vacillating otherwise-innocuous teeka-dhaari good-boy-Hindu orphaned by Godhra as the protagonist of the rioting forces is to further sanitise and normalise the fundamentalist ideology of Hindu terror. Third, to portray the rioting faction as an electorally-defeated party (or, as belonging to the political opposition) and thus separate it from the role played by the state machinery is to underplay the horror of 2002 as ‘simple’ mob-action. Finally, to begin by representing the shopping mall space as wombing the dreams and aspirations of the unemployed struggling youth is to shamelessly vindicate the myth of ‘development’ that Modi’s trying to wipe the memory of 2002 with.

This said (and much much more…), a Bhagat can only remain a Bhagat. And, raving viewers/reviewers too will remain.

LikeLike

It is not democratic to ask people to refrain from commenting. All historical incidents will be processed in their own way by the public. That said your critique was the most trenchant of all that I have read so far.

LikeLike

Did the movie say that it was a documentry about the genocide of 02′?Why look for political meanings in situations when none exists?The movie is a tale of three friends making their careers at a time of great upheavel in the state of Gujarat… there is no attempt to win any sympathy for any side and the only person who comes out villanous is the uncle who seems to be settling political scores right throughout…

LikeLike

Great review Zahir. It is unfortunate that India does not have recourse to documentary films and we expect tinsel-town to be the bearer of the truth. Bollywood, then, will most often miss the point as it succumbs to the movie-magic of “happy endings”.

Apart from the 2002 Gujarat riots being an unequal revenge for the Godhra train burning, there is also a vague but convenient suspicion that Muslims in India harbor terrorists ideals. This is obviously baseless and actually far from true. There are no takers for the terror creed, because India has provided a platform for an individual’s aspirations to be successful, where every Muslim feels connected to the same higher goals of livelihood and success that any other person from any other faith in India does. To say that this aspirational lifestyle of a society was the handiwork or invention of Modi is like thanking the weatherman for the beautiful weather.

A 2005 wikileaks cable sent by David Mulford to the US State Department sheds some light on why Indian Muslims eschew violence:

LikeLike

you answered your question when you said –“But then the tension shifts when Ishaan reads one of Govind’s text messages and the sympathy quickly shifts away from the Muslims being attacked to the three boys. ” ..This movie is not about how gruesome riots were in 2002..It is NOT an indictment of any party or group..It is movie about 3 friends and earthquakes and riots are side stories leave alone side characters in the movie..You must give credit to the filmmakers that atleast they havent shied way from showing that muslims were targeted by Hindu groups. We have news channel who use euphemism like majority and minority communities..If you really want to make comparisons then compare it with friendship movies like Rock On and Dil Chahta hai..

LikeLike

Hi Zahir, I have been following you on twitter and have been reading your articles a lot recently and even if I may not totally agree with them I never see any dishonesty or manipulation. You have seen Gujarat riots closely and have been close to sufferings of Gujarati Muslims. Therefore when a mainstream film depicting Gujarat riots comes, I understand that you may expect it to deal with it in all its complexity and detail. But I think in a scenario where no mainstream filmmaker even dares to deal with sensitive socio-political events of the country, I believe due credit must be given while also recognising the practical considerations that the filmmaker have had to go through. FIrstly as you said that the focus of the film was not the riots/earthquake but the friends therefore I find it unfair to criticise the film for not dealing with everything around the riots. Even then the film has challenged the Hindutva discourse that solely blames the Godhra incident for riots. The Hindutva political involvement was clearly build-up throughout the movie where Hindutva party’s anti-Muslim stance was clearly shown. Ishaan had a fight with Omi and blames him for him also speaking his Mama’s anti-Muslim language who was clearly shown to be an influential Hindutva politician. When the riots begin, it was clearly shown how Godhra incident was ‘used’ by Hindutva leaders to incite riots. The film’s characters were not shown to be ideal. Even if Omi was involved in the riots angered by his parents death, it was in no way justified as right. Even if the movie’s focus was to be Gujarat riots, do you really think it was possible for the filmmakers to show things that could have resulted in legal as well as practical issues that could have resulted in the film not getting a release at all. All the media discourse with regard to Gujarat riots already focus on Modi, but the film manages to depict Hindutva politics and common people’s involvement in the riots. Also if it doesnt directly speak about State involvement, it neither pretends that riots were purely a reactionary act by angered Hindus and neither shows any police/state action preventing the riots. Lets have some regard for the tightrope that the filmmakers would have had to walk while dealing with Gujarat riots where they couldnt go all the way but also managed to show them without manipulation. Also importantly this is an Abhishek Kapoor film where Chetan Bhagat was involved. I say this because Bhagat’s political tendencies can result in certain pre-meditated suspicion. I am not trying to say that the film is above criticism in terms of depiction of sensitive events but when a filmmaker deals with it, instead of being overtly suspicious we need to understand various considerations they have to go. The film has made those who justified Gujarat riots most uncomfortable who have been manipulating the reasons for it and for a mainstream film to deal with it is no mean thing.

LikeLike

Can understand critic’s criticism of the film, however, I disagree that the film has reduced Gujarat riots of 2002.

The very fact that Omi leaves his anger, his mindlessness to have joined the rioters, and regrets having done what he did upon the loss of his dearest friend and repents, yet is unable to make up for the loss, the void in his and others’ lives that his act created (as shown by his cries during the last scene) gives the intended message.

LikeLike

I was greatly disappointed with this critique of Kai Po Che. Being witness to the Gujarat riots Zahirji has let his personal experiences cloud his objectivity in analysing a commercial movie whose central theme is friendship. It is not a docudrama on Gujarat riots nor does it claim to be. Most disturbing is that he sees even innocous events in the movie with suspicion. Take for example Ishan helping the muslim kid Ali. He sees this as stereotyping hindu muslim relationship as one between unequals. Have no Hindu helped a Muslim in this country? Does one have to stretch his imagination inorder to comprehend a Hindu helping a muslim boy? It is a fact that standard of living of Hindus is much better than Muslims in this country for whatever reasons. So what if it is played out in the movie. As far as the depiction or non depiction of the brutality and motivation of the Gujarat riots are concerned it should be borne in mind again that central theme here is the relationship between the three friends and how it is affected by the events in their immediate surroundings. Whether the riots were spontaneous or directed from the CM’s office will not change the course of the story. Finally Zahirji is just about tempted to try his hand at the favourite passtime of India’s “intellectual”- Chetan Bhagat bashing. But thats for another day. I am sure Zahirji will chronicle everything he has found lacking in this movie in the book he is writing. Am eagerly waiting for it. Best wishes.

LikeLike

Wait, you feel indignant about Bollywood’s portrayal of your people and the depiction of certain events? Kindly join the back of the queue, along with South Indians, Sikhs, Marathas, and- you get the idea.

More seriously though, I would think that it’s optimistic at best and ridiculous at worst to watch a mainstream Bollywood flick AND expect a documentary-style treatment of ONE of the passing events in the story.

For what it’s worth, there are other movies that deal with this subject, movies that intended to be informative- and a critique of them would probably be more meaningful.

Also, I think the book and movie both deserve some credit for unambiguously rejecting any justification for the events of 2002.

LikeLike

I think rather than critiquing the film for missing out on details, I think Kai po che is a reason to celebrate! First time ever, a mainstream film has dared to even acknowledge that the program happened. If it had got a bit too ‘daring’ then either it would have been rotting in the box for decades or would have been dismissed by the majority of cinegoers as too arty for their taste. I think its a film about humanism. And the maker has done full justice to that objective.

LikeLike

Ridiculous article to say the least – nit-picking over what is NOT in the movie. Neither the writer nor the director have claimed that they are making an definitive version of the 2002 riots. It is a story set in 2002, and they have a right to say it the way they want (And yes, Kafila has a right to talk about what is not in the movie and I have a right to say it that such talk is ridiculous).

By the way, I searched for an article to check Kafila’s viewpoints on the “hurt sentiments” during Vishwaroopam row. Did not find one. Actually, had not cared about it, but searched for it anyway so that I can say “the sickening forgetfulness of Kafila”.

LikeLike

Mr. Janmohammed, you review an out-and-out commercial movie, produced under the UTV banner, (and based on a Chetan Bhagat book no less) with expectations of honesty and sensitive portrayal of a controversial issues? You pick apart a movie nobody claimed was a jolt of reality, for stereotypes, shifting empathies and reductions. You knew how weak the book was. You knew the movie was based on the book. May I ask if this is the first ‘Bollywood’ movie you have seen?

I would rate the movie highly for avoiding any controversy at all and doing well what is set out to do in the first place…be a box-office hit.

LikeLike

Hi,

Thanks for an exhaustive review of the movie. All I could think of, while reading, this piece was ‘political conservativism’ where people keep forgetting deeds of leaders and everything is merely reduced to power Relations and a nexus of political leaders and economic growth. Now ‘model modi’ is projected as our only way to prosperity and a chance to redeem window of opportunity.

LikeLike

Well I think what is missing from all the responses and the article itself is that the police do not pick up the phones. Secondly, the scenery that is really captivating is Diu, the Fort etc. Finally I think there is one important element of metaphor which for me is important—- the killing of Ishaan. For me this is a metaphor for the killing of all that is secular and the film is a strong comment on that. Ishaan’s ghost for me is this hope that secularism is not dead and is hovering somewhere in the background. Unfortunately only as a ghost of what once was a secular state. The Raheja Complex collapse etc. are a comment on the business model of Gujarat and the absolute corruption of the system Modi or no Modi. I wish some one would comment and critique what i have to say.

LikeLike

From the author of the post, Zahir Janmohamed:

Thank you all for your comments and criticisms.

I normally do not respond to comments but I felt I needed to do so because in hindsight I got many things wrong about “Kai Po Che” and I wanted to clarify/to correct some of my views.

The first mistake I made was in assigning too much blame to Chetan Bhagat. I understand that he wrote the script with several others and to single Bhagat out is unfair. Film is by nature a collaborative process—the director, the producer, the director of photography, and so many others all have inputs and the final product is the result of many, not just of one.

Second, upon viewing the movie a second time, I am inclined to agree with this comment by Farhana: “I do not agree that the earthquake was dealt with in detail and the riots were not. I think the subject matter of the film was neither the earthquake nor the riots per se. In fact, I see the relative import of the riots not in the scene where Govind is woken up with the walls shaking, plaster falling from the ceiling onto his face, nor in the scene where the three friends console each other over the loss of the shop they have just invested five lakhs in. The real reason why the earthquake is important for the film – as indeed in real-time Gujarat – is for the scene in the relief camp, where Ali’s family is denied food tags by Vishwas. This is the turning point in the narrative of the film when the discourse begins to shift most explicitly to ‘us’ and ‘them’ – hamare log and the others.”

Farhana makes an important point which is something I never thought of—the film does show the fracturing of Gujarati society and the biggest problem, as Farhana writes, is the end. She writes, “The film ends with a feel-good scene where perpetrators and victims are seamlessly reconciled while Ali Hashmi has shed the ghosts of the past to become India’s new cricketing sensation.”

I am grateful for her comments and I am inclined to agree with her almost completely.

I could have viewed those final scenes in a different way and after I read all the comments on this post, I reconsidered that last scene once again.

I think a compelling argument could be made—as my close friend Arastu has done so—that the riots were indeed shown with authenticity and sensitivity.

Third and perhaps most glaringly, I viewed the film in a vacuum, not understanding the context of how Indian viewers would react to the movie.

I commend the film for showing Godhra and its ghastly tragedy. This is important as those lives killed in Godhra should and must be honored.

I should note that the film did not show the Godhra attack on screen—it is off screen and yet it retains so much power. Likewise maybe the film’s power was not what it showed but what it did not show. I faulted the film for not showing more about the Gujarat riots—maybe that was its strength. It moved us not only by what it showed but what it did not show.

An argument could be made that Bitoo Mamu was the villain of the movie. That indeed is a bold movie as there are so few critiques in India cinema of Hindutva leaders.

Likewise an argument could be made—as my friend Arastu has done so—that Muslims were shown with great sympathy, that for a Muslim kid in a topee to rise up to become the hero shows a trajectory that we do not often associate with someone who dresses like that.

And another comment by Aseem, via Twitter, writes that if the film showed much more, it would not have been allowed to be screened in India. Likewise another comment by Rana writes that for Indian cinema, “Kai Po Che” is a huge step forward. Aseem knows far more about Indian cinema than I do and I defer to him on this.

The question then is–why not ask Kafila to remove the piece? I thought about that but I hope that my piece, as flawed as it is, raises some questions and sparks debate, even if much of the debate is in critiquing my piece.

So why then post this comment at all?

One of the things I love about writing is that writing helps me learn about myself and the world. When I watched “Kai Po Che” I had strong misgivings about the film and I still hold much of these misgivings today.

But I failed to articulate my points as well as I could have and I should have. Many people pointed out some very sound problems of my piece. In the future I will try to be more nuanced and considerate when articulating my viewpoints and I thank you all for your comments.

LikeLike

Zahir, I greatly admire you for this comment as I often see writer/opinion makers refusing to accept that a piece of their may have some issues for fear of losing credibility. I think the burden of always being perfect is one of the big obstacles any writer can face so I dont think there is any reason to remove/discredit this piece but treat it as opening a discussion which you have succeeded in while also acknowledging that what you initially felt about the film had some problems.

A couple of points I wanted to make other than the one in my previous comment. There was a scene in the film after Godhra incident when a truck full of boxes of swords came. It was a strong indicator that the riots weren’t just spontaneous(though Godhra incident helped to trigger it) but that weapons were all prepared.

Secondly while I completely agree with what Farhana pointed out regarding the film, I didnt find the ending to be about forgiving and forgetting the Gujarat riots or reconciliation between the victims and the perpetrators of the riots. It was reconciliation between the protagonists of the film and their personal tragedies. Omi was shown to have faced a sentence(he was part of the anti-Muslim riots and was responsible for death of Ishaan) and realised his guilt and was sorry for it, his Mama died in self-defence by Ali’s father. Ali as an individual was not shown to lose anyone in his family. The ending didnt talk about perpetrators and victims in totality because that wasn’t the subject matter of the film while the riots segment didnt compromise on showing who the perpetrators and victims were.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment.

I’ve commented before but wanted to add another comment on this particular line :

“Ishaan is made to seem like a savior. Without Ishaan, Ali would just be a kid in a kurta pyjama wearing a topee. Does a Gujarati Muslim not have agency of his own? In Bhagat’s world, it appears not. They reach their goals through the help of very kind Hindus.”

Ali’s trajectory from prodigy to become a player on the national team takes place AFTER Ishaan’s death. The movie itself does not attribute Ali’s eventual success to Ishaan, so I think it is a bit unfair to claim that Ali is depicted without agency.

I am a bit on the fence about the final scene.I saw it as a resolution amongst the protagonists of the story and the posthumous realisation of Ishaan’s dream to see Ali play for India. There was no larger commentary on Gujarati society or the after- effects of 2002 (which was in keeping with the theme of the entire story) – and any interpretation of the climax in such a manner will rather futile as it will involve a considerable amount of extrapolating.

LikeLike

A few stereotypes and there is something wrong with the film? I am sorry but that is an absurd line of criticism.

As for the depiction of the riots, there is no responsibility on part of a film-maker or writer to stick to a detailed narrative about the Gujarat riots. As you said “the film is not about the riots”. The politics depicted in the film must be judged accordingly.

LikeLike

I really appreciate your clarifications though.

LikeLike

I recently spoke to a Bombay filmmaker about Zahir Janmohamad’s take on Kai Po Che. He said, “Anyone who knows the Indian filmmaking scenario cannot argue like this”. It is true that films which represent real-life events run into all kinds of trouble in India — from the government, the censors, the multiplexes. But how can we run away from that niggling thing called the truth? Must we not represent reality more responsibly? There are filmmakers who have fought censorship and the Indian government to have their voices heard. I can think immediately of Anand Patwardhan.

Janmohamad’s review is courageous and he isn’t misplaced in asking for a minute of extra screen time to hint at the pogrom. Such critique is essential for Bollywood cannot be divorced from ‘the real world’. True, political accuracy may have ruined the film’s chances of being shown in Gujarat. Speaking objectively, however, the film tries to reinforce the idea that religion needn’t be a barrier or even a consideration when it comes to something you love. But will it inspire Hindu kids to play cricket in their Muslim friends’ neighbourhood grounds in Juhapura? I really don’t know. If it did, I might be willing to concede that that extra minute can be left out.

LikeLike

Thank you. That’s a wonderful review, that I read as I go to watch the movie.

As you pointed out, it’s appalling that the movie is yet another attempt to re-write history.

LikeLike