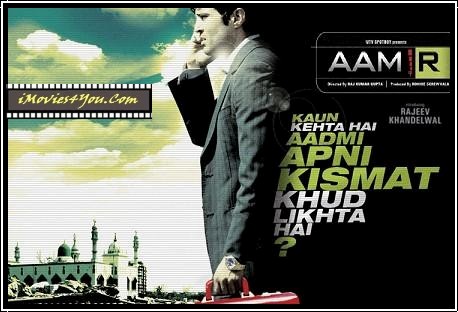

Aamir, a film about a man on the run, was released in June 2008, it was one of those rare films that was praised by critics and liked by viewers. I did not like the film, I was in fact very upset and disturbed about the film and thought about giving expression to my angst in writing, but this outpouring of powerful emotions never materialised, I would probably have never gotten down to writing this piece had Delhi 6 not arrived on the scene.

I liked Delhi 6, but I was once again on the wrong side, well almost, aside from a handful of insignificant others like me, everyone including the critics was panning the film. This set me thinking about this major disconnect between everyone else ranged against ‘the insignificant others including I’. Is it possible that I did not understand cinema or is it that both the popular and elitist perceptions have gone through a tectonic shift without me and the aforementioned handful realising this. I think the frame of reference has changed and we are still stuck within a world that no one seems to remember, relate to or care about.

It is this feeling of extreme disquiet that has compelled me to revisit Aamir and to put forward my case about not liking the former and liking the latter.

To begin with Aamir. As already stated, this is the story of a man on the run. Aamir, a young doctor practicing abroad, returns to Bombay, to spend time with his mother and siblings, the immigration officer asks him meaningless questions, casts aspersions on him, checks his papers again and again, eventually letting him go, albeit, reluctantly. Aamir picks up his stuff and asks the immigration officer, “would you have treated me thus, had my name been Amar” and walks off.

He steps out, his luggage is snatched, two bike riders zoom in, shove a phone in his hand, the phone is ringing, they shout “talk” and ride off. The voice on the phone tells him to follow instructions if he wants his luggage back. Aamir is now made to do a whole range of things, go to a filthy chawl, ‘ a muslim chawl’ walk into the putrid and stinking toilet, is told that is how ‘we are made to live’, he is told that he has forgotten his roots, forgotten his faith, betrayed his people, etc.etc.

Aamir, blows hot and cold, says he worked hard, went abroad on a scholarship, made choices. He is told that his people have no choices, they are condemned to live in these chawls in this filth, in poverty. Aamir insists that he wants none of this he wants his luggage back and wants to meet his family.

He is directed to a restaurant, ‘a muslim restaurant’ people are gorging themselves on huge chunks of meat, everyone consumes phenomenal quantities, they eat like animals, he receives a phone call, is directed to another place then to another and yet one more place, while criss-crossing the Muslim ghettoes of Bombay, he goes through a meat market,-huge chunks of meat hang on both sides of the street. Aamir walks to his next rendezvous – a seedy hotel, he is propositioned on the staircase by a prostitute, once inside the room he is served a huge quantity of food, large chunks of meat, told to eat, rest and wait for instructions. Another phone call, he is told to deliver a suitcase of money at an address to be supplied to him, he is also told that he is free man after he has run this chore, his luggage will be returned and he can go to his family.

He refuses, is made to listen to the cries of his mother and siblings and told, do as your asked or you will never see them again. Aamir agrees, sets off, is attacked, brief case is snatched, he wanders bewildered. The prostitute meets him again, guides him to where his attackers are hiding, he barges in beats up everybody takes his bag. The phone rings again, he is asked to get into a specific bus, sometime later he is told to slip the bag under the seat and get off. He is told you only have two minutes, he gets off.

The viewers and Aamir, realise that the snatching was a charade, the suitcase is now a bomb, the attackers, the prostitute, the bearers, the man on the phone, everybody is part of the network of terror. Something breaks inside Aamir, he rushes in drags the brief case, rushes out shouting bomb bomb, people digging a trench jump out and run, Aamir runs to the trench, the brief case explodes. End of Aamir, end of Film. Teary eyed and clapping the viewers depart.

On the face of it a film about innocents being dragged into the game of terrorists, helpless innocent people – struggling to rise above their meagre circumstances – being dragged down by the fanatics to serve their nefarious designs. The heroism of the ordinary individual sacrificing his all to single handedly foil the well laid plans of the enemies of the nation.

But this is only a disguise for very cleverly reinforcing every stereotype about the Muslim. What is going on around Aamir is the actual message of the film. Every step that Aamir takes is reported back to the boss man at the other end of the line. The entire city, or at least the parts where the film takes you, and it takes you to all the Muslim ghettoes – for Muslims live only in ghettoes- has people in beards, dressed like the stereotypical Muslim of the DAVP hoardings, constantly talking in an agitated tone on the phone. They are the network of terror, reporting constantly to the boss. Every restaurant owner, every bearer, every paanwallah, every chaiwallah, that the hero talks to, is part of the network.

Needless to say they are all Muslims, look at their faces, they are cruel faces, faces of killers, faces of scheming little crooks. Great care has been taken to select these secondary and tertiary characters. Except for Aamir and his hapless family, there is not a single face that does not look like a certified killer.

In the perception of generations that have grown up in independent India, especially those growing up from the 80’s, that is what the Muslim represents and the film is crawling with these mausies, the image of the killer cast in iron. Children are told that Muslims are cruel because they kill to eat, meat eating makes them killers and in the film they are constantly eating meat, they eat huge quantities and they eat like carnivores.

There is a song in the film, shot in the meat market, to the beat of the cleaver chopping through flesh and bone. The montage of carcasses of animals, the cleaver, the face of the butcher, the harassed hero, cleaver, chunk of meat, hero, butcher, cleaver, on and on, all cut to the fast tattoo of the cleaver hitting the chopping block. Meat – Muslim – Mayhem. Stereotype becomes reality.

Aside from the apparent pitch about the innocent victims being sucked in by Islamic terror that might create momentary sympathy among the viewers, aided by the fact that Aamir is an ‘outsider’. A doctor (who couldn’t have gone to a madrasa, he does not have a beard and dresses up ‘defferently’) and a person like “us”, he doesn’t even look like a Muslim. Pray what does a Muslim look like?

Did Dilip Kumar, Mohammad Rafi, Sahir, Kaifi, Majrooh, Johnny Walker, Ajit, Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Waheeda, Zeenat Aman and Naushad look like Muslims? Do Shabana, Farookh Sheikh, Javed Akhtar, Aamir, Shah Rukh, Salman, Irfan look like one?

The major argument of the film feeds upon and justifies the stereotypes about the Muslims being projected by the majoritarian discourse. The majoritarian discourse has propagated this for a long time, but its adaption by cinema, especially, the so called thinking cinema, is the most worrying part about the film. The other part that worried me greatly about the film was what I began with, the appreciation that the film received among both the viewers and the critics.

The communal profiling, the condemnation of an entire community, the branding of every Muslim as a terrorist, the refusal to see Muslims as ordinary people and to portray them as lowlife that began with films like Parinda and was carried on through Border and Sarfarosh and others of the ilk has come full circle.

This is nothing new; the precedent for this was set by Leni Reifenstahl and others in Nazi Germany. The ‘other’ in the Europe of the 1930s was the Jew, the other in the first decade of the 21st century are the ‘mausies’, not only in India but all over the world, including among the survivors of the holocaust.

There is a difference though; Delhi 6 is also being made. For more on that, wait for the next piece, appearing in these columns, shortly.

I am one of those who liked Aamir but somehow never got the feeling that the director was interested in exposing the ‘network of terror’ that exists in ‘Muslim ghettos’. The points you have raised are very valid and make me want to see Delhi 6. But it is about representation and a perception of that representation.

Aamir as a character was eulogized at the end with that song ‘Ek lau kyon bujhi…’ and that was a big problem; but at the same time, there were snatches of TV News reporting how a ‘terrorist’ had blown himself up. Therein, I thought was something to salvage from the film. It came full circle — from the inspector at the airport suspecting this guy to be a terrorist to his being condemned as one after his ‘sacrificial’ death.

So, in that sense, the film to me portrayed a kind of entrapment for the Indian Muslim — he/she just has no way out. The choice is between terrorism and exile.

The shots that you emphasized about meat, the public toilets, dirty narrow lanes, etc., are very realistic — one doesn’t really feel overwhelmed by them nor do they exude any ‘Muslim-ness’. I felt it was a tour for all elite people, not just Muslim ones, into a community’s marginalized life. How both realities exist in the same city (Aamir had returned to practise in Bombay) without coming face to face.

So, while the orthodox Hindu imagination about meat may be a problem, but to in fact show it unabashedly and realistically, was to me different from filtering it through *any* sensibility — neither a demonizing one, nor a ‘sensitive’/protective one.

Of course, this is contentious because everything is filtered; nevertheless, it was more towards realism according to me. In fact, rarely in popular Hindi films do we see people eat meat (or even eat for that matter). All the biological acts of the body are brought into focus in the film. (We’ll have to wait for another film by this director, where there may be scenes of eating meals, to know how bigoted he may be.)

In fact that scene when Aamir emerges out of a PCO after making a call to Pakistan and is chased by a policeman (who is prompted by the PCO woman), is a confusing and interesting scene. I still do not know whether the policeman chased him because he, along with the woman, wanted to assist the ‘terror network’ by exhausting Aamir further;

or that because he knew Aamir had made a call to Pakistan. The film does not make it clear, thereby not letting off the police so easily.

I would say a Simi Grewal looking down from a multi-storey building to condemn the ‘Paki slums’ which breed terror in the country and a camera (and the protagonist) going into this ‘polluted’ & ‘polluting’ space to show it for what it is, and subject the protagonist to its filth, therein the audience too who are identifying with him, are two very different things. The latter is not about exposing the ‘network of terror’ because the others may be doing things under pressure like him (for e.g. the use of the prostitute in this regard is significant, because she cannot really have much choice in the matter). The theme of entrapment again.

As for the examples of ‘un-Muslim looking’ people that you have taken, mind that they are all public personalities or celebrities. You forgot to mention Sania Mirza. So, there are a few celebrities who do not wear or display items of their identity but for each one of them, there are so many others who do.

Even if it is bangles for most women, sindoor for Hindu wives, janeyu for Brahmin men, henna-ed beards for Muslim men, or a headscarf for Muslim women. To show all that is not a problem by itself. Again, it’s about how one is perceiving the director’s representation.

And yes, this Aamir guy was actually one of those Muslim men, like in your examples of high-profile people, who had shed the obvious items of his ‘identity’. But so had the terrorist boss who was instructing him throughout.

I doubt if you can put Parinda, Border, Sarfarosh and this film all in the same bag. Sarfarosh had that binary which this film can be accused of having, but I would contest it. Sf was a regular, run of the mill popular film and Border was all in all bigoted.

But the kind of realism this film has — for instance, when Aamir dreams about his family being killed by this terrorist boss, he cannot see his face, because he has actually never seen him. I do not want to merely eulogize the realism but argue that it is that which would make people uncomfortable.

So, while I agree that it has its problems as a capitalist, nationalistic film, its portrayal of the ghettoized life actually exposes most of the audiences’ distance from the latter. Therein comes the problem of representation. What would you say about Slumdog and would you compare the two?

LikeLike

that was brilliant, sohail

and very [painful reading

scope for a book

god bless you

john dayal

Ooops, forgot have mentioned great post! Waiting for your next one!

LikeLike

Dear Dr Dayal,

Kindly do see my response to this blog post further down the comment thread.

tks

LikeLike

very well written.

would not contest on any issue.

but will go back and watch the film again.

kaniz

LikeLike

Sohail, bahut umda. Haven’t seen the film though but could exaclty visualize the scenario. Meanwhile, did see Delhi 6 and look forward to reading your take on it.

LikeLike

In response to Sanya At no pint in my piece did i have the intention of suggesting that there is a network of terror existing in Muslim Ghettoes, quite to the contrary, there isn’t, but that is my point. The film makes a strong point in favour of the assertion that it is here that the network of terror exists. The minute to minute reporting to the boss-man about each and every movement of the man on the run, relayed as it is through the eyes and ears of the network establishes just that.

Look at the faces, believe you me, this assembly of crooks is not a mere accident, and neither is the constant focus on meat eating. Their is a systematic propaganda about the inherent blood thirstiness of Muslims that originates in their killing of animals to fill their tummies, the opposite of course is the myth that vegetarians are peace loving by nature. So i insist that this focus on meat both cooked and raw is not realistic but surrealistic and intentional to reinforce a stereo type

And finally I do not think Muslims look like this or that. Does A.R.Rehman Look Like a Muslim does Sania Mirza? What do Muslims look like? We have created an image “Beard, Kurta or Banyan, Skull Cap, Lungi or Aligarhi Pajama, Amulet”. Shall we say DAVP has created this image in their Unity in diversity Posters.

Every Muslim in the film looks like A DAVP hoarding caricature of a Muslim. Except of course the Hero who dies for the nation. Every muslim in the film is part of the network, except of course the hero and that is why he has to die. All good muslims are dead. Those that remain are all terrorists. That is what the film says to me. And that is my problem with it.

My other problem and that is bigger than the first is that it is a very well crafted film. it is not meant for the “masses” as the cine fraternity expression goes. It is meant for the “classes” to borrow one more phrase from Bombay Cinema. The film was released primarily in Multiplexes. This is where people go after reading film reviews these are the people who are supposed to be the enlightened liberal middle class intelligentsia and it is these who liked the film and that is what is worrying the living daylights out of me. I am scared. really scared. Because if people like “us” also accept this representation of the ‘Other” then we are in trouble. Real serious trouble

LikeLike

I agree with the some of the comments that Sanya has made above. I also watched the film, particularly with the intention of trying to understand its gross and subtle themes. While I agree with the facts you have stated in terms of what the film shows (the dirty chawls, the excessive indulgence in non vegetarian food etc) I don’t agree with your analysis of the film in that I think there is much more to what the director tries to communicate other than reiterate existing stereotypes about muslims in India. I think it does well to highlight the complexities and conflicts that an urban, educated muslim might have to grapple with vis a vis trying to break away from the stereotypes while trying to identify with his “community” of which he is repeatedly reminded he is a part. This brings to my mind incidents from my own life where Muslims are reluctant to admit that they are religious, because in recent times being religious and being contemporary and literate have ceased to be compatible with each other in the perception of the general public. This is a shame indeed. I think it captures that conflict very well.

Also, the repeated reminders from the man on the phone as to what Aamir’s roots are, and what “his people” are suffering in their country have a stark similarity to political strategies used by parties who pretend to protect the interests of the oppressed / minorities while constantly reminding them that they are the minority. Sort of like doing a slow dance with the communities in question, done with the alleged intention of including them into the larger system, but the tunes and beats to which it is done serve only to remind the same communities of their inferior status. Rather than trying to empower them, these political games serve to use empowerment as a ploy to get their votes. A ploy that exploits while it pretends to empower, because it is dependent on the minorities staying just where they are.

What emerged as a stronger theme for me was not the image of muslims as dirty and evil people but rather the image of a muslim who has broken away from that stereotype and tries to remain firm in his resolve to NOT get sucked into the web of terror that seduces him.

It showcases a struggle between individual identity and the identity of the community to which one belongs and how there is little room for liberalism and personal freedom when the latter forces are as powerful as they are.

I think the ending was also well done, and personally I did wonder why Aamir had to die with the bomb instead of just tossing it in the ditch and making a run for it. I concluded that it was perhaps to leave the viewer with questions that warrant deep reflections about the viewer’s own identities, and their struggles to remain “individual” in significant ways while being part of a larger community. The death of Aamir leads one to wonder where the answer lies and what it lies in. It might seem a hopeless struggle with no answer in sight, with the only apparent options being to either destroy oneself or destroy the other. But the subtle message I got from it was that in destroying himself, Aamir became the hero that he did not because he saved the lives of those on the bus, but more so because while being part of a certain community, he remained true to his individual principles and stood his ground till his last breath.

I am not religious and think of myself as an atheist. I have personally gone through struggles of certain religious or social identities being imposed on me that I want no part of. I think this is why I understood the movie in the ways that I did.

We all understand films and other art forms largely based on what we bring to it from our own psyches and world views. The film does not speak to us in a language that we do not already understand. I think our interpretations of it tell us more about ourselves and our own conflicts than the world “out there” which has little existence independent of the world inside us.

I guess it is a matter of perspective and how you look at it. I am just offering an alternative interpretation, without intending to devalue yours.

LikeLike

Wonderful article. I haven’t seen the film but your descriptions were vivid enough for me to imagine what you’re saying. Look forward to reading your take on Delhi 6.

LikeLike

I have not yet watched ‘Aamir’ and hence not qualified to comment, though, notwithstanding the merit or otherwise of the critique, I feel impelled to share my impressions on the subject. But a timely word of caution first! Critique of works do not necessarily amount to doubting the intention of the maker.

The Muslim character in our films has never been really realistic. In the films of the fifties till as late as Sholay, the Muslim character, almost by definition, was always extra good. He would be the one designed to break the barriers, defy audience expectations and establish his or her essential goodness, perhaps depicting the desire of the maker to dispel a notion or two about the Muslim. And filmmakers of the fifties onwards depicted the Muslims, patronizingly though, in a larger than life image. No bad Muslim guys. No Muslim villains and vamps. Only the good Muslim neighbour or servant or friend ad infinitum. And this scenario continued till quite late, almost as late as the seventies.

Things, however, changed slowly and rather imperceptibly. Coinciding almost with the ascendancy of hard core Hinduvatva and during the time Mumbai was ruled, post Ayodhya/Mumbai Riot/Blast,by Shiv Sena in Mumbai and its co brothers at other places, the Muslim character metamorphosed slowly first and quite brazenly later. We suddenly had films full of villains , menacingly built and remorselessly vile and cruel, brandishing their Muslim identities to meet an equally cruel end. Initiating a shocking depiction of Muslims in the context of Mumbai film industry’s history, this vision later came to be watered down with judicious inter mixing of equally corrupt and vile non Muslim characters too. This negative Muslim depiction had to have its final charade when Trackeray at the height of his power dictated changes/ editing in ‘Bombay’ of Mani Ratnam fame. Well meaning though the director may have been, what emerges out in the film was the demonisation of a community which was itself largely a victim during the Mumbai riots, though the abundance of skull capped rioters left no illusion as to who these rioters actually were.

The point,however, is not limited to Muslim alone or that of the indian muslim. The depiction of blacks in popular Hollywood films till the other day smacked of the same stereo typing.The larger point is demonisation of the ‘other’or as Sohail Hashmi puts the slow poisioning of minds and perceptions, which in their full bloom lead to holcausts of variable degrees at different points of time.Rome after all was not built in day!

LikeLike

This was a great article an I was thinking in the same line after watching the movie.

Anyway, when the terrorist had to kidnap the family and force somebody to do the explosion job, then why on earth they would not choose somebody randomly (hindu or sikh) why only a muslim guy!!! ( just later to convince him hard that he has to do it !!!)

I am sure if the there would be any other guy of any religion instead of Amir would have reacted like a ‘normal’ muslim.

thought I like the muslim guy role in “Mumbai meri jaan” quite touching!!

LikeLike

Hi Sohail

Couldn’t agree with your more. Was quite revolted and angry at this stereotyping of the Muslim, right through the film. But is was done just a little more discretely in Mani Ratnam’s “Bombay” too. Hindu father carries a harmless umbrella while Muslim father is always seen with his meat chopper… and other such images. Of course Aamir, which pretends to be pro-the decent Muslim, can only do that against the backdrop of the majority of the community who are unshaved (and so unclean!), gluttonous meat eaters, who are all on the side of the terrorists.

I wish you had written this piece earlier.

Jennifer Mirza

LikeLike

Reading Sohail and the debate here brought back to memory a critical review of Aamir that Shohini Ghosh had written last year.

Shohini had said: “The profound irony of Aamir is that it depicts the innocent Muslim as being terrorised by his own community. If the filmmaker’s intention was to acknowledge innocent victims like Dr Mohamed Haneef, who was falsely accused by the Australian government of abetting the Glasgow terror attack, then all that remains is the stench of burnt good intentions. The irony is no less underscored by the fact that the last decade has witnessed the rise of the Hindu Right along with an acceleration in hate crimes, including the horrifying genocide in Gujarat. Aamir’s proposition that Muslims are oppressed by their own community is a complete disavowal of history, circumstance and the testimony of brute fact.”

Read the whole review here.

LikeLike

Did Dilip Kumar, Mohammad Rafi, Sahir, Kaifi, Majrooh, Johnny Walker, Ajit, Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Waheeda, Zeenat Aman and Naushad look like Muslims? Do Shabana, Farookh Sheikh, Javed Akhtar, Aamir, Shah Rukh, Salman, Irfan look like one?

Just wanted to understand who makes the decision as to what a muslim should look like. Is it a crime to have a beard, wear a pyjama and a cap and to appreciate a well crafted movie like Aamir …oh and for the specific reasons mentioned in the post…..Why are just the above and only the names that are given celebrity status be a benchmark as to what a muslim should look like……why can’t a mufti from a masjid be a role model…….just my question though….

LikeLike

precisely my point dear reelgenius,

no one has a right to decide what a muslim looks like, for that matter what do hindus look like or christians.

How does your faith decide your look. what would happen to someone,who converts to another religion will S/he begin to look different. The so called denominational attributes like beard, a top knot or long hair are not faith specific and neither are our attires, all clothes stitched or otherwise are non-denominational.

it certainly is not a crime to keep a beard or wear a payejaama or a cap, my protest is in showing muslims in specific dresses and a specific kind of beard, and to do it to the almost total exclusion of any other depiction. This portrayal suggests that all muslims look like this alone and if they look different they are not muslims.

As for the reason for choosing the above names, the choice is delibrate. none of these fit the stereotype that has been prepared for the Indian muslim and yet they are among the most well known muslim faces in India.

I am not suggessting that they are a bench mark for what muslims should look like. How can any one decide how a specific community should look like. Hitler tried some genetic engineering to achieve a uniformity of appearence among the German Aryans as he called them. We all know the sticky end he came to and the devastation, his desire to breed a race of rulers, wrought upon this world.

As for role models. I am not suggesting any, I would personally not be inclined to chose for myself, or suggest to any one ready to listen to me, to take as a role model any of the gentlemen who make a living out of other peoples faiths. but if someone decides to make such a choice, who am i to prevent them and yet you can’t expect me to support them and should not object if i choose to distance myself from them and their perceptors.

LikeLike

I do not believe that anyone who has a pair of fully functionng eyes can deny the overall presence of meat in this film. muslim meat, big meat, fresh meat, bloody, dead meat… meat galore. thats #1. #2 stereotypes abound from unkempt wild beards to evil beady little eyes and the ever present muslim malice. #3 if the purpose of the film is in exposing the complexities of “life” and choice for the indian muslim man, why is everything centered around consumption, insatiable blood thirsty hunger, and death? this character is brought to life in the film by an aura of unavoidable doom- the doom that later kills him and he is the only muslim who does not appear to look like all the “others” and yet he ends up just like “them” let’s be real shall we? this type of film, regardless of varying angles of interpretation, perpetuates images, fear, stereotypes, ignorance and an overwhelming sense of hopelessness. the man was doomed from the beginning. what’s the tragedy for him? according to this film- that he was , is, and always be a big bad muslim no matter what he does. that this was somehow meant to shed light on the ignorant views many have of muslims by demonstrating the errors of assumption, though i find poor support of that idea, is in itself niave because of the unbalanced, super one sided, EMPHASIS on everything stereotypically “muslim” and inherantly bad. if he walked around fruit markets, chewing on salads and greens, surrounded by every holy hindu, slum ridden, caste saturated, overly passive stereotype- would you notice the emphasis?

p.s. salad anyone???

LikeLike

Interesting !

It would never have occurred to me to contrast Aamir with Delhi 6 (Thanks Sohail for writing this). Somewhere in my mind, I associated Aamir with what I regard as a new genre of slick flicks on ‘THE NETWORK’ …lurking in the dark… ready to sink its fangs into …unsuspecting ‘good’ Muslims. (Khuda ke liye and Shoot at Sight are great examples of that genre – both, in part, gaining their ‘authenticity’ thanks to the lore and style of Naseeruddin Shah’s performance.) Of course, in the end, always, the good muslim redeems himself by paying a very dear price. I suppose the take home message is that Muslims have no option but to pay such a price to prove themselves to be worthy citizens. Be afraid, very afraid…, the network has taken shape, away from all prying eyes, away from light, and is waiting to strike through slum lords, gangs, neighborhood telephone booth operators, obscurantist preachers, cousins and uncles and just about anyone on earth. Foreshadows of this theme can be traced in films like shall we say Fiza ? What is different now is the boldness of the statement “Your ‘community’ is your real enemy because it conceals all sorts of vipers.”

That is how I read all these films — of course with variations each time. They are successful precisely because they are fundamentally about lulling one’s senses and giving messages stripped out of all context. And dangerous precisely for that reason.

LikeLike

Sohail Hashmi’s analysis turns to the world around the figure rather than focus on the figure itself quite legitimately. That’s where the uncanny dimension of cinema usually lies. The new mainstream cinema has assimilated a realist energy that has turned urban spaces, especially cities like Bombay, into a teeming, tactile world often presented for its own sake. There is an interesting history to this realist assimilation happening over the last two decades, almost exactly paralleling the career of economic liberalization in India. Gradually, the setting – for instance the streets and lanes, chawls, stations and markets in Bombay – has gained an autonomy. It is no longer a setting to an action; it is landscape in the real sense, a sensate, symbolic thing. There are now films which use the density and concreteness of the space, an intensified ‘slice of life’ of the old realism, without much narrative necessity, for its own sake, as if to present a thickness of the habitat that simmers with the pleasure of recognition, familiarity. To a stranger travelling down the quarters of Bombay today the signs of a place evoke a captivating sense of recognition, which one has imbibed from the cinema. This was not true of the earlier history of the industry.

What is so disturbing about Aamir, and what Sohail and others have already hinted at, is that the unfolding of the Muslim surroundings draws upon this representational energy of the industry to present a relentlessly unfolding community life that stands apart and watches on. That’s where the uncanny usually stem from – when the surroundings watch us rather than we watch them. Parallel to the man-on- the-run progression this is the other spread that takes in more and more of the life of a community – more area, more dwellings, more faces, trades. It becomes complete when everyone, even the poorest of the poor, betrays the hero. It is a world that was never busy with itself, as we realize, it was watching the hero. Aamir achieves something rare, willingly or not. By staging a tussle between a sinister watchful landscape and the eye of the consensus – the spectator’s eye – it ends up presenting a case for pervasive surveillance in reverse. There is a breathing organic surveillance of a community united by an obscene bond- an eye written all over. It invites organized, total surveillance from US.

LikeLike

Whatever happened to the promised piece on D6?

LikeLike

Two things one must never do

1)predict the results of an election and 2) promise to write a sequel

The former i have never indulged in, having known that the process would culminate with egg on my face and so i left it for those who like egg on their faces while being watched by millions on TV

Unfortunately, i did not realise that promising a sequel that i fail to deliver will also lead to similar consequences. Thankfully the audience is considerably smaller, though the embarresment is not. I am not going to make another promise, but the congealed yellow of the egg is not a pleasing sight so some thing will have to be done and soon

LikeLike

No pressure Sohail. I found your piece on Aamir very thoughtful and was eager to read the ‘sequel’ on D6, the latter a much needlessly maligned film in my view. My thoughts on it here:

LikeLike

Am foursquare against any perpetuation of stereotypes that can harm the cause of harmony, and therefore pay special attention to high-risk instances and make it a point to protest stereotypes of vulnerable minorities.

However, am willing to give Aamer the benefit of doubt. In my view, the film’s intent is to disturb the complacent, and question the cosy assumption of a potential escape from grim reality by showing how your destiny cannot be your free call so long as there is acute misery in the world.

The film is aimed, methinks, at a sophisticated audience, the sort who need to recognise that apathy could perhaps be an untenable attitude to adopt whilst injustice persists. What comes across is the sense of seige rather than the diet preferences etc, and it evokes the sort of empathy that few films have in recent times.

The plot etc is supposed to be bizarre (as in fiction), in the this-could-happen-to-you genre of crazy Lewis Carollesque circumstances, and clearly not to be taken as a this-happens-all-the-time portrayal.

Yeah, the last scene could’ve had shut-eyed Aamer moving his lips (as an indication perhaps of his “succumbing” to the reality of his “identity” tag, unfortunate as it would be).

On the whole, such efforts need not be discouraged, even if the props could be secularised as you suggest, just in case some viewers get the wrong picture.

LikeLike