On the morning of the Games, what should many of us — who have dissented against them in different ways and forms — make of our dissent?

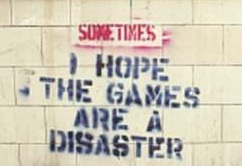

Let me begin with a confession. I am one of the authors of this graffiti that dots some of South Delhi and, ironically, remains on the wall opposite the main entrance of the JLN stadium, though now its probably hidden under a hoarding of Shera who appears to be not nearly as endangered as his real life inspiration:

It was a few months ago when the Games fervour was just beginning. The magnitude of all that they would become hadn’t quite sunk in. The graffiti felt, at that time, like a momentary defiance that opened up some space to breathe in a city where the deafening and deadening drum rolls that precede any spectacle were inching closer. You could hear them. You could tell that soon little else would be audible.

The colours aren’t a stylistic choice. The first version didn’t have the red-lettered “Sometimes”; it just read “I hope the Games are a Disaster.” When I saw that first version of the stencil, it made me stop. That moment of hesitation is what is these days loosely called “Pride.” It’s hard – even when you can theoretically, politically and logically fully demolish the idea of the nation, the city and this false pride — to spray permanent paint on such words in your own city which you love even when you hate. Some would say that I lack the courage of my convictions. Perhaps they are right.

But today, the reason for my hesitancy seems different. It came from knowing that I didn’t actually care about the Games being a disaster. I don’t want the Games to fail. I don’t because their failure will do nothing to move us towards being a city that would not have bid for the Games in the first place. A city where urban politics, institutions and actors would get why this was so and where the answer would have nothing to do either with questions of our capacity to handle programmes of scale or with the corruption and mis-management that actually occured.

Even the initial budget for the Games was nearly Rs 900 cr. It currently stands at over Rs 2300 cr and will most likely rise. By some estimates, it is nearly ten or twenty times this amount depending on what you count. But even if you take the lower figure, that’s one and a half times the entire budget for low-income housing in Delhi under the Rajiv Awas Yojana. One and half times the budget for water and sanitation. Twice the allocation for health. In fact, the eventual cost of ‘streetscaping’ alone – at Rs 1,000 cr – is just under Delhi’s annual budget for education in 2010. In the Games as they stand, streetscaping and education sit on nearly equivalent budget lines without a trace of irony.

How did a city with such entrenched inequality get to the point where it chose to invest resources of this magnitude into infrastructure so disconnected with the needs of its citizens? And this is not an argument just for the needs for the poor. What is remarkable in Indian cities, still, is that the quality of life and infrastructure for a large number of the non-poor also remains uncertain, ad-hoc and deeply insecure. Outside a small, very elite minority of the city, our infrastructure systems fail all of us. For some of us, the result is discomfort. For many, it is the erosion and eradication of life itself. Yet outside the new buses and the Metro – both projects sanctioned and imagined before the Games – almost none of the new infrastructure will dent the city’s actual needs to allow its residents to live with dignity.

The answer partly lies in the current common sense that surrounds “urban development,” a story is being spun around a notion of growth and development that, for the first time in independent India, centres squarely around the city, drawing from the city just as it re-shapes it. Urban development in the first three decades of the nation was incidental — India lived in its villages. Now as Manmohan Singh said at the inauguration of the JNNURM — which will exponentially outlast, outspend, out-everything the Games — “though there is no doubt that India still by and large lives in its villages… urbanisation is a relentless process which has come to stay and has to be factored into all our developmental thinking and development processes.”

The spectacle of the mega-event is one symptom of the story that has been told of this urbanisation that has “come to stay.” That the city in India [with some exceptions] emerged politically and economically in a particular global politico-economic climate is not insignficant. Last night I was driving around the new Delhi. As I turned onto Nehru Stadium road, there was another public. Cars and bikes stood parked and dozens of people gathered, milling about, taking pictures with the stadium in the background. On any other day, this would have been India Gate. Today, it was a flyover in front of a stadium. This is one image of urban development – technical, infrastructural, planned and modern — created by and catering to a certain circulation of global capital. And it is compelling both to those families and to many of us particularly because our cities have largely known only infrastructural absences. The JNNURM imagines the city in very much the same way — as a site to be made anew with financial, technological and infrastructural answers to what are deeply political questions of governance, resource allocation, urban priorities and rights/entitlements.

Any dissent we articulate has to engage with the families on the flyover and the capital/policies that lie within their viewfinders. It has to engage with what has drawn these families there, to acknowledge that the images they see are compelling to them and to us and yet to challenge them, contextualise them and re-politicise them. This imagination and its corresponding realities of one type of progress, development, wealth and change – a story of a particular kind of urban development –have become exceedingly powerful in the contemporary moment, riding on the coat-tails of the Games while simultaneously propelling them on. It is this imagination of the city that has made dissent against evictions, urban renewal, economic restructuring and the World-Class City nearly impossible in contemporary Indian cities. It is this imagination that has led us to the Games. This imagination is built both on a new political economy of land values, capital and investment coupled with a shifting employment and livelihood profile for the city as well as an aspirational and aesthetic imagination that draws the camera to the lights of the stadium just as it flattens the slum into an image without history, context, or indeed, people.

This imagination is bigger than the Games. From an excellent article by Veronique Dupont in EPW, watch the watch two peaks of slum demolitions in Delhi:

Dupont, V (2008) Slum Demolitions in Delhi since the 1990s: An Appraisal, in EPW, July 12, 2008.

The peaks for number of demolition sites [the line graph] are around 1999-2001 [as Dupont reminds us, Jagmohan was well ensconsed then] and then in 2006-07 – I know that this only scaled further in 2008 and the years hence and peaks again this past year in direct evictions for the Games, the latest of which includes the jhuggies opposite the Leela Kempinski hotel near INA and just off Africa Avenue. In 1996, the Courts did not need the Games to order all “polluting industries” to be closed and relocated in Delhi without truly ever accounting for the loss of livelihoods this would entail. In 1999, Jagmohan’s Yamuna Beautification Plans didn’t need the Games to argue for the merciless evictions he was so proud of. The poor have been erased from this city long before the Games and often much more forcefully. The assent to those moments also occurred in our names, well before the Games, and moments like these will come again – for the next flyover, the next park, the next mall, the next district complex, and indeed for the next Games.

How do we counter this imagination? How do we urbanise our dissent, our political frames? What is the vision of the city that brings together concerns of inclusion, shelter, work and pleasure — socially, economically, politically and spatially? What is – put provocatively — a new vision of progressive politics that centres on the city and not the factory?

These Games will pass. Their grand plans have not and cannot erase and re-make this city. But the larger story of urban development they represent is attempting to do partly this. Our dissent and defiance has to translate and scale to respond to this story of urban development by offering another urban imagination. It is an imagination that has to translate and appeal to the realpolitik of government, business, resident association and movement alike as well as to the bastis, resettlement colonies, RWAs, newspaper offices as well as to the families on the flyover. It doesn’t have to be universally loved but it has to survive within all of these spaces. It has to fight for the some foothold in each, make some claim to be part of the common sense that pervades these institutions. It is only then that it can pervade both the plans that are made along the ways in which everyday life and people will undo these plans. It is only then it can creep into budget lines, policies, and programmes.

The leader of the Zapatistas, Sub-Commondante Marcos, often wrote long hand-written letters from the forest that he sent to the media. It struck many as odd that the leader of an armed insurgence would pick up the pen as often as his gun. When asked one day why he did so, he replied: “Ideas are also weapons.”

Indeed they are and, on the day of the Opening Ceremony of the Games, it is time we picked up ours.

Couldn’t agree more.

LikeLike

I think this is a wonderful preface, a making way, a demand. Now that extra leg of work: What would be some of the salient points of this new vision, this new urban imagination? Even tentatively, could you list out a few? What would it look like? For instance, picking one idea up, how does it understand ‘urban infrastructure’, what concrete list of priorities does this new imagination make in relation to this infrastructure?

LikeLike

Dear CitySlut,

I apologise for taking so long to reply to your question – life got in the way yet again. I hope you get to see this and we can pick up this thread.

I think there are precedents for this kind of rethinking already alive in the world. Take Brazil’s City Statute 2002. By changing federal law, Brazil made all cities and towns re-write their Master PLan on the maxim that “property has a social as well as market value.” Now, that would alter our cities radically in their form. This language is present in our own history: Justices Krishna Iyer in the 90s ruled in favour of agrarian land reform citing “the social value and function of land.” This could be the basis of a significant re-imagining.

A second fight would be on questions of public interest. With that kind of maxim, how you value different kinds of uses of public land would change immensely. You could never, for example, evict Yamuna Pushta to make a riverside promenade if housing counted high on the priority list of public interest. If we take the Land Acquisition Act and trace how its been used, to claim what land, and in what public interest, then generating a significant urban discourse on what public interest should look like and what the courts should use as a barometer in deliberating on Public Interest Litigations would be a huge first step. How do we get to such a dialogue? In what spaces will it circulate most effectively?

A third platform/perspective that has to come in is one of priority. Too often, debates on public interest get into a mess that reduces them to different interest groups and their notion of the public. This evades the question of hard decisions on priorities. The Delhi Master Plan 2021, for example, doesnt just mandate building low income housing, resettling the poor in the same or proximate zone, it also has a priority ranking of what work will get done first and it envisages that low income housing must be built before other directives in its plans. This priority has been lost in readings of the plans both by planners as well as the Courts.

Priorities can be legally as well as politically advocated for. The South african constitutional court, in a landmark ruling on housing, ruled that any housing policy that did not cater first to the needs of the most vulnerable was not “reasonable.” That word “reasonable” has deep policy and legal resonance and is used deliberately by the court. But it also worked, to an extend, in South Africa because of the political climate of building a new, post-apartheid nation with a new constitution. Can we create a new multi-stakeholder political climate here? As long as Bhagidari remains limited to only planned, middle and upper middle class neighborhoods, the answer is no. Pushing Bhagidari to recognise unauthorised colonies, however, would drastically change the possibilities within that space.

With these precepts, lets think of infrastructure. A legally and politically “reasonable” infrastructure policy would then have to justify its expenditure on how it caters to the poorest. Water and sanitation would take priority over flyovers. the BRT — redesigned and done better than the pilot — would take priority over the Metro. Land Acquisition would have to be taken to build services in the peripheries rather than simply acquire land for development zones. The measure of the City’s development would be the minimum amount of water supplied at a household and individual level rather than at the zonal level. Distribution issues would take precedence over generation ones.

Do you see where I’m headed with this? One could build an accounting and budgeting system that factored in other kinds of value, project by project. The Gender Budgeting systems are a brilliant example of this – of how standard cost figures transform when seen from particular perspectives.

but these all depend on creating institutional, public and discursive spaces where these debates can occur. That’s the question facing us: what are these spaces? which exist already and which have to be created? who can/should/must create them?

cheers,

Gautam

LikeLike

The problem is not in urban centres..the problem is in not having enough. When we have an alternative plan to megacities, when we allow suburban cities, district towns to grow the problem of slums will also go and enough capital will circulate in the hinterlands even after regularized corruption to fuel regional growths.

LikeLike

Dear DirtRoad,

I agree with this to an extent – we have not thought in terms of regional development and the development of secondary towns that deflect some of the migration of our major urban centres. my only caution while that must occur, our urban centres cannot reverse the reality of contemporary migration and given that this migration is a matter of right — moral, ethical, and legal — for migrants, existing metropolitan centres have to prepare for these migrants even as more diversified urbanisation occurs.

cheers,

gautam

LikeLike

Perhaps, we could begin, picking up ‘Ideas’ as weapons, by drawing on our imaginations to propose an alternative imagination of what the city’s space is about. I, for instance, have dreams about demolishing the wasteful planning/architectural monstrosity called the ‘Lutyens Bungalow Zone’ , or the ‘diplomatic enclave’ of Chanakyari and replacing these with mixed use, mixed occupation high and low rise neighbourhoods designed with architectural flair. Imagine how the acres of space freed up by the demolition of elite enclaves in Central Delhi could usher in an architectural renaissance. The vision of a bulldozer demolishing 10 Janpath is to my minds a very pleasing thought.

LikeLike

Sigh – you’re in the heart of it here, Shuddha. If I could tell you

how many excellent draft plans — from radical surgeries to gentle,

more politically palatable adjustments — I have seen that would

re-make Chanakyapuri and Central Delhi to density levels that aren’t

as appaling as they currently are….

But there is a battle closer to hand: the Supreme Court has been playing

with the DDA in clearing two huge land acquisitions. They are of the order

of 30,000 acres or so — think two new Dwarka’s. How these get used

needs to be the focus of sustained in-system and activist pressure – they

are threatening to create a second embassy area in one of the two. This,

given the transformation using these for low income housing could create.

It is a long way off, yet – they have to reclaim the land not from the poor

but the rich, so the chances of it happening, even the DDA admits, are “difficult

in the near future,” as their senior planners put it :)

LikeLike

Gautam while I generally agree with you, I just want to point out that the CWG is being hosted not just by Delhi but India; it is not just Dilli but Hindustan that is on display. Delhi already has a lot invested in it as a city, and the rest of urban (and rural) India is wondering when they will host such events that will provide an opportunity for such debate about the cities, towns, kasbas and villages they call home. My point is that the resistance should not replicate the Delhi-centricism of the establishment :) The very fact that Delhi gets to host the Asiad and then the CWG, which despite their problems do end up with investment in infrastructure, is only one of the symptoms of the larger problem of Delhi-NCR-focused development. You want to do something? Go to Delhi or Bombay. That has to change. The money invested in CWG is not just Delhi’s. In fact, it’s not Delhi’s at all.

LikeLike