Amnesty International has released a report calling on India to repeal the Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act. The report, called A ‘Lawless Law’: Detentions Under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, can be downloaded here. Given below is the text of the Introduction and Summary of the report.

‘We have to keep some people out of circulation…’ – Samuel Verghese, (then) Financial Commissioner – Home, Jammu and Kashmir in a meeting with Amnesty International, Srinagar, 20 May 2010

Shabir Ahmad Shah has been kept “out of circulation” and in and out of prison for much of the time since 1989, when a popular movement and armed uprising for independence began in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). As the leader of the Jammu and Kashmir Democratic Freedom Party he has been amongst the most vocal and consistent voices demanding an independent Kashmir. As a result he has spent over 25 years in various prisons, much of it in “preventive” or administrative detention, that is, detention by executive order without charge or trial.1 His incarceration has been solely for peacefully expressing his political views. Shah was last released from prison on 3 November 2010 but since that time has been subject to periods of arbitrary house arrest.

At the time of Amnesty International’s visit to Srinagar, the capital of J&K, in May 2010, Shabir Shah was in prison. Amnesty International was denied permission by the state authorities to meet with him, but was able to meet his wife Dr. Bilqees who said, “His continuing detention is a tactic to break his resistance. The government think that if they keep him away from us and make us all suffer, he will agree to remaining silent. Even though he is concerned about our daughters who rarely see their father, he will not desert his principles.”

Shabir Shah is one of the most high profile of those detained under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978 (PSA) but he is only one among thousands who have been detained without charge or trial in this manner. Estimates of the number detained under the PSA over the past two decades range from 8,000-20,000. This report reveals how the PSA violates India’s international human rights legal obligations. It further provides evidence of the ways in which administrative detention under the PSA continues to be used in J&K to detain individuals for years at a time, without trial, depriving them of human rights protections otherwise applicable in Indian law.

The report is based on research conducted by an Amnesty International team during a visit to Srinagar in May 2010 and subsequent analysis of government and legal documents relating to over 600 individuals detained under the PSA between 2003 and 2010. The research shows that instead of using the institutions, procedures and human rights safeguards of ordinary criminal justice, the authorities are using the PSA to secure the long-term detention of political activists, suspected members or supporters of armed groups and a range of other individuals against whom there is insufficient evidence for a trial or conviction – to keep them “out of circulation.”

The region of Kashmir has been a source of dispute in South Asia for decades. But since 1989, J&K has witnessed an ongoing popular movement and armed uprising for independence. Armed groups regularly carry out attacks on security forces as well as civilians. Amnesty International acknowledges the right, indeed the duty of the state to defend and protect its population from violence. However, this must be done while respecting the human rights of all concerned.

Amnesty International takes no position on the guilt or innocence of those alleged to have committed human rights abuses or recognizably criminal offences. However, everyone must be able to enjoy the full range of human rights guaranteed under national and international law. By using the PSA to incarcerate suspects without adequate evidence, India has not only gravely violated their human rights but also failed in its duty to charge and try such individuals and to punish them if found guilty in a fair trial.

Over the past decade there has been a marked decrease in the overall numbers of members of armed groups operating in J&K. By the J&K Police’s own estimates, only around 500 members of armed groups now operate in the Kashmir valley.2 But in the last five years, there has been a resurgence of street protests. Some of the protesters, most of them young, have resorted to throwing stones at security forces, which have on many occasions retaliated with gunfire using live rounds. Despite this apparent shift in the nature of opposition to the Indian state, there does not appear to be a change in the approach of the J&K authorities. They continue to rely on the extraordinary administrative detention powers of the PSA rather than attempting to charge and try those suspected of committing criminal acts. Between January and September 2010 alone, 322 people were reportedly detained under the PSA.

Many of these individuals may have been detained after being labelled as “anti-national” solely because they support the cause for Kashmiri independence or a merger with Pakistan and because they are challenging the state through political action or peaceful dissent. Some of the political activists detained under the PSA include lawyers and journalists. Besides Shabir Shah, a number of prominent political leaders have been detained under the PSA; many including Masarat Alam Bhat remain in detention.

Amnesty International opposes on principle all systems of administrative detention. The Indian Supreme Court has also described the system of administrative detention as “lawless law”. The PSA has become precisely such a “lawless law”, largely supplanting the regular criminal justice system in J&K. Criminal justice systems have developed procedures, rules of evidence, and the burden and standard of proof in order to minimize the risk of punishing the innocent and to ensure punishment of the guilty. It is unacceptable for any government to circumvent these safeguards by use of “preventive” or any other form of administrative detention: punishing those suspected of committing offences without ever charging or trying them.

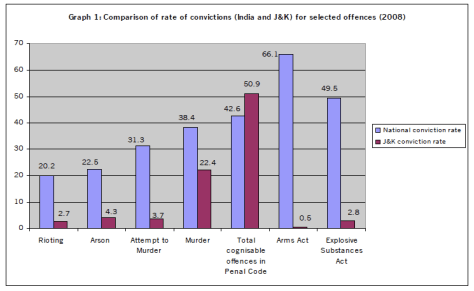

The rate of conviction for possession of unlawful weapons – one of the most common charges brought against alleged supporters or members of armed groups – is 0.5 per 100 cases: over 130 times lower than the national average in India. Similarly the conviction rate for attempt to murder in J&K is eight times lower than the national average, seven times lower for rioting and five times lower for arson (see graph below). In contrast, the number of persons in administrative detention without trial in J&K is 14 times higher than the national average – a possible result of the monthly / quarterly “targets” or quotas of detentions apparently followed by the J&K police.

Many of the people detained under the PSA without charge or trial for periods of two years or more may have committed no recognizably criminal offence at all. Under the PSA, detention can be justified for undefined acts “prejudicial to the security of the State” and for extremely broadly defined acts “prejudicial to the maintenance of public order”. The possibility of detention on such vague and broadly defined allegations violates the principle of legality required by Article 9(1) of the International Covenant on civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which India is a party.

Detainees also cannot challenge the decision to detain them in any meaningful way; there is no provision for judicial review of detention in the PSA; and detainees are not permitted legal representation before the Advisory Board, the executive detaining authority that confirms detention orders. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD), in a November 2008 opinion on 10 PSA cases from J&K, found that the detentions did not conform to the international human rights legal obligations that the Government of India is bound by.

Furthermore, state officials often implement this law in an arbitrary and abusive manner, as numerous cases cited in this report demonstrate. Detaining authorities fail to provide material on which the grounds of detention are based to detainees or their lawyers. Detainees can approach (often successfully) to the High Court to quash their order of detention, but Amnesty International’s research clearly shows that the J&K authorities consistently thwart the High Court’s orders for release by re-detaining individuals under criminal charges and / or issuing further detention orders, thereby securing their continued incarceration. The ultimate decision as to whether PSA detainees are allowed to go free lies with an executive Screening Committee made up of government officials, police and intelligence officials whose deliberations are not open to any public scrutiny.

Systems of administrative detention are notorious for facilitating human rights violations, including incommunicado and illegal detention and torture and other forms of ill-treatment in police and judicial custody. The PSA is no exception. Many of the PSA cases studied by Amnesty International for this report contained evidence of periods of illegal detention in violation of national and international law. Many alleged the use of torture and other forms of ill-treatment in coercing confessions. The PSA provides for immunity from prosecution for officials operating under it, thereby permitting impunity for human rights violations carried out under the law.

Amnesty International has previously called on the Government of India to reform its administrative detention system, as have other international human rights organisations and a number of UN human rights mechanisms. India has so far chosen to ignore such calls. In a meeting with Amnesty International delegates in Srinagar in May 2010, the then Additional Director General of Police (Criminal Investigation Department) of J&K asked, “What rights are you talking about? We are fighting a war – a cross border war.”

Such opinions, and the practices that result (as documented in the current report), run directly counter to legal commitments made by India in ratifying international human rights treaties, and assertions regularly made by government officials at both the state and central level that the rule of law should prevail in J&K. The widespread and abusive use of the “lawless” PSA, far from building confidence amongst the Kashmiri population, further risks undermining the rule of law and reinforcing deeply held perceptions that police and security forces are “above the law.”

Amnesty International calls upon the Government of Jammu and Kashmir to:

– Repeal the PSA and end the system of administrative detention in J&K, charging those suspected of committing criminal acts with recognizably criminal offences and trying them in a court of law with all safeguards for fair trial provided;

– As a means of demonstrating the government’s commitment to the rule of law, end practices of illegal and incommunicado detention and immediately put in place safeguards to ensure that those detained are brought promptly before a magistrate, provided with access to relatives, legal counsel and medical examination, and held in recognized places of detention pending trial.

The Governments of India and Jammu and Kashmir must further:

– Carry out an independent, impartial and comprehensive investigation into all allegations of abuses against detainees and their families, including allegations of torture and other illtreatment, denial of visits and adequate medical care, make its findings public and hold those responsible to account.

Amnesty International urges the Government of India to:

– Extend invitations and facilitate the visits of the UN special procedures including particularly the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

BOX 1: NO WAY OUT

Police arrested Muneer Ahmad Sheikh on 29 July 2008 and charged him with possession of prohibited weapons. While in prison awaiting trial in this case, a PSA detention order was issued on 20 September 2008 (No. DMS/PSA/22/2008). At the same time he was also formally charged in three additional criminal cases of attacks on security forces carried out in 2001, 2004 and 2009 respectively. The PSA detention order was quashed by the High Court on 4 August 2009, which accepted his habeas corpus petition (HCP 240/09). Sheikh was granted bail in connection with the initial charge of possession of prohibited weapons in January 2010, but he remained in detention awaiting trial on the other charges.

On 24 February 2010, the trial court dismissed two of the three outstanding charges against Sheikh noting that the only evidence against him was a confession made by him while in police custody which was inadmissible in court (in India, confessions made to the police are inadmissible as evidence because of fears that they may be coerced). Sheikh’s lawyers claim that he was indeed tortured by police during his interrogation. The court dismissed the third charge against Sheikh on 15 March 2010.

Despite having no further criminal charges or PSA detention orders pending against him, the prison authorities handed Sheikh to the police on 16 March who detained him illegally at the Joint Interrogation Centre (JIC) at Humhuma, Srinagar. He was not brought before a magistrate within 24 hours as required by law. Finally, a second PSA detention order (DMS/PSA/95/2010) was issued against him on 31 March 2010. The grounds of detention claimed that Sheikh had been released from prison on 28 March (while he was in fact still in detention) but had been rearrested immediately afterwards because he was forcing shopkeepers to close their establishments and inciting the public to support a call for a general strike. A habeas corpus petition (No. 123/10) is currently pending in the J&K High Court challenging Sheikh’s detention under the PSA and seeking compensation for his illegal detention. His is just one of hundreds of such petitions heard by the High Court every year.

BOX 2: METHODOLOGY

This report is based on research conducted by an Amnesty International team during a visit to Srinagar in May 2010 and subsequent analysis of government and legal documents related to over 600 PSA detentions issued between 2003 and 2010. These documents came from a variety of sources including the J&K High Court Bar Association, leading political parties, individual lawyers, former detainees and family members of current detainees.

Documents prepared by state authorities, in particular the “grounds of detention” required for a detention order to be issued under the PSA, form the main source of information for this report. The report analyzes the allegations against detainees but also the omissions and gaps in the government documents. Where possible, in addition to the government documents, the report also refers to habeas corpus petitions filed by detainees or their family members in the High Court of J&K, (hereinafter High Court) and the judgments / orders of the High Court and trial courts.

Documentary evidence has also been supplemented by testimonies of former detainees, family members of current detainees, journalists, lawyers and members of the State Human Rights Commission met by the Amnesty International team in Srinagar. Where requested, the names of some persons have been withheld. Amnesty International also met the Chief Minister of J&K and senior officials of the state administration including the Chief Secretary and the Home Secretary, Inspector General of Police and the Deputy Inspector General of Police – Criminal Investigation Department. Permission to visit Srinagar Central Prison and other prisons where detained persons are held was also sought, but refused by the government. Officials at India’s

Ministry of Home Affairs in New Delhi declined Amnesty International’s request for a meeting.

3 thoughts on “India’s ‘Lawless Law’ that Keeps Dissidents ‘Out of Circulation’”