This guest post by ALIA ALLANA, a despatch for Kafila from Cairo, is the tenth in a series of ground reports from the Arab Spring. Photos by Alia Allana

A week into protesting, the revolution became about preservation lest someone forgets.

Mohammed Mahmoud Street, the sight of intense fighting was officially off-limits for protestors. A concrete wall separated the protestors and police. Atop the wall army soldiers kept guard. The aim was simple: to keep protestors from barging past and facing-off with the authorities, like they had done for the past few days. But sometime in the night, a maverick with a graffiti can had his way and the beige concrete wall now read, “Change is coming soon.”

Things moved quickly and as the wall went up, a new location was born. The protestors had moved to a new spot: the Cabinet in Garden City. This was home to the incumbent government; agitation against the would-be Prime Minister was already under way. But less than 24 hours after the sit-in was called, Garden City too, had its own tale of sorrow and horror, tear gas and death. A thin line of blood stained the concrete ground, it was visible only if you squinted the eye. Cocooning the trail of blood were two white chalk lines. It looked like a crime scene but the police were involved in this crime; the line was drawn by protestors.

A young boy, Ahmed Sayed El Soroor, 19, had died after he has spent the night chanting and clamoring against the new Supreme -Council of Armed Forces or SCAF-appointed government. “A martyr’s blood must never be forgotten,” said Hani.

Later, news travelled across Tahrir Square that Ahmed Sayed El Soroor had not been murdered, that his death had been an “accident”; that his crushed limbs under the weight of a police truck were borne not of police disdain but confusion and fear. The news didn’t assuage the protestors and many paid homage to the scene of brutality and walked the bloodied trail as it ran along the main road until it came to an abrupt end; it was in the centre of the road the young boy stopped struggling for his life. Doctors say his pelvis was crushed under the weight of the truck. This was at 7:30 am on Saturday.

The night before, as the Friday million-man march came to a close, people on Tahrir Square were mortified and angry. A group of five boys in a tent questioned whether SCAF’s despised Generals thought they were fools: they questioned the appointment of a former Mubarak government member, they were bewildered: how could this move appease them? In the tent, the five and many others I spoke with said, they would never support Kamal al-Ganzouri, recently appointed as the caretaker Prime Minister, even if he had attempted to distance himself from Mubarak, even if he had enacted some good reforms during his last stint in government.

Others who were camping on the other end of Tahrir Square echoed similar sentiments. “He [Ganzoury] is just another pawn,” said Ahmed. As night fell, some hatched a plan – a proposed sit-in at the Cabinet – and it spread like wildfire on Twitter and Facebook. The Cabinet is less than a kilometre away from Tahrir Square. It is pristine and polished. The sculptured buildings have golden trimmings that adorn the top of the buildings. In the centre of the street is a dome-shaped building where an army vehicle is parked behind a tall gate that acts as a barrier between the people and the army. The army soldiers talk amongst themselves, as do the people, but neither party talk to each other; they sneer when their eyes meet.

At nightfall the protestors kept warm by yelling upon SCAF to quit. They called upon Ganzoury to not support the illegitimate government that he would soon head and the gathered vowed to keep fighting. Banners were held up and it seemed as though anger towards the SCAF had grown over the past few days. Tantawi’s concessions of early elections did not make a difference and his assurance that the military wanted no power fell upon untrusting ears.

An impassioned argument broke out between two middle-aged men. One called the people gathered on the square, uncouth mobsters out to destroy the calm of the city. He was jeered upon by the gathered crowd. “What will you put in place of the SCAF?” he asked.

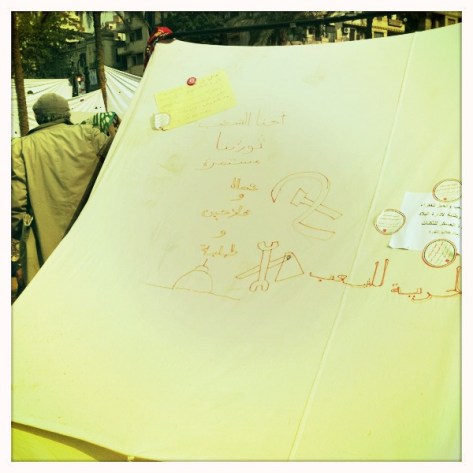

There was not one answer, but many and they were written on walls and painted on the tents.

As the sky darkened and the crowd swelled, the spick and span beige walls against which many leaned, became prey to the thoughts of a few. New symbols have come in the past few days and those calling for Mubarak to leave (Erhal Mubarak) or those of the former president behind bars, are covered by new signs.

The revolution is evolving.

One red symbol on the wall at the Cabinet office is the Anarchy sign and the person with the canister of red spay paint, a teenager with thin stubble has romanticized the idea. “Through chaos we can topple the government,” he says. But chaos breeds further chaos; he doesn’t care about that theory. The challenge of unseating SCAF, the protestors’ central aim, has given birth to more idealistic notions of governance.

On the top of one tent, drawn with a marker is a symbol of the communist party. Inside the tent, plotting about how to bring the downfall of the government are three engineering students. It is nightfall and they are huddled around plastic bags that contain food. Pieces of bread and loose packets of butter has become their staple diet. They get tea from the many tea vendors scattered around the area. They don’t want too much luxury though. “We must remember to keep it simple,” says Matar. Too much corruption, too much robbery has sullied the government, has ruined people’s minds and has reduced the country to groupings of “thugs and thieves,” he says. “Mubarak robbed us with greed,” he says and in the writing of Marx, in the idealism of socialism the three want to fashion a new system of equality.

They hold up a newspaper; it is one of the new newspapers to spring up after the fall of Mubarak. It is flimsy and limp: it contains 4 pages. It is the city’s first self-declared Socialist paper that is produced by the youth. On the walls, the paper is advertised and elsewhere socialist.net has been graffitied. As the sun sets, self-fashion revolutionaries in Che Guevara t-shirts and skinny jeans, sell the paper. Protestors, it seems, are willing to try any system except the one the military will offer.

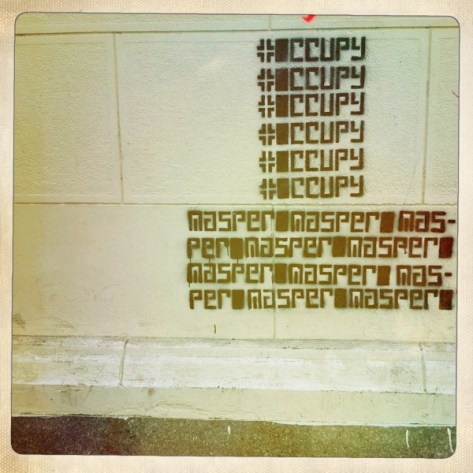

Further along the walls of the Cabinet, a few meters away from the hospital is a brand-new logo. Protestors stop opposite and take pictures, some marvel at the interconnectedness of protest movements across the world. The Occupy Maspero logo resembles the movement that has gripped the US and has now travelled to England. “We are one, brother and sister. We are one damned race,” says a 22-year-old physiology student. Occupy is new trend but it has struck the heart of many and is here to stay, says Nadine.

24-year-old Rami who volunteers at the Cabinet Field Hospital (FH) has taken the Occupy sign literally. Under a muffled voice he informs people about the plan to march to Maspero, to occupy the hated mouthpiece of the government. But Maspero has historical relevance: only last month the army authorized tanks to carpet people under its tires. The horrific image from Tiananmen Square was repeated on the night of the Maspero Massacre, again and again. 29 died. But the people want to take Maspero again and discussion about when to occupy the round building is gaining popularity on Twitter.

In the absence of walkie-talkies, with the lack of a central coordinating committee for the Revolution, people have turned to Twitter, more now than in the January 25 revolution. The impact of Twitter is evident on the wall adjacent to the hotel I stay in, off Tahrir Square. A new haphazard sign dominates the stonewall: #FuckSCAF, it reads. Elsewhere #FuckTantawi. The Twitter graffiti channels anger towards the army generals and the Twitter feed updates furiously.

The youth know whom to hate. As the night was turning into day a new face was going up on the wall under a WANTED sign; that of Hamdi Badin. Great pains have taken to stencil his face, each fold of the skin on his neck, the creases on his forehead and the red beret have been painstakingly drawn. Mobiles come out as the job nears its end; the boy painting the graffiti sneaks a quick last minute look and dashes off before his picture can be taken. Hamdi Badin is the Head of the Military Police and it is the Police who are the real protagonists in Tahrir’s story.

As morning fell, more people came to the Cabinet sit-in. The protestors were chanting for Ganzoury to step down, they wanted him to side with the people and stay on the street. The crowd, riled first by the haphazard appointment of Ganzoury, resorted to throwing Molotov Cocktails at the police. In the medley of Molotov Cocktails and tear gas Ahmed Sayed El Soroor lost his life. The video of his death has been on repeat on the news channels. It plays on the TV at restaurants and coffee shops.

At dinner, in KFC, a family of three discussed the video. They were shaken by his death when they saw the boys eyes roll up. In the coffee shops on Alwy Street, the busiest street of Tahrir Square that maintains normality, the video was conversation amongst a group of middle-aged woman. “How many more will die, when will they realize they can’t win?” Salma asked. She was sitting under a sign that read: The people want the fall of the regime.

Earlier that morning, in a tent in Tahrir Square a 19-year-old boy told me, “We like to die.” He said he left his home three days ago after he kissed his mother; on the forehead to fight. He told her he may not return. He came to fight for a new system and now he has many different ones to choose from – anarchism to socialism yet none of these ideals are represented in the political parties that will contest tomorrow’s election.

Of all the people featured in this story, only one will vote: Nadine.

(Alia Allana is our lady of the Arab Spring.)

Previously in this series:

- Tahrir Square: Egypt, Revolution 2.0

- Tahrir Square: An account of deadly clashes

- Istanbul: Adib Shishakly: The Syrian Rebel in the Hotel Room

- Libya-Tunisia border: Who isn’t a Shabaab these days?

- Jerba, Tunisia: The Synagogue and the Jihadi

- Tunis, Tunisia: “We are not like Iran here”

- Sidi Bou Said, Tunisia: Mickey wants to be the first one to vote

- Damascus, Syria: The Minister for Information maintains that there is no revolution

- Homs, Syria: A day in the rebel stronghold

One thought on “‘Did the generals think we were fools?’ Alia Allana reports from Cairo”