Guest Post by DIVYA BHAGIA

On the face of it, it is hard to believe that our beloved science of economics that has provided enough space to discuss, and at some levels promote, the idea of women’s empowerment could actually be sexist itself. Earlier, I would have offered an aggressive defence of the dscipline. So before I move on, I need to convince you with some facts, just as I had to convince myself that not everything is as it appears and there is enough reason to probe further in this direction.

Leaky Pipeline

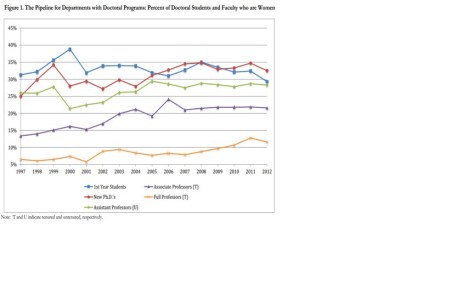

The 2012 Annual Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession reported that there were only 32.5% women amongst all the people who attained a PHD degree in 2012 at 122 economic departments with doctoral programs, and there were only 28.3% women amongst assistant professors, 21.6% amongst associate professors and 11.6% amongst full professors. The fact that an already skewed women-men ratio of 3:7 in the field skews up to 1:9 ratio as we move up does ring the ‘sexist bell’. This pattern which has characterised the participation of women in economics profession for the longest time is referred to as the ‘leaky pipeline’, where we see that women are being dropped out at each step of the academic ladder.

One reason not to dwell deeper on these numbers maybe that the percentage of women as full professors today should depend on the percentage of women as assistant professors say fifteen years back. But as the figure above shows that the numbers for each category remain more or less the same throughout the fifteen years. Also if we look at similar numbers confining ourselves to only top 10 or top 20 Economic departments in the sample, the ‘pipeline’ is even more ‘leakier’.

One reason not to dwell deeper on these numbers maybe that the percentage of women as full professors today should depend on the percentage of women as assistant professors say fifteen years back. But as the figure above shows that the numbers for each category remain more or less the same throughout the fifteen years. Also if we look at similar numbers confining ourselves to only top 10 or top 20 Economic departments in the sample, the ‘pipeline’ is even more ‘leakier’.

Who gets the trophy?

Towards the end of 2014, there was a hue and cry when Economist published a list of 25 most influential economists of 2014 and not a single woman was on it, not even Janet Yellen (the head of the Federal Reserve). But this phenomenon is nothing new, throughout the history we have had very few, in fact negligible women economists who have made it to the mainstream media. Besides that fact, economics is still a field where women do not win prizes. The Nobel Prize in Economics which was launched in 1969 has only had a single women recipient in 2009 and the John Bates Clark Medal that is awarded biennially since 1947 had no woman recipient till 2007.

IMF-World Bank Annual Meeting, October 2012

But do the above facts say enough about sexism in the economics profession? It is easy to disagree and come up with alternative hypothesis other than the hypothesis of sexism to explain the above facts. I will present here some alternative hypothesis and later try to give a valid reason to reject them. One hypothesis is that only 32.5% new PHDs in economics were women, could be because less number of women are interested in the field in general. Even if we were to believe this, it still does not explain why women drop out or are being dropped out at higher rungs of the academic ladder. If not sexism, then it is either because men are biologically smarter at economics than women and are more productive or perhaps because women choose to stay at less demanding jobs as they have a higher opportunity cost of maintaining family life. Also it is easy to argue that ‘leaky pipeline’ and no ‘influential women economists’ are not two separate stories but the latter is a consequence of the former. There is also another line of thinking that accepts that there is enough sexism in the field of economics but the field is just replicating a universal pattern that runs across all professions.

A recently published study by Donna Ginther, Shulamit Kahn, Stephen Ceci and Wendy Williams provides enough quantitative evidence to refute the above arguments. The authors compare academic productivity to outcomes and examine whether gender makes a difference. They find that after controlling for productivity there is a level playing field in most academic fields but economics is not one of them. Economics is an outlier, with a persistent sex gap in promotion that cannot be readily explained by productivity differences (Ginther et al, 2014). So we can at least be sure that there is nothing biological superior about men to explain the differences and nor is economics replicating a universal pattern as it fares much worse than other fields. So then it might be that women drop out at higher rungs to maintain a family life, but then a phenomenon like this which applies to women in academics in general should not hold for any one particular field but be common across all fields unless you believe that economics is the most rigorous. Ginther and Kahn found that a gap of about 16 percentage points persists in the likelihood of promotion to full professor in economics – a much larger gap than in other disciplines (Romero, J. 2013).

But there still remains a fact that we cannot deny that fewer women are taking up economics than men. The difference could come from the conventional view that has parents and teachers guiding girls away from math-heavy classes believing the myth that girls aren’t as good at maths as boys. You might want to challenge my use of the word ‘myth’ if you are Lawrence Summers, but there is enough evidence now doing the rounds to prove him wrong. It is also possible that maybe there are fewer role models to look up to and so lower take-up rates, which in turn leads back to fewer role models and lower take-up rates, forming a self-sustaining cycle. But could there be something else apart from that? Is there something that is specific to economics that only appeals to men? Or is there something specific to the way it is taught that it interests only men? Do we need to change something more than the ‘he’ to a ‘she’ in the textbooks?

References –

- Kimball, M. (2015) How big is the sexism problem in economics? : Quartz India

- Smith, N. (2014) Economics is a Dismal Science for women : BloombergView

- 2012 Annual Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession

- Stephen J. Ceci, Donna K. Ginther, Shulamit Kahn, and Wendy M. Williams (2014) Women in Academic Science: A Changing Landscape : Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Vol. 15(3) 75–141

- Romero, J. (2013) Where are the women? : Econ Focus, Second Quarter

Divya Bhagia is a student at Delhi School of Economics

When Harry Forgot Sally

January 5, 2015 at 8:44am

Ever wondered, how even after decades of ‘scientific’ study of economics and ‘scientific’ application of development policy, gender equity remains a fairytale? Contrary to the aspirations of modern economic science, development policies, both through international and domestic agencies, have only led to a feminisation of poverty as proportionately more women tend to fall below the poverty line. This may have something to do with patriarchal mindsets within the discipline of economics itself.

Only1 woman has won the Nobel Prize in Economics, the rest 74 are all men and only3 women have won the Clark Bates Medal, the other 65 are men. The first woman winner for the latter prize was in 2007, and for the former it was 2009. Mark Blaug’s popular compendium of leading economists in the 20th Century, Who’s Who in Economics, featured only 31 women and a 1000 men. Of the top 100 contemporary economists registered on IDEAS-RePEc global database, women are a significant minority. The works of economist cum historians such as McClowsky and Dimand, have shown that not only are women’s contribution to economics underplayed by men, they are not even given space in footnotes.

Consider for example, the work of unorthodox economist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Herbook Women and Economics, published as early as 1898, was a formidable first, to raise both pressing questions of gender inequality and attempts a framework with which to answer them. A radical activist, who was at that time fighting for universal suffrage, raised analytically the issues of marriage,child-birth, wage gap and education. More importantly, her entire framework was founded upon Darwin’s theory of natural selection and evolution. At the same time, however, the sociologist Thornstien Veblen engaged in debate with her, and pioneered similar ideas. Her ground-breaking contributions were picked up Veblen, only to be forgotten by his followers. Veblen, is today known as the father of evolutionary economics; Gilman, however, is long forgotten.

John Stuart Mill’s Principles of Political Economy, On Liberty has influenced a generation of economists and politicians. He does admit, elsewhere, that his work was inspired by the works of Harriet Taylor Mill, his wife. She who published little in her own name, always contributed significantly to Mill’s work. Mill himself claimed her to be the joint author of his work, and yet, there is a difference between admitting so privately and asserting this fact publicly. Although Mill contributed to the feminist cause and held his wife in highest intellectual regard, the institutional memory of economics was quick to forget this.

Veblen and Mill never got a Nobel for their work, but they would have, if it had been instituted at that time. It took another famous American economist, Gary S Becker, to complete this tragedy. As the leader of the New Home Economics research programme, in the 1960s, Becker found himself relying on the previous works of three economists: Elizabeth Hoyt, Hazel Kyrk, and Margaret Reid. This body of work, 50 years old, suddenly found new life and although New Home Economics was later marred by sexist and offensive conclusions of its male leaders; Becker won the Nobel in 1972. It takes a man to breathe life into the work of women, on issues of crucial importance to women.

Even more depressing is the case of Joan Robinson whose work is acknowledged, grudgingly by even the most ardent critics. Even the Library of Economics and Liberty, says she was “arguably the only woman born before 1930 who can be considered a great economist”. She was a student of Keynes, colleague of Kalecki and Sraffa, and professor to Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz and our very own ex-prime minister, Manmohan Singh! If regular women are given the beti-behen-mata identity, then Robinson was accorded a special student-colleague-professor identity. And so she was never considered an authority, in her own right, and was consequently never given the Nobel. Not only that, she was given full professorship only after 28 years of teaching.

Some might say. Oh this is Western Culture, India never underplays the contributions of her women. Yet how many students know about Krishna Bhardwaj, who founded the famous Centre for Economic Studies and Planning (CESP) at JNU? Indian public has appreciated Jagdish Bhagwati, Amartya Sen and Prabhat Patnaik, but have they appreciated the works of stalwarts like Devaki Jain, Utsa Patnaik (ironically Prabhat’s wife); or of Bina Aggarwal, Jayati Ghosh, Sudha Narayan or Reetika Khera who are doing cutting edge work today?

Others can say that this is not merely limited to the economic sciences, but equally applies to other sciences as well. One of the more important yet subtle messages of the TV series Cosmos: A Space-Time Odyssey was that the contributions of women have been underplayed even in the natural sciences. Take for instance the case of geologist, Marie Tharp who discovered the Atlantic rift valley, that verified Continental Drift theory. Her name is not even mentioned on the “ContinentalDrift” Wikipedia page. Henrietta Leavitt told us how we could use luminosity to gauge inter-galactic distances, while Cecilia Payne let us find the temperature of stars by looking at their spectrum. Their names have been lost in the mainstream. And, no, the fact that Marie Curie got two Nobels, does not balance the suppression of many other women scientists.

However,it would be safe to say, that a male understanding of the social world is worse than a male understanding of the physical world. The promises of classical liberalism- political and economic freedom, will be continue to be denied, if social science remains gender blind. So, more than natural science, it is social science that needs to introspect.

Male gatekeepers to journal publications, academic posts and to the flow of ideas concerning issues of gender; have successfully negated the energies of women scholarship. The issues remain; a significant gender gap in wages, employment,economic security and mobility. If the structure of gender, either in the workspace or in the family, is to be tackled by economic theory, we must recognise the contributions of women economists and demand that the discipline no longer keep such issues outside its core research agenda. When faced with issues of gender, if graduate students cannot come up with a better response than the old mantra of “privatisation,liberalisation,globalisation”, then economics is more conservative apology than emancipatory science.

Pranjal is an undergraduate student of economics at Presidency University, Kolkata.Comments and suggestions can be sent to rawat.pranjal007@gmail.com.

LikeLike

Regarding the claim that economics may be an outlier among scientific disciplines, we have recently published some hiring data that examined hiring preferences in four disciplines–economics, engineering, biology, and psychology. In all fields there is a preference for hiring entry-level (assistant professors) who are women and this is true for both male and female faculty. The only exception is male economists. They do not appear to have a statistical preference for hiring either gender. Our article is available at: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/04/08/1418878112.abstract

LikeLike

I draw Divya’s and Pranjal’s attention to:

Kirsten K. Madden, Janet A. Seiz and Michèle Pujol [2004], A Bibliography of Female Economic Thought to 1940, London and New York: Routledge.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. V. Useful

LikeLike