[Below is the English Version of a Public Statement in Malayalam released by a group of concerned economists and social activists that appeared in the Malayalam and Kerala-based English Newspapers today (31 October 2025)]

Background: The Government of Kerala have been preparing to declare the State of Kerala as India’s First Extreme Poverty-Free State on 1 November, 2025 being the State formation day. Th government claims that this achievement was attained through sustained efforts to eradicate extreme poverty in the state since July 2021, with just 64,006 extremely-poor families identified through a survey conducted by the Kudumbashree Mission and the Panchayats and Municipalities. The criteria used, as the government claims, were (i) households with no income, (ii) not even food for two times a day, (ii) those unable to cook food even with food articles available from ration shops, and (iv) those with very bad health conditions. This makes Kerala the first state in India to attain the two Sustainable Development Goals of No Poverty and No Hunger. However, this raises a number of crucial questions. It is in this background the following public statement was issued.

Thiruvananthapuram

30 October 2025.

Is Kerala a Destitute-free State or Extreme Poverty-free State?

1. What were the criteria used to identify the ‘extreme-poor’ (athi dharidhrar in Malayalam) in the state? Which reliable committee carried out the survey? The government must make public the study report and establish the credibility of the data used to back up this declaration.

2. The public distribution system in Kerala has recognized four different groups, in consonance with the National Food Security Act of 2013. The bottom group in Kerala have been included in the Antyodaya Anna Yojana who have been given yellow colour ration cards. According to the state government’s Economic Review 2014, these card holders bracketed as ‘Most Poor’ total 5.92 lakh households. The state government has been supplying them with free rice and wheat since 2023. The central government has been making rice available at 3 rupees per kilo, and wheat, at 2 rupees per kilo. So how can the government claim that there are only 64,004 extremely-poor households in Kerala? Or are they claiming that the 5.92 lakh yellow-card-holders have climbed out of poverty and so it is possible to declare Kerala extreme-poverty-free? In that case, is AAY not relevant to Kerala anymore? What will happen if the central government stops its support to AAY in Kerala once the state is declared as Extreme-Poor Free’?

3. According to a note released by the Kerala government’s Department of Local Self-Government, the ‘extremely-poor’ are those who have no income at all, those who lack two meals a day, those who have no means to cook even if they receive rice rations, and those whose health is very poor. In that case, shouldn’t these households belong to the category of ‘destitutes’ (agathikal in Malayalam)? Is it this group that the state government is now labelling as ‘extremely-poor’?

4. Is it not a fact that in 2002, the then-Kerala government started a project called Ashraya which was tasked with identifying destitutes and offering them support? This project had won the Prime Minister’s award in 2007. How many families were originally identified as destitute back then? Where does that number stand now? That project was later converted into one that targeted extreme poverty. Is the current one a revised version of the older Ashraya? The Ashraya as well as the projects that followed it were put together by integrating such programmes as the Indira Awas Yojana. Is the present push for this extreme-poverty-free state a continuation of this? Is it not a puzzle that the original list which had 1, 18,309 households has now shrunk to 64,0006?

5. What is the empirical basis for the claim that these households have overcome extreme poverty? Have these families received any benefits from central government programmes?

6. According to the 2011 Census, there were 1.16 lakh households belong to the Scheduled Tribe group (locally known as adivasis) in Kerala, and the total adivasi population was 4.85 lakhs. But in the new numbers, just 6400 of these families have been identified as extremely poor. That is, a mere 5.5 per cent. Are they of the destitute category? Or do they belong to the extremely-poor AAY beneficiaries? What magic has let them overcome extreme-poverty now?

7. Is the survey report that reveals the actual conditions of life of other sections who suffer from extreme poverty available?

8. What was the actual methodology adopted for the survey? Was it limited to receiving lists of recommendations from local self-governments?

9. Are not the scheme workers, including the ASHA workers (now on an unbroken 266th day of protest in front of the Government Secretariat), who receive a mere Rs 233 per day, and similar informal workers, still suffering from extreme poverty?

10. Had there been any discussion with the state’s Statistical Department or the Kerala State Planning Board, about the criteria used in the survey? Poverty is the most insidious socio-economic challenge that our country faces. Eradication of extreme poverty is not to be taken lightly. Making it a propaganda item is indeed unacceptable. Therefore, we humbly request the government to kindly respond to the above questions and doubts with answers based on credible data and facts.

- Professor RVG Menon (Social and People’s Science activist and Former President, Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad).

- Professor MA Oommen (Honorary Fellow, Centre for Development Studies and Hon. Distinguished Professor, Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Professor KP Kannan (Honorary Fellow (and Former Director), Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, and Former Member, Erstwhile National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector, Government of India).

- MK Das, (Author and Former Resident Editor, The New Indian Express, Kochi).

- Dr. G. Raveendran (Former Additional Director General, Central Statistical Organisation, Government of India and Honorary Fellow, Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Dr. KG Thara (Former Director, Kerala State Disaster Management Agency).

- Professor V Ramankutty (Former Professor of Public Health and Head, C Achutha Menon Centre for Public Health Studies, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram and Chairman, Health Action by People, Kerala).

- Professor KG Sankara Pilla (Poet, Social Activist and a Pioneer in Modern Malayalam Theatre).

- Professor Sunil Mani (Former Professor and Director, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Dr. MP Mathai (Former Professor of Gandhian Studies, MG University, Kottayam).

- Professor J Devika, Centre for Development Studies, and Althea Women’s Friendship.

- Dr. NK Sasidharan Pillai (Former President, Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad)

- M Geethanandan (Social Activist and Organiser of Adivasis)

- Professor CP Rajendran (Former Professor of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore).

- Professor K Aravindakshan (Former Professor and Collegiate Director, Government of Kerala, Ernakulam).

- Sarita Mohana Bhama (Poet and Former Journalist).

- Professor John Kurien (Former Professor, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Dr. M Vijayakumar (People’s Science Activist and Executive Director, Health Action by People, Kerala).

- R Radhakrishnan (Former President, Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad).

- Joseph C Mathew (IT Specialist and Social Activist)

- Professor KT Rammohan (Former Dean, School of Social Sciences, MG University, Kottayam).

- Sridhar Radhakrishnan (Environmental Activist).

- Professor P Vijayakumar (Former Professor of English, University College, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Dr. Mary George (Former Professor, University College, Thiruvananthapuram).

- Dr. M Kabir (Former Professor of Economics, Government Women’s College, Thiruvananthapuram).

NB:

I do believe that these questions , below, are a necessary beginning, but a fuller critique of the Kerala government’s claim to have eradicated extreme poverty must be made. As a researcher of gender and labour in the state, I can say without hesitation that this declaration rubs salt into our wounds. If Kerala is relatively free of poverty since the 1990s should not be used to mask the fact that resource-poor women, informal sector women workers, have kept on carrying the steadily-rising burdens of social reproduction, including that of governmental labour around welfare distribution at the local body-level. Indeed, the very survey that the government claims to have done as a basis for the recent anti-poverty interventions were conducted in large measure by mobilising lower-middle-class women’s governmental labour through the Kudumbashree, the ASHAs and others (as publicly admitted by the member of the Kerala State Planning Board, K Ravi Raman).

Secondly, it cannot be allowed to deflect attention from the enormous burden of debt that poor families bear, which most often rests on the shoulders of women, and which has been rising at an alarming pace. Micro-credit, and not just government subsidised forms, is the very fuel on which normalcy is maintained in the domestic front here, and it is not as if the government does not know. Unfortunately this celebration — and the craven Malayali media (see for example, S R Praveen’s article in The Hindu, Thiruvananthapuram edition, today) will not ever question it seriously — works to muffle any critical discussion on the mounting, unrequited, unrecognized labour of women in Kerala, and the fact that the government, including the present Left-led regime, is a major exploiter of women’s labour here.

The ASHA workers’ struggle has ripped apart the mask, but the government continues to milk the gullibility — and probably the unconscious fears — of liberals outside Kerala through such stunts as these. This letter asks some serious questions about the credibility of this announcement and the integrity of the government making it, but one must also question, in a more fundamental sense, the politics of a government, leftist or otherwise, which tries to project ‘extreme-poverty’ as anything other than a moving target, especially in times of extreme socio-economic inequalities, rising consumerist aspirations setting the standards of what counts as the good life, and the steady takeover of capital in health and education in the state.

The circulation of this set of questions in the Malayalam public sphere has roused the fury of the members of Pinarayi bhajan sangh, with or without some social science training. Some of it is outright comical. Some of them accuse Prof Kannan and the other senior economists of the desire to travel abroad and win accolades — clearly they have no clue about the stature of these academics in India and abroad, and of their ground-breaking work on poverty and development in Kerala.

One especially-irked Village Extension Officer even says that he would have liked to come over and “slap two times” those who ask such questions — but in his infinite mercy, he chooses to launch into a long account of his sallies into the Kerala countryside as the Poverty-Dragon Slayer, clad in shining governmental armor, endlessly training and deploying — who else — Kudumbashree women, ASHAs, ‘volunteers’ all (not ‘workers’, PV forbid!) to carry out the identification.

Of course, he does not do it mechanically: the identification agents use the latest tech (sexy!), and the methodology, apparently stronger because lakhs and lakhs of people participated in the identification process — is flexible enough to notice that someone owning a 25 cent plot of land in Kerala may be in dire ‘poverty’ as the land can’t be sold because of legal issues. But then the rant does not answer any of our questions — for example, why surveyors so keen to classify the owner of 25 cents in a temporary crisis as ‘extreme poor’ missed so many adivasis and government scheme workers. Perhaps the first part of the above sentence answers the question about the second? Indeed, that is precisely what we intended to do when we asked to see the data. If that actually happened, no wonder Mr VEO has flown off his handle when faced with a polite set of requests for data and clarification. But the gentleman is definitely truthful, for he does not want to make any comment about the “implementation” part!

But most importantly, development is most truthfully delivered by the likes of Mr VEOs because ward members would typically want to add many more families from their wards — cheap politicians, right? No Mallu welfare queens permitted, right? Just some weeks back, an article in the EPW by Binitha Thampi and Varsha Prasad on the ongoing ASHA workers’ protest claimed that it was being supported mainly by a sentimental “middle class” that fell for the women’s weepy stories. Some of us had to respond, reminding them that the concept ‘civil society’ might have been a better fit, and much support has rested on concerns other than the human tendency to feel for a suffering other. For Thampi and Prasad, the latter is something we’d better avoid when thinking about welfare distribution, but it seems to have been THE guiding principle, reading the accounts of the apologists of the Nov 1 declaration, from ex-Chief Secretary Sarada Muralidharan to our Knight, the good VEO, both of which are pretty sentimental and feel-good mush. But now is their golden chance, to actually discover the ‘middle class’ : Thampi and Prasad should read his note. Mr VEO’s note is perfect in its display of middle-class self-satisfied condescension, the middle-class saviour complex in full blast, and full-on sentimentalism (triggered by a narrative of his rescue of an extremely-poor family).

It is not surprising perhaps to note that such an innocuous and humble set of questions to the government — surely the right to ask questions is part of citizenship in India still– should elicit such intolerance and rage. But then, that seems to be the flavour of this seemingly-unending season. From the VEO’s account, democracy seems to be about benevolent neoliberals delivering targeted welfare using unrecognized, poorly- or unpaid female labour, keeping things flexible enough to accommodate whoever some groups identify as distressed. If anyone questions this, that can solely because the questioner has an ulterior motive and is ultimately ungrateful to the benevolent state (PV, in this case, our visible God and all of the state too) that is like a Father in its concern for the poor.

With all respect to the former LSG Secretary Sarada Muralidharan, her FB note that lays down the details of the identification exercise gives no comfort. Ms Muralidharan seems to admit that there was no formal survey and the ‘greatness’ of the exercise stems from the mass participation of some 13 lakh people. That may be excellent in a crisis triggered, for example, by a disaster, but the reliability of data is not improved by mass participation. Ms Muralidharan may wax eloquent on the breathtaking levels of participation, but sadly, we are seeing how many have been left out! Clearly, the ‘local’ is not La La Land or Mavelinaadu, for that matter, however we may wish that.

Remember, all the institutions that Mr VEO and Dr Ravi Raman mention as participants in the survey are stuffed to breaking point with PV bhakths — the KILA, Life Mission, Kudumbashree (after the secret ballot in Kudumbashree elections, the CDS leadership in a great many LSGs are of women keen to do PV’s bidding), the bulk of scheme workers, including the ASHAs are desperately dependent, not just economically but also socially, on the CPM, CITU, and so on. Bias in welfare distribution is well-documented in the research literature on Kerala’s history of welfarism — so as social scientists, some of us simply wanted to know! No one really reminded them of the elephant in the room, CPM nepotism and the huge bias it entails, but that doesn’t matter because even the slightest seed of doubt must be violently eradicated first, irrespective of whether poverty has been eradicated or not.

Therefore, asking questions, however politely, is blasphemy in present-day Kerala, and asking them publicly? Shantham paapam, is all I can say! I can imagine Mr VEO gritting his teeth in the intense though still-hard to realize desire to knock me down and kick my face. If only we had a CPM version of …

Adding to the fun is new evidence:

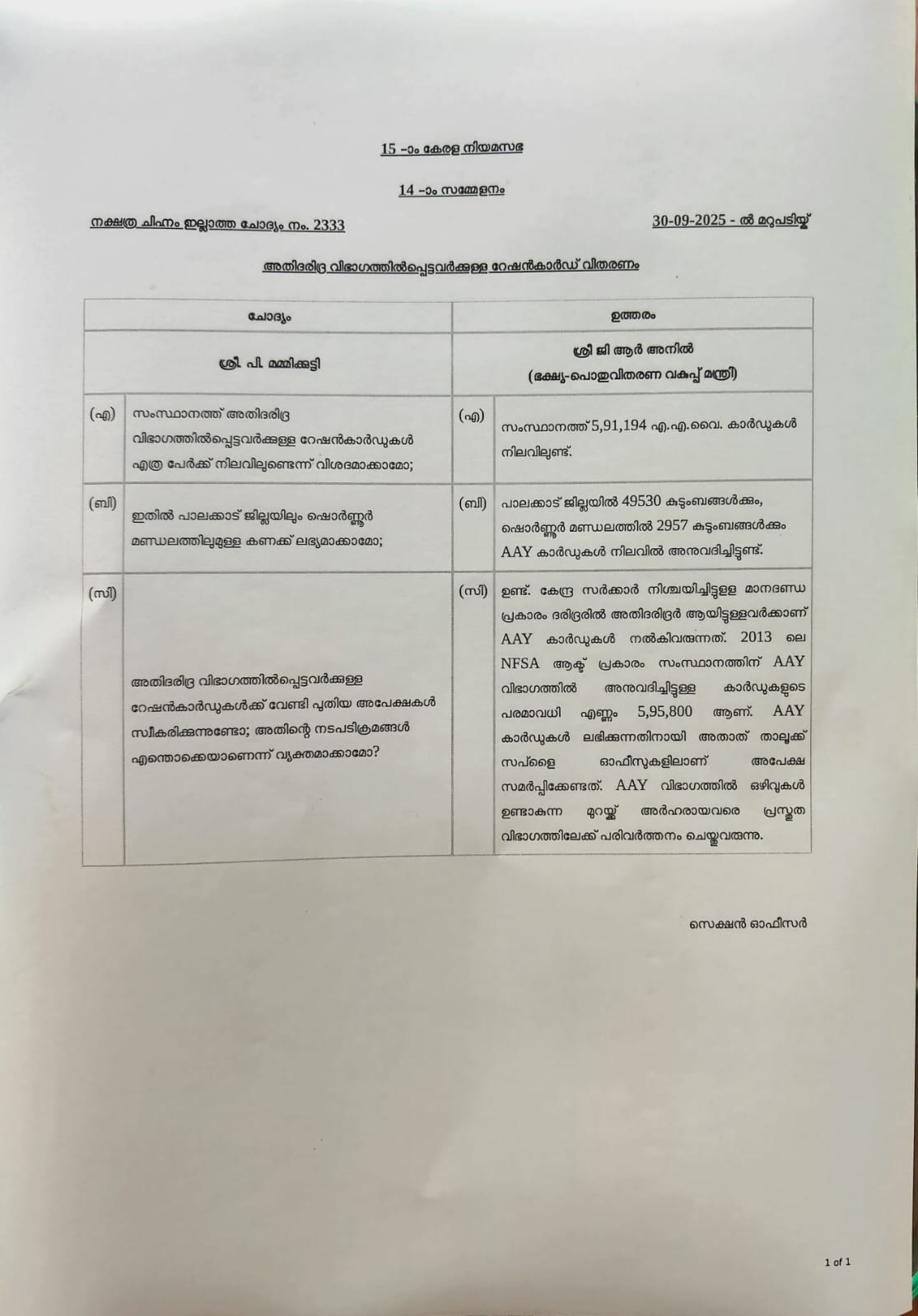

This is the response received by the Shoranur MLA Mammikutti to his unstarred question no 2333, at the 14th session of the fifteenth Kerala Legislative Assembly, around a month back, on 30 Sept. 2025. It says that there are 5, 91, 194 AAY cards in Kerala!

This is the reason why we, as responsible social scientists, want to know all about this new tech-sexy, ‘flexible’ methodology — it appears magically neoliberal in its ability to reduce the numbers of the poor.

2 thoughts on “Is Kerala a Destitute-free State or Extreme Poverty-free State?”