Nation-states have a logic of their own. So insidiously is this logic purveyed through the state’s institutions that it becomes common-sense, particularly among the educated. Perspectives that differ from this common-sense are then easily seen as signs of illiteracy, or more dangerously, treachery.

A woman employed for housework by a Pakistani living for a while in Delhi, could never quite understand where her employer was from. “Bahar se?” she would ask, “Amreeka se?” No, would come the patient reply: from outside, yes, but not from America, from Pakistan. Where is that? ‘Well, you know that “here”, yahan is Bharat? India? Hindustan? I am from vahan, there, Pakistan, another country’. But yet again, the domestic help’s bewildered response – yahan matlab Dilli? Here, meaning Delhi?

She seemed to have escaped even the common-sense that demonizes Pakistan. Had she gone to school, had she been a migrant from another part of the country, she would have had some notion of India-that-is-Bharat. But that is precisely the point – the recognition of the Nation, the feeling of belonging to it, must be learnt. It must, as Benedict Anderson famously put it, be ‘imagined’. Which is not to say that the Nation is imaginary, in the sense of unreal, but rather, that it has to be imagined, conjured up, called into being by a vast political project operating at many levels – the Nation is not simply that land-mass lying in the ocean, an easily recognizable object.

This imagining excludes as many groups as it includes, and when they in turn, fail to recognize the nation, it is they who are the traitors. I remember overhearing a snatch of horrified conversation between students of Delhi University – “You know, Naga students say they’re going to ‘India’ for ‘Delhi’ whenever they leave Nagaland…” The horror is – we consider Nagaland to be part of India, but they don’t consider themselves to be part of us. How generous and inclusive our nationalism, how separatist and exclusionary theirs. Consider the conflation here between Us and India, and the division between the territory and the people. The territory that is Nagaland is an ‘integral part’ of India, but the Naga people can be Indians only under stringent conditions – not on their terms, but on ours. Nagaland is ours, but not the Naga people, not if they insist on being Naga.

I learnt from a friend working on text-book revision in Leh, that for decades school-children of Leh have read text-books using images that make no sense to them – flora and fauna not local to the region, for example. But what I found most striking was that generations of Ladakhis have read the same text-books used all over the country, that say – “The Himalayas lie to the North of us.” Really? Not if you are in Ladakh. Check out a basic tourist guide. How could any Ladakhi have felt part of that “us”?

So, should we work towards a more inclusive nationalism? But to whom does that pronoun ‘we’ refer? Can Ladakhis or Nagas ever say, referring to the rest of India – ‘we’ should include ‘them’? That proud ‘we’ can only be occupied by dominant, mainstream groups within the nation. Hence – We won the Test match. We have the bomb. But never – Weare about to be drowned, any day now, by the Indira Sagar dam on the Narmada. The first ‘we’ is eleven men, the second ‘we’ a tiny state elite, the third ‘not-we’, thousands of inhabitants of twenty-five villages in Harsud. But no, numbers don’t count.

The point then, is not about inclusion. The point is to question the very legitimacy of the nation-state as the arbiter of inclusion, of identity. To question the barbed-wire borders, the ethnic cleansing, the National Interest, the ‘illegal’ immigrants – why shouldn’t people simply move to wherever there is work? After all, there are no barbed wires for capital, not any more. At Wagah, on the border between India and Pakistan, at sundown you can witness the sad spectacle of nation-states producing identity. The “Beating the Retreat” ceremony enacted daily is a dramatized performance of hostility. The drill is a series of choreographed moves of aggression, and this performance is wildly applauded by the audience on both sides, with shouts of Pakistan Murdabad or otherwise, as appropriate. (One evening at Wagah would certainly sort out the domestic worker I referred to earlier. An effective crash course on what Yahan means).

Once upon a time, when nation-states emerged, in the 19th century in Europe and in the 20th in Asia and Africa, they bore the electric charge of opposition to empires. Once settled in however, each nation proceeded to obliterate rival nations within, both potential and actual. The process of creating the French citizen, the historian Eugen Weber tells us, was no less violent than colonialism. Nation-states can only be authoritarian, non-inclusive, geared to the interests of a tiny elite.

This is the framework within which I want to post here a chapter, “When was the nation?” from the book Aditya Nigam and I wrote, Power and Contestation. India after 1989 (published in 2007 by Zed Books, London and in 2008 by Orient Longman, Hyderabad.) Completed in 2006, it is necessarily dated, and I have not attempted to bring it up to today, because the point here is only to make the argument.

I do this in the somewhat forlorn hope that conversations and disagreements can carry on without becoming utterly polarized into two assumed camps; in the hope that other ways of thinking about building democratic communities can be imagined than nation-states with their strictly policed barbed wire borders; in the hope that a simultaneous critique of “India” and of other equally “homelandist” imaginations, in Sanjib Baruah’s words, is possible…

Kamla Bhasin has a beautifully appropriate line of poetry that captures this forlorn but stubborn hope:

Main sarhad pe khadi diwaar nahin

Us deewar pe padi daraar hoon.

I am not the wall that seals in the border

I am the fissure breaching that wall.

When Was the Nation?

It should have become evident by this point in the story, that the ‘idea of India’[1] has been a deeply contested one from the moment of its emergence in the nineteenth century. This perspective will emerge more starkly as we discuss some of the most outstanding political conflicts in India today, in the early twenty-first century. Sudipta Kaviraj has pointed out how ‘European models of nation formation’, in which cultural unification preceded the coming into being of the nation-state, were understood by Indian nationalist leadership of all shades to be paradigmatic and universal.[2] Consequently, the nationalist myth, whether secular-Nehruvian or Hindutvavaadi, involved the idea of an already existing Indian nation formed over thousands of years, waiting to be emancipated from British rule. In this understanding the Indian nation had been for millennia ‘an accomplished and irreversible fact’ and any voices that questioned this were of necessity ‘anti-national’. (Kaviraj 1994: 330).

However, there are regions and peoples residing in the territory that came to be called called ‘India’, which have histories autonomous of the Indian nation-state, and which had independently negotiated relationships with the British colonial government. One of the significant achievements of the nation-building elite of what subsequently became India, was the incorporation into the Indian nation of these peoples and regions, at varying degrees of willingness. The hegemonic drive of the anti-imperialist struggle as well as the coercive power of the Indian state after independence was deployed to enforce the idea of India as a homogeneous nation with a shared culture. Its very diversity was supposedly its strength, the popular nationalist motto being ‘Unity in Diversity’. However, the idea that all the multiple identities and aspirations in the landmass called India are ultimately merely rivulets flowing into the mainstream of the Indian nation, was never an unchallenged one. The project of nation-building therefore, sixty years down the line, continues to be a fraught exercise.

In this chapter we will discuss two striking illustrations of this argument – the north-eastern region of India and the state of Kashmir in the north. However, it would be misleading to assume that these two well-known ‘trouble spots’ on the borders of India are unique instances of the crisis of the nation-state. Before we move on to Kashmir and the North East then, let us consider some other instances that illustrate the perpetual anxiety generated by the need to preserve a nation – assumed to be simultaneously eternal and perpetually under threat of disintegration.

First, the issue of linguistic reorganization of states, a long-standing commitment of the Congress leadership prior to independence. It was recognized that the British government’s rationale for forming provinces was purely that of a colonial power. The Motilal Nehru Committee report (1928) therefore held that the ‘linguistic unity of the area’ should govern redistribution of provinces. After independence however, the Linguistic Provinces Commission, set up in 1947, rejected the idea, warning that the assertion of linguistic identities could jeopardize the unity of the Indian nation (Arora 1956). The nationalist leadership as a whole was opposed to such states, Krishna Menon for example, warning that ‘We will Balkanise India if we further dismember the State instead of creating larger units’ (Noorani 2002). However, the popular mood forced a rethinking. The movement for Telugu-speaking Andhra Pradesh which began with Gandhian fasts in 1951 turned to mass violence in 1952, and the state of Andhra Pradesh was formed in 1953. Other movements for language-based states developed, mobilizing all the passion and emotiveness associated with nationalist sentiments (REFS). The fear of the nationalist leadership at the centre, that linguistic provinces would have a ‘sub-national bias’ that could strain a nation ‘still in its infancy’ (Navlakha 1996: 81) was apparently well-founded. Nevertheless the mass base these sentiments drew had the backing of regional leaders, and finally the States Reorganization Act of 1956 created language-based states. Since then there have been other new states created under pressure from mass movements, the latest being Uttaranchal (from UP), Chhattisgarh (from MP) and Jharkhand (from Bihar) in 2000.

Innumerable and continuing disputes over water-sharing between states, which go beyond bickering between state governments and often take a popular form, are another indicator that the idea of India cannot be assumed but must be subject to a ‘daily plebiscite’ (Renan 1996: 53). One instance of this is the Cauvery water dispute between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, resulting in rioting and violence against Tamilians in Karnataka (1991), and the Karnataka government refusing to abide by the Supreme Court directive in 2002 to release water to Tamil Nadu (Menon 2002). Another dispute, on-going at the end of 2006, is between Kerala and Tamil Nadu over the Mullaperiyar dam on the Periyar river arising from an agreement between the British government of Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu) and the Princely State of Travancore[3] (now part of Kerala). Significantly, the opposition of the Kerala government to Tamil Nadu’s rights to Periyar waters is sometimes expressed in the language of independent nation-states – that the colonial government had arm-twisted Travancore into an agreement that was disadvantageous to it, and that Kerala today should consider its own interests first (Special Correspondent 2006 a : 1)

The state of Tamil Nadu and its politics offers another fascinating example of the complex relationship to India that most of its constituents have. The anti-Brahmin Dravidian movement that is the overwhelming political force in the state, was flamboyantly secessionist up to the 1960s, when the threat of being banned under Nehru’s legislation of 1963 made many of the parties modulate their demand. Over the decades however, the politics of the state has continued to assert Tamil cultural nationalism and to organize militantly against the imposition of Hindi. The politics of a pan-Tamil identity plays out in continuing links with Sri Lanka’s Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). In 2002, the General Secretary of the party Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK), Vaiko, was arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act for a speech the Tamil Nadu government held to be ‘calculated…to stimulate secessionist sentiments in Tamils and to enhance the LTTE’s support base in Tamil Nadu’ (Venkatesan 2004).[4] It is reported that secessionist Tamil nationalist groups with links to LTTE are ‘mushrooming’ in Tamil Nadu, with the aim of an independent Tamil homeland including the Tamil-speaking parts of the southern states of India as well as of Sri Lanka (Iype 2000). Paradoxically, at the same time, Tamil Nadu in many ways by the 1990s seems to have entered the national mainstream. As we saw in the first chapter, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) are now decisive at the centre in the era of coalition governments, and as parties representing OBCs in a post-Mandal age, see themselves as participating in a nation-wide community of assertive backward castes.[5]

Thus, there are several simultaneous levels at which ‘non’, ‘sub’ and ‘cross’ national identities manifest themselves. However, the two most dramatic flash-points continually interrogating the nation continue to be the North-East and Kashmir.

The ‘North East’

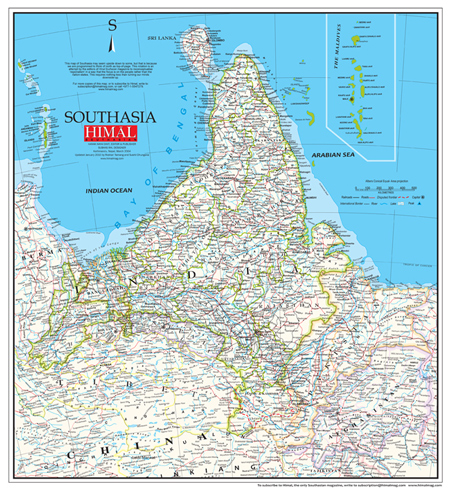

The term ‘North East’ refers, in independent India, to the eastern Himalaya and Brahmaputra valley of the India-Myanmar border, comprising the seven states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura, these ethnicity-based states being formed at various points between 1963 and 1987.

There is increasingly a sense among scholars of this region that the term ‘North-East’, is an ‘illusive construct’ (Misra 2000:1) and falsely homogenizes ‘a bustling terrain sprouting, proclaiming, underscoring a million heterogeneities’ (Hazarika 2000: 34). The term is unavoidable at one level – this roughly triangular piece of land is linked to the rest of India only by a narrow corridor 20 kilometres wide at its slimmest point, referred to as the Chicken’s Neck. Other commonalities are also acknowledged, such as that several of these states were once part of the state of the undivided state of Assam, and that they share problems such as communication bottlenecks, drug-trafficking, illegal immigration and insurgency. Nevertheless, it is misleading to assume a common North-East perspective, because the states have distinct histories and cultural traditions, different relationships with the British colonial government as well as different levels of interaction with mainland India.

More importantly, we recognize the implication of recent scholarly work that the region cannot be understood solely as the ‘north-east’ of India. It is after all, also the ‘north-west’ of South East Asia. Ninety-eight percent of the borders of North-East India are international borders. This region is part of a tropical rainforest that stretches from the foothills of the Himalayas to the tip of the Malaysian Peninsula and the mouth of the Mekong river, spanning seven nation-states. In terms of peoples, it is marked by ethnic affinities that cut across national borders and movements of populations across the region irrespective of nation-states, dictated by traditional forms of livelihood and ecological factors. Like other such border regions, this one too, exemplifies the tensions produced by the idea of bounded nation-states. From the viewpoint of nation-states, cross-border affinities can only be ‘anti-national’ and unregulated movement across borders can only be ‘illegal immigration’. As Walter Fernandes puts it, ‘the North-East’ could be understood as a gateway to closer ties with South-East Asia and China, but the Indian state ‘seems to be obsessed with security and treats this diversity as a threat and the region only as a buffer zone against China’ (Fernandes 2004: 4610).

At the same time, the logic of the nation-state is overwhelming. In a context of extreme economic and cultural alienation of indigenous or local populations, the ‘foreigner’ issue is also on top of the agenda of many ethnic movements in the North-East. In 1983 nearly two thousand immigrant Bengali Muslims were massacred in Nellie (Assam) by Tiwa tribals, both killers and killed being extremely poor and desperate people. The issues raised by the Nellie massacre remain unresolved until today, with roots going back a very long way – starting with colonial conquest; the establishment of individual rights to private property; the consequent dispossession of indigenous people whose control over resources had been governed by the rules of pre-capitalist social formations; large-scale immigration from the rest of the country and from neighbouring countries, especially Bangladesh; and the continuation of a colonial attitude towards the North-East by the Indian nation-state (Hazarika 2000:25-48; Baruah 1999:ix-xx).

Insurgency and state repression

The most significant axis of conflict in the region for decades has been that between the Indian state and political movements demanding differing degrees of autonomy including complete independence. The creation of different ethnicity-based states over the years could be said to have met some of the regional aspirations, but this could not compensate for deep imbalances in economic development and the centralised exploitation of natural resources for a national-level elite. The Assamese elite for instance has always resented the meagre returns from the Centre for its oil and gas reserves (Assam contributes about a quarter of the country’s total oil production), both in terms of revenue and development of ancillary industries, which are largely located outside the state (Hazarika 1995). The emerging middle class elite of Assam thus led a movement that addressed economic issues but which embraced also the whole question of identity, culture and language.

But most movements here are armed struggles for independence from India, which is regarded as an occupying power that moved in after the British left. For example, in 1947 the kingdom of Manipur had been constituted as an independent constitutional monarchy with a democratically elected Assembly, but the king was arrested under instructions from the Indian government and the state forced into a merger with India in 1949. Similarly, the Naga National Council (NNC) as early as 1929 had met the Simon Commission (set up to examine the feasibility of self-government for India), to petition against Indian rule over Nagas once the British pulled out. When a Naga delegation met Mahatma Gandhi in 1947, he supported the Naga right to independence. He said – ‘I believe you all belong to one, to India. But if you say that you won’t, no one can force you…I will go to Naga Hills and say that you will shoot me before you shoot a single Naga’ (Baruah 2005a). By that time, Gandhi’s distrust of the emerging nation-state was already irrelevant to mainstream politics. Under the Hydari Agreement signed between NNC and British administration, Nagaland was granted protected status for ten years, after which the Nagas would decide whether they should stay in the Indian Union or not. However, shortly after the British withdrew, independent India proclaimed the Naga Territory to be part of the new Republic.

Thus, it is important to note that insurgent groups such as ULFA of Assam and NSCN-IM of Nagaland [6] insist that they are not ‘secessionist’ movements, asserting rather, that Assam and Nagaland were never part of India. Both of these consider themselves to be independence struggles for self-determination against the occupying army of a colonial force.[7]

One of the crucial measures that enables the Indian state to keep under control the incendiary situation in the North-East is the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), passed in 1958. Under this legislation, all security forces are given unrestricted power to carry out their operations, once an area is declared ‘disturbed’. The AFSPA gives the armed forces wide powers to shoot, arrest and search. It was first applied to the states of Assam and Manipur and amended in 1972 to extend to all the states in the region, continuing in force until today. The enforcement of the AFSPA during almost five decades in Assam and Manipur and over three in the rest of the region, has resulted in the widespread practice of arbitrary detention, torture, rape, and looting by security personnel. In effect the entire population of the North-East is viewed as ‘the enemy’ in a civil war. This legislation is justified by the Government of India on the grounds that the region is an integral part of the Indian Union, which cannot be permitted to secede. The AFSPA is ‘an act of legitimizing the involvement of the military in the domestic space’, and ironically, represents the Indian ‘9/11’ – it was passed on the 11th of September 1958 (Akoijam and Tarunkumar 2005: 7).

We will now take a quick look at three of the states in the region, to indicate the complexity of their histories and their relationship to the Indian nation.

Nagaland The oldest armed ethnic movement in India is the Naga struggle, which for almost six decades now, has been confronting the might of the Indian state with its demand for a sovereign Nagaland. The Naga National Council announced a ‘Declaration of Independence’ in 1951 and successfully boycotted the 1952 elections. Armed struggle has continued since then. In 1975 by the Shillong Accord, the Naga leadership agreed to renounce violence and work within the Indian constitution. This was perceived as a betrayal by many, and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland was formed in 1980 to carry on the struggle for independence, splitting in 1988 into two factions. The Isaac-Muivah faction (NSCN-IM) is now the chief militant organization of the Nagas, still has vast influence in Nagaland and Manipur and is capable of inflicting heavy losses on Indian security forces. It virtually runs a parallel government in some of the remote areas despite the fact that like many other insurgent organizations, it was banned almost since its formation, and functioned ‘underground’, the ban being lifted only in 2002.

The question of the self-determination of Nagas is a complex one despite a general agreement that there is a ‘Naga way of life’ that is distinct from that of the Indian mainstream. The Nagas are a conglomerate of close to forty sub-tribes, and the two factions of the NSCN (the other faction being the NSCN-Khaplang) have support bases within specific tribes (Phukon 2006:158). These are ground realities that will have to be confronted during any peace process. Nevertheless, the very survival of the Naga struggle over this long period has a logic of its own that has produced ‘a cohesiveness and a sense of unity which very few nationalities of the sub-continent can lay claim to’ (Misra 2000:16). At the end of 2006, the top leadership of NSCN-IM had arrived in New Delhi (from Amsterdam) for the fourth round of talks with the Indian government since 2003. Immediately upon arrival, the General Secretary declared that Nagalim would not be part of India. (Jha and Bhattacharya 2006, Bhattacharya 2006). The name Nagalim implies not only independence from India but the creation of Greater Nagaland, bringing under Naga control all parts of the north-east where Nagas live. The latter is a contentious issue for other ethnic groups in the region, as we will see later in this chapter.

Assam The ‘Assam Movement’ began in 1979 on the ‘foreigners’ issue with the updating of electoral rolls that declared almost 50,000 voters to be ‘illegal’ immigrants. Led by the middle class, it had a wide popular base both rural and urban, and sustained large-scale civil disobedience for several years, including a successful call to boycott the polls of 1983. The Indian state’s response was severe repression, and hundreds of Assamese lost their lives to state violence (Misra 2000:132-3). In 1985 the Assam Accord was signed between the Indian government and the movement, a broad settlement with clauses whose wording is revealing. There were to be constitutional safeguards to ‘protect, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people’; the Indian government committed itself to ‘the all round economic development of Assam’ and promised to establish advanced institutions of learning in science and technology (Baruah 1999: 115-6). The fact that such clauses, which should be the foundation of a healthy federal constitution, had to be negotiated at the end of a protracted struggle, tells us something about the nature of Indian federalism.

On the question of ‘foreigners’, the agreement was that they would be classified into a number of categories based on when they entered India, and either be given citizenship rights, temporarily disenfranchised or immediately deported. These measures however, can be implemented only arbitrarily because of the problems with determining year of entry, in the absence of legal documentation even for most bona fide citizens of India. Because of the logic of Partition it is assumed that Hindu immigrants from Bangladesh have a right to live in India, and so the driving out of ‘foreigners’ works in a sweeping anti-Muslim manner, because of the near-impossibility for Bengali-speaking Muslims to establish West Bengali rather than Bangladeshi origins. (Supposed Bangladeshis are periodically ‘flushed out’ from the slums of Delhi in brutal police drives.) The legitimation of the issue has served many political parties very well, especially the BJP. Indeed, the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) formed after the accord of 1985, which won the state assembly elections held thereafter, has had poll alliances in Assam with the BJP and has been one of the allies of the National Democratic Alliance. In 2006, the secretary of the AGP was one of the five persons who successfully challenged an order of the UPA government, the Foreigners (Tribunals for Assam) Order, in the Supreme Court. The order had placed the onus of proving a person ‘foreigner’, on the complainant. The striking down of this order by the Supreme Court means that the situation reverts to the 1964 Foreigners Tribunal Order, by which the person accused of being a ‘foreigner’ has to prove s/he is not one. As we discussed above, such proof is almost impossible to produce for the majority of even the legal citizens of India, and in effect, legitimises a form of ethnic cleansing.

Over the years, the AGP has lost much of its shine, its government performing poorly and becoming associated with the lavish lifestyles of its leadership, and with charges of corruption and nepotism. The promises made by the central government to Assam were also not kept, and the Assam Accord remained on paper. Assamese aspirations took a more militant turn with the coming to the fore of United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA), which had been formed at the beginning of the Assam movement, in 1979. It is an armed struggle for an independent sovereign Assam, Swadhin Asom. ULFA gradually distanced itself from the immigration issue, and began to make its appeal to Asombasi – that is, to all people ‘living in Assam’, rather than to ‘natives of Assam’. It puts forward the idea of a federal Assam where different ‘nationalities’ would possess maximum autonomy bordering on self-rule (Misra 2000; Baruah 1999). ULFA claims to represent ‘not only the Assamese nation but also the entire independent minded struggling peoples, irrespective of different race-tribe-caste-religion and nationality of Assam’.[8] ULFA is understood by some to have made a radical shift by the 1990s, from its position in the early 1980s, becoming influenced by Maoism, and attempting to give a leftist direction to Assamese nationalism (Gupta 1990; Mishra 1991).

However, a new aspect of ULFA’s ideology emerged when in July 1992, in a publication addressed to ‘East Bengal migrants’, ULFA identified not only the Indian state, but ‘Indians’ as the real enemy: ‘East Bengal migrants are to be considered Assamese…They…work hard for the betterment of Assam, sacrificing themselves for the future of the State. They are our real well wishers, our friends, better than the Indians earning at the cost of the Assamese people.’[9] These views were reiterated in the ULFA journal Freedom in December 2006 (Kashyap 2006). This campaign against ‘Indians’ has resulted in a number of targeted killings of poor migrants from Bihar and UP in Assam (for instance, episodes in 2003 and 2007) (Kashyap 2007 a). After the most recent killing, the vice-chairman of ULFA, Pradip Gogoi, in jail for over eight years now, reportedly held New Delhi responsible for stopping peace talks, and ‘provoking our boys’ (Kashyap 2007 b). [10]

Through the 1980s ULFA carried out military attacks on the Indian state and was banned by the Indian government in 1990. Since then it has functioned underground, and carries out activities such as bombing of economic targets like crude oil pipelines and freight trains; carrying out assassinations and guerrilla actions against government security forces. The AFSPA being in force in Assam, the armed forces of the Indian state act with complete impunity against the civilian population. In 2006 talks began between ULFA and the Government of India, but the latter has not addressed ULFA’s core demand, the suspension of army operations, while the question of sovereignty for Assam is a distant one (Prabhakara 2006). The talks ended in a stalemate.

The extent to which the idea of Swadhin Asom still captures the imagination of the Assamese people is a matter of sharp debate. Scholars like Udayon Misra at the end of the 1990s, perceived the ranks of ULFA as expanding despite government repression. He felt that ULFA had succeeded in recruiting from all sections of Assamese society, including the tribes traditionally involved with tea plantations, immigrant Muslims and plains tribals (Misra 2000:147). However, in January 2007, wide publicity was given in the media to a state-wide poll conducted by an NGO called Assam Public Works, reportedly including family members of ULFA cadre, which claimed that 95% of the people polled (24.5 lakhs in 9 districts), rejected the ULFA demand for Swadhin Asom (Kashyap 2007 c).

Manipur In 1999, the Manipur People’s Liberation Front (MPLF) was formed, bringing together the United National Liberation Front (UNLF), the oldest Meitei[11] insurgent group in the state, formed in 1964 with the goal of attaining independence from India; and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) founded in 1978.

The UNLF has training camps in Myanmar and Bangladesh. It is evident that political links between ethnic groups are being strengthened across national borders and that insurgent groups receive aid and training from the governments of Myanmar, Pakistan and Bangladesh, just as the Indian government does the same for insurgent groups from these countries.

Today in Manipur, there are up to 35 insurgent groups with various demands — independence, new states within India, greater autonomy, greater rights, territorial integrity or simply development on their own terms. Some groups are powerful enough to run parallel governments — imposing taxes and running administrative and judicial systems.

A new phase of the unrest in Manipur was inaugurated in 2001 by the extension of the 1997 cease-fire agreement between the Indian government and the NSCN-IM to all the states in which Nagas live. By thus extending the geographical reach of the ceasefire to Manipur, the Indian government in effect recognized Nagalim (Greater Nagaland), which would spell the end of Manipur as a state. There was large-scale protest directed largely at the Indian and Manipuri governments, (not at the majority Naga population) which was met by state repression. The movement has now grown into a powerful popular uprising against the AFSPA which shows no signs of waning even in 2006, its sixth year.

Two images of the unrelenting struggle of Manipuris against the AFSPA:

2006 The calm, challenging face of Irom Sharmila, with a feeding tube in her nose – she is under arrest, being force-fed by the Indian state. Sharmila has been on a hunger strike from 2000, for six continuous years, demanding the repeal of the AFSPA. On the expiry of her fifth consecutive one-year sentence for ‘attempted suicide’, she evaded police and flew out to Delhi, staging a dharna (sit-in) for several days, before being arrested again.

2004 A group of Manipuri mothers, having stripped themselves naked, confronting the armed soldiers at Kangla Fort in the capital Imphal, with a banner – Indian Army, Rape Us. The army had abducted a young activist Manorama, and her raped and tortured dead body was found some days later. The image of the women’s protest was to reverberate across the country, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh appointed a high-level committee to review the provisions of the AFSPA, and in 2006 the Jeevan Reddy committee recommended that the legislation be scrapped.

The deadly AFSPA however, continues to remain on the statute books of ‘the world’s largest democracy.’

Ethnic identity and conflict

The second axis of conflict in the region is along the lines of ethnic identity. According to the 2001 census, about one-quarter of the population of the region is tribal, and in four states (Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh), tribal people are in the majority. We have discussed the term ‘tribe’ earlier.[12] It is a controversial one, because often it has a pejorative connotation of primitivism, head-hunting and so on. However, it is also the self-definition of politicised groups in this region, and an indicator of a claim to being indigenous, and therefore must be taken seriously. Levels of land alienation are very high among tribals, due to indebtedness or because it is sold for purposes such as educating children who remain jobless. Conflict over access to resources due to the high dependence on agriculture, high levels of land alienation and lack of other avenues of work, has increasingly taken the form of ethnic conflict.

It is also important to note that the tension in the area between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples does not necessarily correspond to that between tribal/non-tribal. The non-tribal Assamese of the Brahmaputra Valley and the Meiteis of Manipur also assert their rights as indigenous people, while the Hinduised Assamese in turn, face opposition from the Bodos, a tribal people from the plains of Assam who claim to be the original inhabitants (Baruah 1989:2087).

The Manipur insurgency too has turned against ‘outsiders’ – the minority Muslim Meitei, who became in the 1990s, the target of a wave of progroms. They have in turn received support from Pakistani and Bangladeshi intelligence services in forming fronts such as Islamic Revolutionary Front or Islamic National Front (Egreteau 2006: 64).

A long history of land acquisition by the Indian state for private tea estates, for the extraction of petroleum, uranium and natural gas and for defence installations, as well as generally low levels of economic development in the neighbouring region, has led to two phenomena: One, very high levels of migration into India’s north-east from other parts of India and from across the border, particularly from Bangladesh. The immigration is of two kinds, of labourers (Bangladeshi immigrants are largely illegal and mainly labourers) and of educated middle classes, the latter forming powerful immigrant communities in supposed ethnic homelands – for example, Bengalis in Assam. The second phenomenon is the gradual transfer of land from the indigenous people to the wealthier immigrants.

Thus, as mentioned earlier, the claim to indigenous identity has come to play a central role in the politics of this region because of the need to lay claim to local resources. Every successive immigrant group, whether labourers, plantation owners, or North Indian and Bengali middle classes, inevitably therefore, are perceived as a threat to the culture, and to the political and economic claims of indigenous people. Different groups assert different dates as cut-offs to establish indigeneity – the British-Burma treaty of 1826, the year of Independence 1947, or the date of the first census, 1951. Whatever the date for which recognition by the Indian state is sought, those who come afterwards are defined as alien, and ethnic conflict has become endemic here. Many conflicts such as the Naga-Kuki conflict in Nagaland and the Naga-Meitei conflict in Manipur are all about land and exclusive control over depleted resources, as land increasingly becomes the only reliable long-term capital (Fernandes 2006; Oinam and Thangjam 2006:66).

Similarly, as we have seen above, the claim to a ‘greater homeland’ for the Naga peoples, to bring all Naga-dominated areas in the northeast under one administrative mechanism, comes into conflict with other ethnic groups in Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. These resist the ‘expansionist’ politics of NSCN-IM. Until NSCN’s demand for Nagalim, it had been the rallying point for other insurgent outfits of the region, but now there are violent clashes between NSCN-IM and its former allies, especially ULFA. On the other hand, the Indian government’s decision to recognize Nagalim de facto through the extension of the ceasefire agreement, can only be seen as an attempt to further dissension among ethnic groups in the North-East.

In Meghalaya, the politics of Khasi identity emerged during the Assam movement. The anti-foreigner thrust of the movement was taken up by the Khasi Students’ Union (KSU, formed in 1978), but the focus was also on non-Khasis in general. In the 1980s and 1990s KSU led agitations around the core issue of control of the economy, polity and land by the ‘natives of Meghalaya’, the Khasis. Naturally, this aroused suspicion and fear among other tribes (Jaintyas and Garos) and non-tribal communities living in the state. In 2005, a demand by the Khasi leadership to restructure the Meghalaya Board of School Education (MBOSE), whose head office is located in the Garo Hills, was opposed by Garo organizations. The protests culminated in police firing resulting in the death of nine Garo protesters. The apparently innocuous issue of restructuring the MBOSE is thus revealed to be implicated in the politics of ethnicity – the KSU demand for bifurcation would split control of MBOSE between the Garo and Khasi-dominated parts of Meghalaya. Not surprisingly, the conflict escalated into demands for the bifurcation of Meghalaya – one for the Garos, another for the Khasis and Jaintyas (Talukdar 2005).

One of the demands of KSU is the introduction of the Inner Line Regulation system to Meghalaya, which would restrict entry of ‘outsiders’ into the state.[13] The system currently operates in three states – Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Mizoram. This demand on the part of KSU is of a piece with the increasingly xenophobic tenor of many groups in the region. The North East Students Organization (NESO), a joint platform of eight powerful student bodies (from all the seven states, including both the KSU and the Garo Students Union from Meghalaya) in 1992 presented the central government with a charter of demands to take strong action against illegal immigrants. The fears expressed are typical of homogenizing nationalisms on the way to becoming nation-states: ‘the sheer number of illegal immigrants in all the North-Eastern states threatens to undermine our societies – socially, culturally, economically, and above all, politically’; the immigrants marry local Naga girls, and the children of such marriages pose a serious threat to Naga life and culture; Myanmarese ethnic Mizos who enter Mizoram are responsible for ‘about 80 per cent of the crimes committed in the state.’[14] The KSU is actively involved in eviction drives of Bangladeshi nationals and in 2006 NESO demanded the scrapping of the Indo-Nepal Friendship Treaty, which it claimed was a cover for illegal immgration.

At the same time, NESO is active in the campaign against AFSPA, and supports the formation of a northeast trade zone which would enable trade between the region and Southeast Asia, in particular China, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Thus, it seems the movements in the region are replicating the logic of the nation-state and the notion of the sanctity and integrity of national borders, the very logic against which their struggles began in the first place. As Bimol Akoijam puts it, ‘the region called the North East of the postcolonial Indian state…is a theatre’ in which the actors can only ‘make sense of each other in terms of an intelligible shared world of colonial modernity’ (Akoijam 2006: 117), that is, the world of clearly bounded, homogeneous nation-states.

In this context, even an ecologically sensitive political imagination can co-exist with ethnic jingoism. Sanjay Barbora discusses the ‘crusading ecomilitancy’ of an armed ethnic militia of the Karbi tribe which issued a two-year ban on felling of bamboo and the use of pesticides in the Karbi Anglong area. Yet this group has been allegedly behind violence between Karbi and Kuki farmers. Barbora sees this as the outcome of a dual process of impoverishment and militarization, where small communities have to arm themselves to prevent a complete assimilation of lifestyles, culture and resources (Barbora 2006: 3808).

‘Conflict management’ in the North-East

Apart from military repression and playing off different militant groups against one another, the Indian state has also been pumping in disproportionately large sums of money into ‘surrender schemes’, which are meant to bribe militants away from violence. This is not accompanied by any infrastructure development or long-term planning. These funds therefore feed into a flourishing underground economy created by decades of armed conflict and militarization, involving smuggling, extortion, counterfeit currency, drug trafficking and arms dealing – a whirlpool into which everyday life in the region tends to get sucked.

The ‘management’ of conflict in the North-East has meant increasingly, argues Sanjay Barbora, policy interventions on the guidance of international funding agencies like International Fund for Agricultural Development. The new transformative concept promoted by transnational donor agencies is ‘ethnodevelopment’, supposedly a model that addresses the specificities of ethnic cultures and encourages them to join the global market. In this region, ending the practice of jhoom cultivation is one of the goals. This means the ending of community ownership of jhoom land, understood by bureaucrats to be incompatible with any form of rational agriculture, and the institution of individual property rights. The outcome is bound to be greater inequality between people of even one ethnic community, apart from accentuating inequality between less and more numerous or powerful groups (Barbora 2002).

Similarly, experiments in coffee, tea and rubber cultivation were initiated in the 1980s by the Indian government, which consolidated lands for plantations by getting villagers to pool in common land, which was then placed under the supervision of a manager, usually a non-tribal. In the late 1990s when the prices of coffee fell in the global market, the government bodies withdrew, leaving ‘ghost plantations’ dotting the hills (Barbora 2002).

The striking features of politics in the region then, are continuing insurgency, extreme state repression and consequent overall militarization, the bureaucratized micromanagement of the economy under the tutelage of international funders and the limitations of what Sanjib Baruah calls the ‘homelandist’ imagination (Baruah 2005).

Baruah makes an argument for an ‘alternative institutional imagination’ to end the ‘durable disorder’ of the North-East. This alternative imagination would disentangle identity from a territorially and ethnically rooted collectivity. He urges that the ethnic homelands of the region be dismantled by giving citizenship rights to the large numbers of ‘illegal’ immigrants, and more importantly, that the North-East develop its relationship with its eastern neighbours (Baruah 2005b). Currently such an alternative imagination it is certainly not the dominant vision visible on the horizon, either of the Indian state or of the insurgent movements.

Jammu and Kashmir

Insurgency in Kashmir, as with many states of the North-East, cannot be understood without going back to the question of accession to India in 1947. Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is the only Muslim majority state in India, being roughly half of the territory called Jammu and Kashmir before 1947. About a third of the pre-1947 J&K is under Pakistani administration; an area called, respectively by the Indian and Pakistani governments, Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK) and Azad Kashmir (Free Kashmir). The remaining part is controlled by China – Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract (Shaksam Valley), which was ceded by Pakistan in 1963.

J&K has three regions with specific profiles in terms of religious identity – Kashmir Valley is predominantly Muslim, Jammu predominantly Hindu, and Ladakh largely Buddhist. This particular demographic feature of J&K is also increasingly becoming relevant to understanding its politics.

In August 1947, under the Indian Independence Act, the 600-odd Princely States had three options – accession to India or Pakistan, or independence. Most acceded to India, but those that did not were annexed, as we saw earlier with Manipur. In the context of Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state with a Hindu ruler, it is instructive to consider the case of another Princely State, Junagadh, a Hindu-majority state with a Muslim ruler, who decided to accede to Pakistan. However, on the grounds that a Hindu-majority state could not be part of Islamic Pakistan, the Indian government annexed Junagadh and in December 1947, it held a plebiscite in which predictably, the Hindu-majority population overwhelmingly voted to be part of India. The question of a plebiscite thus hung over Kashmir too, but India never considered one at this stage.

The ruler of Kashmir Hari Singh had ambitions of Kashmir being an independent state, and in this was backed by the largest political party in the state, National Conference (NC) led by Sheikh Abdullah. He had therefore not taken a decision on accession until August 1947. In September however, Pakistan permitted incursions into Kashmir by tribesmen from the North-West Frontier, soon afterwards backing them with regular forces. Hari Singh had to turn to India for assistance, which was given on the condition that he sign the Instrument of Accession. Thus began the first war between India and Pakistan, which ended with a ceasefire in 1949, outlining what has come to be called the Line of Control (LoC), the de facto border between the two countries.

Two more wars were fought between India and Pakistan – in 1965 over J&K and in 1971, when India militarily backed the formation of independent Bangladesh. The Simla Agreement that ended the 1971 war, defined the LoC in Kashmir and committed both sides to future bilateral negotiations. At this point India took the position that UNSC Resolution 47 was no longer valid, while Pakistan still formally insists on a plebiscite as do some militant groups in Kashmir.

If we are interested in understanding Kashmir however, we must go beyond treating it as merely a ‘territorial dispute’ between two nation-states as they race for greater control in the subcontinent. What do Kashmiris want? And is it possible to arrive at any reliable answer, given the extremely vitiated circumstances in that troubled state?

The run-up to the 1990s

The Instrument of Accession gave J&K a special status. It has its own constitution, and its legislature must adopt laws passed by the Indian Parliament for them to become applicable in the state. It was also guaranteed autonomy in all affairs except for foreign policy, defence and communications. However, this autonomy has remained on paper, and its special status has been gradually eroded by the Indian state through constitutional amendments.

By 1964, constitutional amendments were passed that brought J&K under the strongly unitary umbrella of Indian federalism, rendering void almost all the provisions of Article 370, which gave the state a large degree of autonomy. One of these amendments ensured that the Governor of the state, hitherto elected by the state assembly, was now to be nominated by the Centre. While the Governor is in principle under the control of the democratically elected assembly, the extension of specific articles of the Indian constitution to J&K meant that as with other states of the Indian Union, the central government could dismiss the state government, impose President’s Rule and run the state through the Governor whenever necessary.

It is important to remember that the accession to India was conditional, subject to ‘a reference to the people’ as soon as the invaders had been removed. According to Balraj Puri, this condition was necessary to overcome Hari Singh’s reluctance to accede to India, and moreover, it was this principle of ‘the people’s will’ that enabled India to annex two other states, Junagadh, which we have discussed, and Hyderabad (Puri 1993: 14-15). In other words, the accession itself was conditional on the holding of a referendum. However by 1957, the Indian government took the position that since the Instrument of Accession had been ratified by the state’s Constituent Assembly and by two consecutive legislative assemblies, the required ‘reference to the people’ had been conducted and J&K was now an integral part of India. However, this ‘ratification’ must be seen in the light of the fact that in the two elections to the state assembly that took place during this period, parties supporting plebiscite were not allowed to participate, and it is generally accepted that there was large-scale rigging by forces propped up by the Indian government, to ensure a pliable legislature (Puri 1993: 45; Behera 2000: 114; Joshi 2002).

The logic of the nation-state operated in the realm of the economy as well, a feature we have discussed with reference to other aspects of Indian politics – in the North-East and with big dams, for instance. J&K’s rich natural resources in forests and water have served to develop Indian capitalism. Extensive deforestation served to provide cheap timber for the Indian railways, while Kashmir’s water resources are fully under the control of the centre. All the key power projects in the state were taken over by the National Hydel Power Corporation, so that while Srinagar would be without power three days in the week, power from the state was being provided to the northern grid of India, Delhi being the largest consumer. Investment by Delhi in the state has basically been in two fields – roads/communication and power generation/transmission – the better to ensure commercial exploitation and military control. There has been virtually no investment in the field of industry (DN 1991).

Through the 1950s and 1960s, the Indian state clamped down on all forms of democratic protest in the state, treating demands for genuine autonomy as secessionist, jailing Sheikh Abdullah in 1953, as well as many other leaders.

The political movement for plebiscite and for the release of Sheikh Abdullah continued unabated until in 1974, the Kashmir Accord was signed between the NC and the Indian government. While it offered much less autonomy than the state enjoyed prior to the developments described above, it was nevertheless welcomed, especially as Sheikh Abdullah was released and he returned as Chief Minister. The revived National Conference won sweeping victories in the assembly elections of 1977 and 1983 (under Sheikh Abdullah’s son Farooq), generally accepted as the fairest ever held in Kashmir. For a decade after the Kashmir Accord, groups that stood for azadi (freedom for Kashmir) and pro-Pakistan voices were marginalized.

However, the 1983 General Elections were marked by the general trend towards communalisation becoming evident in India at that time. The Congress campaign in J&K overtly appealed to Hindu sentiments in order to marginalize the growing challenge offered by the Hindu right, while Farooq Abdullah’s victory in J&K had been crafted in an alliance with an Islamist party, Awami Action Committee. Although the agenda of the alliance was not Islamist but the ‘preservation of Kashmiri identity’, Farooq Abdullah posed a challenge to the Congress because he presented the elections as a referendum on who should rule Kashmir – New Delhi or its own people (Behera 2000: 150). Soon afterwards, the NC hosted a conclave of opposition parties. Such insubordination was not to be tolerated, and in 1984 the Congress Party in power at the centre dismissed Farooq Abdullah’s government The successor government too was dismissed in 1986, and President’s Rule imposed on the state. By the time of the 1987 elections, Farooq Abdullah having learnt his lesson, entered into an electoral alliance with the Congress. The 1987 elections are a landmark in the history of J&K, and signal the beginning of a period of renewed insurgency and state repression that cannot be said to have ended even today.

Abdullah’s compromise with the Congress Party was seen as a betrayal by Kashmiri voters, already disillusioned by the corruption and incompetence that marked his previous regime. There was growing support for a new party, the Muslim United Front (MUF), a coalition of Islamic and pro-azadi parties. However, the NC-Congress alliance came to power through a process marked by mass arrests of MUF candidates and party workers, and vote-rigging on a massive scale. Electoral politics in Kashmir was revealed to be a sham, and as democratic forms of protest became impossible, thousands of young men crossed the border to Pakistan, received training and arms, and returned to inaugurate a new phase of large-scale violence.

Militancy in the 1990s and beyond

From 1987 to 1990 the Farooq Abdullah government faced growing economic crisis and an overall failure of legitimacy. There was increasing opposition to his government not only from militants, but from the people of Kashmir, which was met with extreme police repression. The centre appointed Jagmohan as Governor and Abdullah resigned in protest, as Jagmohan had been involved in the earlier dismissal of his government. The state came under President’s rule again.

Navnita Chadha Behera outlines five phases of the insurgency from 1988 to about 1996 (Behera 2000). The first phase (1988-90) involved the underground militant movement which evolved into a mass political movement. The Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) [15] with its agenda of an independent Kashmir, set up a unit in J&K in 1988. It successfully mobilised violent protests around issues that ranged from hikes in power tariffs to Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, protests that could paralyse the state apparatus and that widely delegitimised political institutions. Assassinations, attacks on police stations and officials, and attacks on NC members (seen as a pro-India force in the Valley) were routine.[16] The 1989 elections were boycotted. The daughter of the Union Home Minister, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed was kidnapped, and the release of five JKLF militants demanded. The government met the demand, and the returning militants were met with an explosion of joy in the Valley, the jubilant crowds certain that azadi was round the corner.

Governor Jagmohan’s policy was to crush the movement with armed force. ‘The bullet is the only solution for Kashmiris,’ he said in an interview. He started his first day in office with 35 dead in police firings and over 400 arrested (Behera 2000: 169, 206). The infamous Gawkadal incident, in which large numbers of unarmed civilians were killed by security forces, transformed the underground militant campaign into a mass movement. There was a near-total uprising of the entire population. Tens of thousands, including children, marched daily on the streets to the cry of azadi – many of them government employees, often marching behind the banners of their departments. Shoot-at-sight orders and long spells of curfew, often lasting for weeks, became the order of the day (Puri 1993: 61). Refusing to recognize the mass character of the uprising, the Indian government termed it Pakistan’s ‘proxy war’, thus justifying the draconian measures it used to quell the rebellion.

The JKLF, at the forefront of the movement in this phase, represents a secular vision of Kashmiri nationalism which foregrounds ‘kashmiriyat’ or Kashmiri-ness. Its aim is to liberate and reunify the state of J&K as it existed prior to Indian and Pakistani independence.[17]

The second phase (1991-2) saw the JKLF losing its leadership role, partly because much of its leadership was killed or imprisoned by the Indian state, and partly because Pakistan began to withdraw support to it because of its agenda of independence. Instead, pro-Pakistan and Islamist groups were raised, the most prominent being Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), its political patron being Jamaat-i-Islami. HM backed by Pakistan, attacked and depleted JKLF cadres and the uncomfortable alliance between JKLF and Pakistan fell apart. HM’s women’s front in Kashmir Valley, Dukhtaraan-e-Millat, publicly supported the ultimatum that Muslim women should wear a burqa,[18] issued by another such group Lashkar-e-Jabbar in 2000. However, HM’s strict adherence to Islamic ideology is not popular in the Valley, where sufi traditions are prevalent. In fact this Muslim-majority state has among the lowest enrolment figures in the country for madarsas, where traditional Islamic teaching is imparted (Rashid 2006).

From the early 1990s there has been a virtual exodus of Kashmiri Hindus (called Pandits) from the Valley. While this is attributed by many to the questionable role of Governor Jagmohan who encouraged their departure in order to sharpen the sense of crisis in Kashmir, there is no doubt that HM and other organizations are also responsible for creating an atmosphere of terror for the Hindu minority. Targeted killing of Hindus has been common since the 1990s. The BJP has contributed to this agenda of communal polarization by systematically sabotaging attempts at joint community initiatives to counter HM and instead, creating armed ‘village defence committees’ in Hindu dominated areas.

The third phase began in 1993 with the siege by Indian security forces of Hazratbal mosque and the surrender of militants. It is around this time that the conflict in Kashmir begins to get inserted into the larger politics of global Islam. New connections begin to be made. Pakistan too, presumably saw an opportunity here to encourage Afghan and other foreign mercenaries of global Islam to enter the scene. This changed the character of militancy in the Valley. Kashmiriyat was relegated to the background and the struggle in Kashmir became just one part of a global Islamic movement. Among the prominent groups of this sort is Harkat-Ul-Ansar, an international network of Muslims, whose members are committed Islamic militants.

The growing disillusionment of the people with these transformations of the militant movement led to the fourth phase (1994-5), in which there was growing opposition from the people to the Islamization of the movement and determined efforts to regain Kashmiri control. There were incidents of massive public reactions against HM’s criminalization of Kashmiri politics and its attempts to suppress ancient Kashmiri practices and festivals (Behera 2000: 188, 191). For their part, Kashmiri militant groups made an attempt to regroup. The All Party Hurriyat Conference (APHC) comprising about 30 political groups was formed. Led by the Mirwaiz,[19] whose father had been assassinated by HM, the Hurriyat has an Islamic orientation, and its constituents’ demands ranged from independence to union with Pakistan. Like the JKLF, it rules out a settlement within the framework of the Indian constitution, is for plebiscite, and its constitution is committed to a peaceful struggle for self-determination.

The Hurriyat split in 2003 into what in India is called the ‘moderate’ faction under the Mirwaiz, which has links with JKLF, and the more ‘hardline’ pro-Pakistan faction led by SAS Geelani.

In 1994, the JKLF leader Yasin Malik was released, and he announced that JKLF would renounce violence and henceforth adopt Gandhian means. He announced a unilateral ceasefire and his preparedness to hold talks with the Indian government. Malik also declared Kashmiri Hindus to be an integral part of Kashmir, and urged them to return (Sharma 2004).[20]

India and Pakistan in Kashmir

By 1995-6 the Kashmiri component of the movement was in decline, and the Indian government was successful in initiating counter-insurgency through surrendered militants as it has in the North-East. From 1990 there have been laws in place – the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act and the Jammu and Kashmir Disturbed Areas Act – that give armed forces and security agencies unlimited powers of detention and interrogation. Human rights violations on a massive scale have been extensively documented – summary executions, custodial killings, torture, ‘disappearances’, arbitrary detentions, regular warrant-less searches usually in the middle of the night, attacks on civilians as retaliation for militant attacks, indiscriminate firing on unarmed demonstrations.[21]

Meanwhile, foreign mercenaries operate openly out of Pakistan, seldom claiming responsibility for attacks and kidnappings, many of which have been on civilians, often foreigners. It is common for them to change their names periodically, particularly after they are banned (Human Rights Watch 2006: 23-24).

In 1999, in the escalation of tensions following India’s nuclear explosion in 1998, Pakistani troops and militants occupied parts of Kargil in J&K. The Indian state responded with force, and the Clinton administration stepped in to defuse the situation, getting Pakistan to withdraw. Later that year, militants hijacked an Indian flight to Afghanistan and secured the release of three Pakistani militants. Since September 11, 2001, Pakistan has been successfully pressurised by the US to withdraw support to militancy in Kashmir and according to Indian sources, there is a trend of decreasing infiltration over the years since then.

The 2002 Elections

In 2002, elections to the J&K state assembly were held, whose conduct was perhaps the fairest in its history, partly because they were held in full international and national glare, with observers from the European Union as well as scores of citizens’ groups from the rest of India, monitoring them. However, since Kashmiri nationalists and separatist groups refused to participate in elections under Indian supervision, the extent to which the current government, a coalition led by Mufti Mohammed Sayeed of People’s Democratic Party, represents the will of the people is in question. The voter turnout was only 48% (the national average is about 65%), but Praful Bidwai suggests that the picture is more complex than the rival claims made by India and Pakistan. The NDA government’s claim was that that the successfully conducted elections were a victory for India’s refusal to talk to hardliners, while Pakistan dismissed the elections as a farce. Bidwai argues against the Pakistani view by pointing out the high level of interest in the elections, with crowds of thousands turning out for campaign meetings. It is also significant that the voter turnout was as high as 77% in the overwhelmingly Muslim-majority districts near the LoC. The number of candidates filing nominations rose by 30% from 1996, and a host of small parties focusing on local issues, participated. However, in response to hawkish pronouncements from India that these elections showed there was no longer any need for dialogue with Pakistan on Kashmir, Bidwai points out that contesting these elections cannot be seen as supporting New Delhi’s policies because many candidates stood on a platform of azadi. But more importantly, he cites a report of Coalition of Civil Society, a group of NGOs that monitored the elections, which asserts there was widespread coercion by security forces to ensure voting, although not to vote for a particular party.

Based on observers’ reports and informal interviews, Bidwai concludes that while the elections were not seen by the Kashmiri people as a referendum on the Indian government’s policies, Kashmiris are exhausted by the spiral of violence produced by externally-sponsored militants and the Indian state. Many believed that a new J&K government could protect them from growing confrontation between these, while addressing everyday grievances about water, roads and jobs.

In addition, Farooq Abdullah’s NC had lost all credibility, being widely seen as corrupt, unresponsive to people’s basic needs, and opportunist in allying with the BJP. Many may have voted just to remove the NC from power. Says Bidwai, ‘Islamabad is thus wrong to dismiss the elections. And New Delhi is equally mistaken to see them as a substitute for a genuine broad-based dialogue both within India and with Pakistan’ (Bidwai 2002).

In 2003 India and Pakistan announced a cease-fire at the LoC, ending almost a decade of continuous exchange of fire. The previous PM of India began talks with general Musharraf of Pakistan, and the current UPA government is also committed to the peace process.

Regional autonomy and communalism within J&K

Ascertaining the ‘will of the people’ of J&K is complicated by growing differences between the three regions of J&K. Since the demography of these regions also corresponds to religious identities – Kashmir Valley has a majority of Muslims, (95%), Buddhists comprise 50% of the population of Ladakh and 66% of Jammu is Hindu – demands for trifurcation of the state along religious lines have of late been propagated by Hindutva forces. However, fighting elections on this plank, the BJP and the RSS-Jammu State Morcha alliance were trounced in the 2002 elections.

But demands for greater autonomy made by Jammu and Ladakh have a longer history independent of national-level communal politics, that can be traced back to the 1950s (Behera 2000: 215-247). There was disappointment in these regions after the 1987 elections, when the NC failed to keep its commitment to appoint a commission to look into regional autonomy (Puri 1993: 54). After its victory in the 1996 elections, the NC once again promised to build a federal structure, with regional autonomy for Jammu, Ladakh and Kashmir, and ‘sub-autonomy’ for ethnic and religious groups in these regions. However, the controversial report of the Regional Autonomy Committee (RAC) set up by Farooq Abdullah in 1999 recommended the sharp division of each region along religious lines with no real devolution of power. This was widely perceived both as a communal move and as a tactic to stall the process of internal autonomy.

It would be naively optimistic not to recognize the communalisation of regional aspirations in J&K especially since 1989, in keeping with general developments in the subcontinent. Ladakh has witnessed the emergence of modern communal politics at the electoral level, as well as violent clashes between the Buddhist and Shia Muslim communities. In 1990 some Kashmiri Pandits formed the organization Panun Kashmir (Our Own Kashmir), demanding a secure zone in the Valley in which the Hindu population could be concentrated. This would be a homeland, they claim, for internally displaced Kashmiris, who ‘mostly happen to be Hindus’, who have ‘faced oppression for centuries’ (Behera 2000: 231). This demand is not supported by the Pandit community as a whole however, who are spread out throughout the valley, and do not wish to be herded into a ’homeland.’ Nor is Panun Kashmir the only organization representing the community. Although most organizations of Kashmiri Pandits are understandably formed on a platform marked by the enforced departure of the community from the Valley, at least one organization of Pandits, the older All India Kashmiri Pandit Conference, has recently begun initiatives to work with Kashmiri organizations such as Hurriyat towards bringing about peace in the state (PTI 2002).

In addition, the Kashmir valley has seen over the last decade, the development of Islamic sectarianism that has taken violent forms. Following an attack on a saint in 2005 and the killing of worshippers in 2006, an initiative has been taken by the Jamaat-i-Islami to start dialogue among different sects, so that their differences may not be ‘exploited for political ends’. The fact that the initiative has come from the Jamaat is perceived as significant because it has stood so far for strict Islamic practices. [22]

Despite the emergence of communal politics however, there is undoubtedly a need for genuine autonomy for the regions in keeping with federal principles. An alternative proposal was formulated by Balraj Puri who had initially been appointed working chairman of Farooq Abdullah’s Regional Autonomy Council (RAC) and later dismissed. Puri recommended the recognition of regional identities as the best guarantee of secularism, and recommended a five tier system that included devolution of power from state to region to district, block and village level (Chowdhary 2000). Significantly, JKLF too envisages a democratic and federal system for independent Kashmir in which each of the five federating units (Kashmir Valley, Jammu, Ladakh, Azad Kashmir, and Gilgit & Baltistan) would enjoy internal autonomy. Indeed, under the present circumstances, many feel that regional identities can be ‘an alternative rallying point’ to communal identities (Watt 2002).

The ‘Kashmir Question’ at the end of 2006

In 2005, according to the terms of the Congress-People’s Democratic Party (PDP) coalition that won the 2002 elections, Ghulam Nabi Azad of the Congress Party became the Chief Minister of J&K replacing Sayeed of the PDP. By the end of 2006, the coalition appeared to be in trouble, with PDP declaring itself ready for mid-term polls. The tussle over leadership is at one level a reflection of regional differences – Azad being from Jammu and Sayeed from the Kashmir valley. But there are more fundamental differences between the two parties on autonomy for J&K – the Congress wants the 1975 Kashmir Accord as the framework, while the PDP turns to the pre-1953 status. The PDP is thus committed to talks with separatist forces such as the Hurriyat Conference, which the Congress will not accept.

During the two round-table conferences on J&K called by the Indian government in 2006, no attempt was made by Indian authorities to involve groups that question accession to India. Indeed, the Prime Minister’s opening statement made it clear that ‘a common understanding on autonomy and self-rule in Jammu and Kashmir’ would have to be evolved ‘within the vast flexibilities provided by the constitution’ (Navlakha 2006: 947. Emphasis added). Such intransigence on the part of the Indian state accompanied by the continuance of extraordinary laws empowering security forces, does not bode well for a democratic resolution that represents the will of the people of J&K.

Today the Kashmir Valley remains a heavily militarised area with the visible and intimidating presence of hundreds of thousands of army, paramilitary and police forces. The pressure on these men too, is evidently close to unbearable – since 2002, there have been about 400 suicides by soldiers, while about a 100 have been shot by colleagues in ‘fratricidal’ fights related to stress (Special Correspondent 2006 b; 2006 c).

In Arundhati Roy’s words, ‘…Kashmir is a valley awash with militants, renegades, security forces, double-crossers, informers, spooks, blackmailers, blackmailees, extortionists, spies, both Indian and Pakistani intelligence agencies, human rights activists, NGOs and unimaginable amounts of unaccounted for money and weapons…Truth, in Kashmir, is probably more dangerous than anything else’ (Roy 2006: 74).

Roy raises the question of truth in the context of the current controversy over the Supreme Court’s awarding of the death sentence to Afzal Guru, implicated in the attack on the Indian Parliament on December 13, 2001. The attack was foiled by security forces. Six policemen and a gardener were killed in the exchange of fire, as were all five militants, alleged to be linked to Pakistan-based organizations active in Kashmir. India began to deploy troops to the border, as did Pakistan. As nuclear conflict loomed, international pressure pulled back both sides. The attack enabled the NDA government to re-promulgate the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Ordinance and subsequently to pass it in an extraordinary joint session of parliament as the Prevention of Terrorism Act in March 2002. This legislation had been severely criticized for its violation of civil rights, and influential public opinion had been building up against it prior to December 13th.[23]

Questions began to be raised by concerned citizens about the timing of the attack on Parliament, the unsustainability of the prosecution argument and the callous disregard for the rights of those accused of participating in the conspiracy (the actual perpetrators were of course, all killed). In an article published in 2004, later extended into a book, Delhi University professor Nirmalangshu Mukherji raised serious doubts, meticulously documented, about the genuineness of the attack itself.

Afzal Guru is a surrendered militant who was in constant contact with, and under the surveillance of, the Special Task Force of the J&K police when he was arrested for the parliament attack. After he received the death sentence in 2006, a public campaign to reveal the truth about December 13th has grown in strength. The barely veiled question being asked with greater confidence is : was the attack actually stage-managed by the Indian security forces with backing from the political leadership, who used the incident as a pretext to carry out massive military mobilization on the Indo-Pakistan border, pushing the subcontinent to the brink of nuclear war? This question becomes stronger in the face of extensive documentation of the collusion of influential visual and print media in purveying police versions discredited by the courts.

The campaign includes a petition for clemency for Afzal, not only because the campaigners are opposed to the death penalty itself, but because the Supreme Court judgement clearly concedes there is no evidence against Afzal. Despite this, the judgement goes on to say, ‘The incident…has shaken the entire nation, and the collective conscience of the society will only be satisfied if capital punishment is awarded to the offender’ (Mukherji 2004; Mukherji 2005; Roy 2006; Noorani et al 2006).

Public opinion in the country is thoroughly polarized on the issue. For many, those who want clemency for Afzal represent nothing less than the enemy inside. The family members of the policemen who died on December 13th have returned their medals for gallantry in protest at the sentence having been deferred. That Afzal – representing a state and a people that have doggedly eluded the grasp of the Indian nation – should be still alive at the end of 2006 has become for many, a symbol of the deepest injustice. When a demonstration by visually handicapped people in Delhi for their demands was lathi-charged by the police, their posters the next day read – andhon ko lathi, Afzal ko maafi? – beatings for the blind but pardon for Afzal?

Here is a tragic irony – the blind competing with the ‘terrorist’ for the mercy of the state – the first utterly marginal to the nation, the second central to its constitution.

December 13th 2001 and its aftermath represents another moment in that never-completed project of producing a nation. Another attempt to assuage what Ranabir Samaddar terms a ‘particular kind of post-colonial anxiety’ – the anxiety of ‘a society suspended forever in the space between the “former colony” and the “not-yet nation”’ (Samaddar 1999:108).

[1] Here we use the well-known title of the book by Sunil Khilnani The Idea of India Penguin Books, 2003.

[2] Of course, the classic process even in Europe was forceful and authoritarian. French historian Eugen Weber starkly terms it as ‘akin to colonialism.’ This is how he describes the ‘acculturation’ process in the 19th century by which the inhabitants of the area that became France were made ‘French’: ‘the civilization of the French by urban France, the disintegration of local cultures by modernity and their absorption into the dominant civilization of Paris…Left largely to their own devices until their promotion to citizenship, the unassimilated rural masses had to be integrated into the dominant culture as they had been integrated into an administrative entity. What happened was akin to colonialism…’(Weber 1976:486).

[3] ‘Princely States’ were kingdoms, many of ancient lineage, and with a long history of exercising political power. It was British colonial terminology that referred to the rulers as ‘Princes’. While the quasi-independent status they enjoyed under British rule made them hostile to the anti-imperialist nationalist movement, some of these kingdoms had enlightened rulers with agenda that were in many cases more progressive than that of the British government.

[4] It was an LTTE suicide bomber who assassinated Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991.

[5] We are thankful to MSS Pandian for a conversation on this last point.

[6] ULFA is United Liberation front of Assam and NSCN-IM is National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isaac- Muivah). Both organizations are discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

[7] See Homepage of ULFA http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Congress/7434/ulfa.htm. Downloaded on December 10 2006; and Homepage of NSCN http://www.nscnonline.org/nscn/index-2.html downloaded on December 25, 2006.

[8] From the Homepage of ULFA http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Congress/7434/ulfa.htm. Downloaded on December 10 2006.

[9] Translation of ULFA leaflet, ‘Ahombashi Purbabangiya Janaganaloy’, Sanjukta Mukti Bahini Ahom, 1992, by Bhibhu Prasad Routray, ‘ULFA. The “Revolution” comes full circle’, available at http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume13/Article6.htm.