‘Sayeen, ham nay toh kabhee 5,000 banday kaa jaloos bhi nahee nikaala. Siyaasat kay liyay aik laash kya, aik zakham bhi nahee hay hamaray paas toh. Aur aaj lag aisay raha hay kay hamaari dheemi dheemi baaton ko sun kar yay Punjab kay tukray karnay lagain hain’ (Sayeen, we’ve never taken out a rally with 5,000 people. Forget martyrs, we don’t even have a bruise to flaunt for political mileage. And today, it seems they’ve heard our whispers and taken them to heart. Today, they’re talking about splitting Punjab.)

While talking to a few last month, I realized that most independent Seraiki activists privately acknowledge that the issue of a new province, or at the very least, a wholesale recognition of Seraiki grievances, was a cause that could only be made actionable when the People’s Party thought it to be worthwhile – and 9 times out of ten, a cause’s worth for a national level party is determined by its weight in the electoral matrix.

Firdous Ashiq Awan, in her characteristically blunt, Sialkoti way, thankfully spelt it out in fairly simple terms: a party that doesn’t support the creation of South Punjab runs the risk of becoming politically irrelevant in one half of the province. Even in other statements, by other leaders, it’s quite obvious that such provocations are directed towards the PML-N, given how they’ve remained confined to Punjab over the last 3 years. For PML-N, a battle to support a cause they might not necessarily agree with in the first place is happening on two different fronts. On one front, they’ve had to set aside their centralizing tendencies and think about a province in South Punjab – given the straight-jacket constraints applied by the PPP, and on the other front, popularity of the idea for a Hazara province means they have to show flexibility to retain their electoral capital in those districts.

One way or another, this talk about making new provinces is fairly unprecedented, and, very symbolic of the way PPP has shaped federation discourse in its now three and a half year long term. In legal terms, the constitutional guidelines for making a new province are covered in Article 1 (3), ‘Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament)] may by law admit into the Federation new States or areas on such terms and conditions as it thinks fit’ and in Article 236 (4), ‘A Bill to amend the Constitution which would have the effect of altering the limits of a Province shall not be presented to the President for assent unless it has been passed by the Provincial Assembly of that Province by the votes of not less than two-thirds of its total membership,’

That’s the de jure aspect of this issue. The de facto aspect is, as always, a lot more complicated.

A History of Administrative Cartography in Punjab (and Khyber Pakhutnkhwa)

A few days ago, in response to Javed Hashmi’s advice for dividing Punjab into several provinces, Shahid shared a Facebook page calling for the establishment of a Potohar province. The page administrators, in a bid to strengthen their cause on the cyber platform, state, ‘potohar pakistan banne se pehle se alag sooba ha is liay potohar ko alag kia jay’ (Potohar was a province before the creation of Pakistan, hence it should be separated now as well).

This is what we call in bazaari language, unadulterated bullshit. There is no record of a Potohar province existing over the last 200 years, and I’m willing to bet a fair amount of money on the fact that Potohar as a distinct cartographic entity has not existed till well before the advent of the Mughals. The reversion to history, an oft-used instrument, for the explicit purpose of strengthening a cause is symptomatic of provincialism/separatism across the world. Balochistan, or the Kalat confederacy at least, uses the same instrument to prove its existence as an independent entity. People have used this argument for the creation of Pakistan, and for the Balkanization of Yugoslavia. It seems, and increasingly so, that history is the ultimate arbiter in the fight to determine geographical boundaries.

Amusing really, considering that the concept of holding imaginary lines sacred is not that old itself.

The problem with this approach is that you really don’t know where to put a road block and call it 0:00, i.e., the moment from where history starts. In the context of Punjab for example, modern cartography is normally traced back to the hey-dey of the Mughal empire, when the area where we now live in was nothing more than barren, nomadic wasteland. Another perspective is to take the Bengal landing, and the Battle of Plassey as a concrete historical marker in terms of mapping modern India. Whatever view one picks, the fact is that the provincialist argues for a province, which would enable a higher standard of living within the framework of a modern administrative structure. Under these explicit terms, a history of Indian provinces, especially Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, can only go as back as the 19th century.

At the height of Sikh expanse, both Peshawar and Multan were part of the same geographical entity, colloquially known as the ‘State of Lahore’ (minus the princely state of Bahawalpur). After British annexation, the Anglo-Afghan Wars, and the demarcation of the Durand Line, areas now part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) were ruled till 1901 by the then Lt. Governor of Punjab, after which KPK was formally commissioned as a Chief Commissioner’s province. At that time, most of the KPK landmass was categorized as either Federally Administered Tribal Areas, or as a Provincially Administered one, with different legal and administrative structures. The KPK province consisted of only 5 settled districts: Peshawar, Bannu, Kohat, Dera Ismail Khan, and Hazara.

Hazara was the name given to the district bordering Rawalpindi, and at that time, was the only district of KPK to fall east of the Indus river. Prior to 1901, Hazara district was part of Rawalpindi division, and all three major towns (or tehsils), Haripur, Manshera, and Abbottabad were, for all intents and purposes, part of Punjab. While proponents of the Hazara province sometimes exaggerate their uniqueness, and their claim for autonomy, (given how the British classified their language as a dialect of ‘West Punjabi’), there is an administrative precedent of Hazara having its own identity, either as a district from 1901 to 1970, and as Hazara Division, consisting of Abbottabad, Manshera, Haripur, Kohistan, and most recently, Battagram, from 1970 to 2001.

On the other hand, South Punjab, or Seraikistan, has never existed as an administrative structure under the British or in modern day Pakistan. Multan, the largest city in the south, was the headquarter of a Mughal-era ‘subah’, i.e. a revenue region that ‘covered much of South-West Punjab, and even parts of Sindh’, till its annexation, first by Pashtun invaders, and then by Ranjit Singh. The language itself was recognized by the British as a dialect of Punjabi, traced on a spectrum moving from the North of the province to its South West regions. Moreover, since Bahawalpur was a princely state, consisting of Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalnagar as well, South Punjab in the British imagination was best captured by the Multan division, which was the 5th and least populated division of the province.

After independence, Bahawalpur retained its status as a princely state/pseudo-province, with its own representation in the constituent assembly. It remained so till the abolishment of princely states and enforcement of the One Unit scheme, and subsequently, was reborn as a division in 1971.

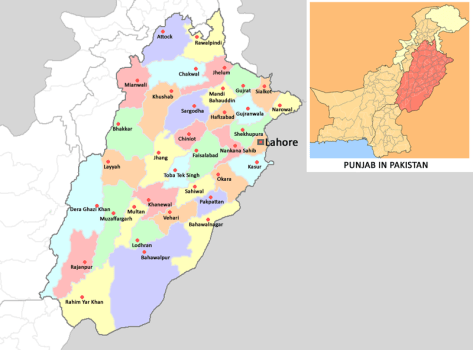

The very fact that there is no clear cut understanding of where a potential South Punjab province would start, and where it might end, causes further complications. The British classification of Multan division is problematic because at that time the districts that reported to Multan were Multan, DG Khan, Muzzaffargarh, Mianwali, and, weirdly enough, Jhang. Given that the entire population of Punjab was 20 million at that time, most of these districts were later split into two or more as the population increased after independence. Excluding Jhang, because locals there classify their dialect as Jhangochi and not Seraiki, the modern incarnation of a British South Punjab, with some manner of ethno-linguistic homogeneity, would consist of:

Multan, Khanewal, Lodhran, Vehari, Rajanpur, DG Khan, Layyah, Muzaffargarh, and Mianwali. If the Bahawalpur districts are included, then the list would expand to include Bahawalpur, Bahawalnagar, and Rahim Yar Khan as well. For all intents and purposes, this is nothing more than a collection of districts with Seraiki speakers that happen to be in Punjab. Hypothetically, if there was a move to create a Seraikistan from scratch, it would also have to include most parts of Sindh, especially places such as Sangarh, Nawabshah etc, parts of Balochistan, such as Jafarabad, Nasirabad, and parts of KPK, such as DI Khan, and Bannu (please to note that Mianwali was part of Bannu district till 1901).

This is a potential map of South Punjab if Bahawalpur division is included, and Mianwali + Bhakkar are not:

As one can see, map A appears to be a realistic division of the Province along straight forward North-South lines. Interestingly enough, the government, in the last 2 decades, has taken Layyah away from Mianwali, and added it as a district of DG Khan division. On the other hand, Bhakkar and Mianwali were made part of Sargodha divsion, which in one sense adds a veneer of ‘northern-ess’ to those two districts.

The Development Aspect of South Punjab

It’s hard to dig up solid North-South comparisons in terms of development numbers, but there are a few things that need to be mentioned here:

Total number of divisions and districts in South Punjab: 3 Divisions (DGK, MUL, BWP), 11 Districts

Total number of divisions and districts in North Punjab: 6 (LHR, GJW, FBD, SGD, RWP, SWL), 25 Districts

Total population of South Punjab is: 24.4 million

Total population of North Punjab is: 52 million

Avg HDI score for South Punjab districts: 0.632 (8 out of 11 districts in South Punjab fall below the provincial average of 0.67)

Avg HDI score for North Punjab districts: 0.691

Largest urban center in South Punjab is Multan, while the next biggest city is Rahim Yar Khan with a population of around 400,000. Compare this to North Punjab which has Rawalpindi, Lahore, Gujranwala, Faisalabad, all with a population above 3 million. While there are no readily available statistics regarding economy and labor employment in the two regions, it’s fairly obvious that South Punjab has larger land holdings, a greater reliance on Agriculture and Agro-industry, and a proportionately much larger rural population (gleaned from district level economy figures). Even in terms of educational institutions, the disparity is far greater than the 1 to 2 ratio suggested by population numbers.

The Politics of a New Province

As stated earlier, the constitution makes it very clear that a new province would require the assembly of the existing province to pass a delimitation bill by consent of two-thirds of its members. Given the way parties are currently maneuvering, the PML-N suffering from a delayed response, are currently on the back-foot in terms of their stance on South Punjab. After repeatedly refusing to carve out a province on the basis of ethno-linguistic footing, the PML-N has been cornered into formulating a committee with the explicit aim to look at the potential to create new provinces. The plural term has been used deliberately by the PML-N, as it negotiates political space in Hazara as well. After losing in the NA-21, Manshera, by-election, partly as a result of not taking up the Hazara cause the PML-N has had to come up with a strategy, principally to avoid being tied down in Central and North Punjab come election time.

With PPP taking up first movers advantage, and successfully generating the perception that a) a new province is in the greater interest of the Seraiki population, and b) it is the only party serious about delivering this new province, the PML-N has had to play on the PPP’s turf. Now a very reasonable question that can be asked is that why was the party mostly blind in terms of recognizing the potential for political mileage in this situation?

Well there are a number of explanations, out of which the most plausible ones invoke party structure and party sociology. For starters, PML-N is an urban party. Yes, I know this is an oft-mentioned cliche, but there are numbers to back this up. A constituency-by-constituency reading of Faisalabad revealed that NA-75 to NA-81 are all rural seats (Samundari, Chak Jhumra, Tandlianwala, Jaranwala) and have zero PML-N MNAs. In Gujranwala, the two non PML-N seats, are also the most rural constituencies in the district. The reason why Gujranwala and Faisalabad act as good examples is because they’re important districts from central Punjab, often referred to as a PML-N stronghold. The complete inability to institutionalize a party in rural areas across Punjab has been a recurring problem for the PML-N – one which usually results in an over-reliance on local patrons and electables. The urban skew in the PML-N’s thinking is also a direct result of the incredibly urban nature of their party-high command, and their preference for retired bureaucrats and technocrats as policy-advisers.

Electoral politics aside, the PML-N’s policy paradigm has also always remained heavily urban-centric. Their entire politics runs on urban development, like infrastructure development projects, and commercial activity. Their legislative positions reflect this nature such as their opposition to the Reformed General Sales Tax. Even their outreach to the public usually stops with the urban lower middle class, with projects like the Yellow Cab scheme, the Sasti Roti scheme, Daanish Schools, and Aashiana Housing. On the other hand, the PPP, after shrugging off incessant media-criticism (some of it justified), has catered to its mostly rural electorate with things like the BISP, increased wheat support prices, distributing free farming implements, and providing cash transfers to flood-affected households, most of whom were in rural areas. The result has been that the PPP, at least apparently, seems to be in an okay-ish position, despite a terrible governance record.

Given the PML-N’s rural blindspot, it doesn’t know what to make of South Punjab in general. It’s development priorities have been skewed heavily towards Lahore and its surrounding regions, and its brand of urban politics is generally not suited for the agrarian Seraiki belt. South Punjab has a total of 43 national assembly seats, compared to North Punjab’s 100. (which makes sense in terms of the 1 to 2 population ratio), out of which PML-N has 8, PPP has 21, PML(F) has 1, PML-Q has 10, and 2 are with Independents. Out of the 8 PML-N seats, 4 seats are wholly urban constituencies in Multan, Layyah, and Bahawalpur. Given these figures, and the PPP’s ability to generate a PML-N = anti-Seraiki perception, the party would have to, at least rhetorically, pay homage to the idea of a new province to stay relevant whenever elections are held.

The discourse surrounding a new province, which one way or another, comes out looking like an ethno-linguistic question, has been skillfully shaped by the PPP. While it’s too soon to say whether their campaigning will turn into anything concrete, in policy and electoral terms, the fact that a centralized structure is being tested via devolution and delimitation into something more devolved is a major development. Personally, I think dividing Punjab into two or more parts is a sensible thing to do, given its size, politics, and national footprint, but it must be remembered that this is merely the first step towards creating devolved, and responsive state structures in the southern districts. The real work will come when and if this new province is finally brought into existence.

(HDI and population figures were taken from a UNDP report on district level development. Umair Javed is a student of South Asian political sociology and history. He tweets as @umairjav.)

Previously in Kafila:

- In Defence of Asif Ali Zardari: Abdullah Zaidi

- Militant Rationalities: Ali Usman Qasmi

- Reading Land and Reform in Pakistan

There’s a third angle I don’t think mentioned; that of restoring Bahawalpur’s status as a state.

LikeLike