Guest Post and Photograps by RAVINDER KAUR

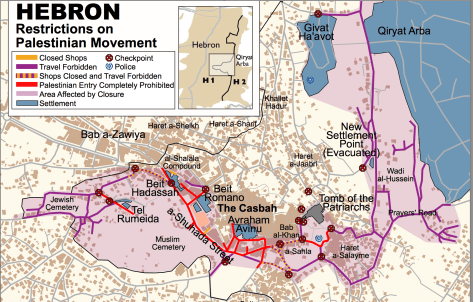

Map of Hebron, Courtesy ‘Breaking the Silence‘

On 12th June, 2014, the kidnapping of three Israeli teenagers near Hebron resulted a massive military search operation in the area. Since 30th June when their dead bodies were found north of Hebron, a Palestinian teenager has been abducted and killed in a revenge attack in East Jerusalem, and concerted air strikes have been launched on Gaza by the Israeli forces as punishment to Hamas who Israel holds responsible for the abduction and murder of the teenagers. In ten days of Israeli air strikes more than 216 have been killed in Gaza, and rocket firing by Hamas has claimed one life in Israel. A ground invasion began yesterday evening. Even as talks of a possible ceasefire, and resuming normal life, take shape, one might consider what ‘normality’ constitutes in a place like Hebron that has been at the center of the current conflict. It is in the normal, the routine that the spectacular violence takes shape.

An unexpected sight awaits the visitors who venture barely 50 meters beyond the Patriarch’s Tomb in Hebron. The main arterial street, Shuhada, running through the old Souk the city has long been famous for, is strangely empty. In fact, the entire Souk and the adjoining area remains enveloped in dead silence. If the streets wear a ghostly appearance, then it is because they have been empty since early 1990s. The ngo’s and political activists call this area the ‘ghost town’. But as dissident ex-soldiers turned peace activists with Breaking the Silence group now tell us, in the military speak of IDF the area has another name: the sterilized zone. Sterilization in bio-medical terms suggests processes of destruction and cleansing, of erasing, removing unwanted matter in an area. In the contemporary securitization discourse, sterilized areas are the protected zones from where the enemy threat, the danger, has been successfully removed. The choice of this expression to describe the removal of an entire civilian population is telling.

The sterilization process in Hebron began when a number of prohibitions and restrictions on the movement of Palestinians were imposed after the first and second Intifada by the Israeli authorities. These included restrictions on driving on certain roads, on walking on specific streets, and on both driving and walking on some streets in an effort to protect the growing presence of Israeli settlements in the area. Given the array of complex rules and practices, both legal and illegal, Hebron is considered by the peace activists as the microcosm of Israeli occupation. It is here, in the routine, mundane everyday life that one can witness the ways in which the military operation, the settlements, the occupation works. The hollowness of the logic of security is revealed here too. The city center was emptied either directly on military orders as a security measure or because of the restrictions placed on the movement of Palestinians had made commercial activity impossible. As a result, the bustling market area, a key trade center in the West Bank collapsed. In 2007, B’teselem (Peace Now), an Israeli peace organization, estimated that 1,014 Palestinian housing units and 1,829 commercial establishments now lie vacant in this area. The numbers have only grown since then. Three days after the kidnapping of three teenagers from the nearby settlement of Gush Etziyon, the handful of shops facing the Tomb were also shut down. By then 150 people from Hebron had been arrested by the Israeli authorities. And all entry checkpoints to Hebron, barring one leading from the nearby settlement of Qiryat Arba that was kept open for the settlers, were closed. The city was almost silent.

This is a map of Hebron showing streets that Palestinians are prohibited from walking and/driving on

Once the restrictions on movement were put in place, it became impossible for Palestinian shopkeepers and customers to access the area. In the old market near Shuhada that has remained closed since the 1990s, some shops were vacated due to direct military orders, others because they could no longer be accessed by the owners.

Some houses are still inhabited, but the Palestinian residents are not allowed to use the main door to enter/exit as they are prohibited from stepping on the street. They often use the backdoor if they have one, or take circuitous, difficult routes over roofs to reach the neighboring houses that have a backdoor. The windows above the empty shops have metal caged bars to avoid attacks and abuses from the Israeli settlers.

The empty streets continue to be patrolled by soldiers in order to enforce prohibitions. The young Palestinian boy seen cycling on the street in the picture above seemed to know the boundaries of the sterilized zone. He and his friends (not seen here) always turned back before reaching the soldiers post.

Garbage piled high around a couple of homes that are still inhabited around Shuhada does not get cleared for days. The practice of throwing trash by settlers who have occupied empty homes is a popular measure to harass the remaining Palestinian residents.

These three perpendicular slabs of concrete constitute a ‘Min-Wall’ blocking access to the Souk (Bazaar). It is a miniature version of the pre-fab concrete-slab design of the separation wall that Israel has built in the West Bank.

Here (above) is an Israeli settler walking past the military post on Shuhada, an act that is illegal for Palestinians. The homes that had been emptied as a security measure in some instances have been taken over by Israeli settlers.

Some empty commercial establishments are now being reopened by the settlers who have taken over.

A range of services provided for the settlers by the Israeli authorities including kindergartens for small kids.

A soldier on duty is seen here, chatting animatedly with a young settler. The testimonies of ex-soldiers reveal that such scenes are not extraordinary as there is often a degree of intimacy between the soldiers and the settlers.

This is Avner Gvaryahu. He was my companion in this journey. He cleverly found his way through the settement into Hebron. Avner, is an Ex-Soldier in the Israeli Army. Like a growing number of former soldiers, he is now an activist with ‘Breaking the Silence’ a group of mainly ex-IDF (Israeli Army) soldiers who organize in support of the human rights of Palestinians in the occupied territories and in Israel and against the Israeli state’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

Here is a military barrier dividing a street in the neighborhood. The logic of security becomes hollow here given that partition barriers can easily be crossed. The critics have often pointed out that the separation infrastructure in the name of security is more a measure to mark territory.

This (above) is a pictorial depiction of the residents of Hebron painted by Israeli settlers on an abandoned door. The second picture in top row from left represents Palestinian as a suicide bomber with explosives tied around the waist.

This is a view of the nearby settlement Qiryat Arba. Hebron can be approached through the connecting gates, through the settlements that are always kept open for the Israeli settlers .

Even when the city is sealed for the Palestinian residents by the military.

Ravinder Kaur is the author of Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi, Oxford University Press.