Guest post by KARTIK MAINI

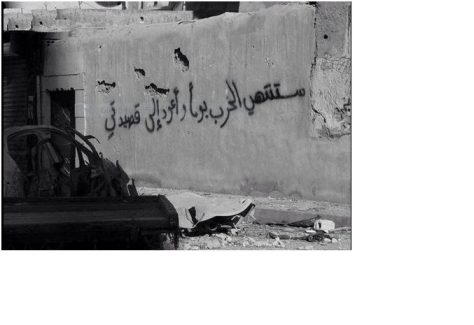

One day, the war will end, and I will return to my poetry

One day, the war will end, and I will return to my poetry

Contemporary India loves its army. For a civilisation that defines itself as intrinsically nonviolent, we do also love our wars.

On 23 July, 2017, Vice Chancellor Jagadesh Kumar, students of the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and members of Veterans India – a collective of ex-servicemen, gathered to commemorate the Kargil Vijay Diwas. The impulse of the commemoration is two-fold – it is a celebration of the Indian army’s reclamation of Kargil from Pakistani encroachment, as also an occasion to mourn the war’s martyrs who sacrificed their lives in service of the nation. For a university, commemoration should involve a quiet moment of reflection on the enormous human costs of war.

Mourning the martyrs of the Kargil War should compel us to acknowledge that wars are only too easy to begin and appallingly difficult to end. For the martyrs the collective claimed to be representing, the war never ended. That, in itself, is a humbling political reality, especially for those in the gathering and the recesses of social media who consider war a tantalizing prospect, a jingoistic expression of the might of the nation. For those, in other words, who forget that the nation is its people. The Kargil Vijay Diwas honours our freedoms and the dauntless men who died fighting for them. Freedoms we often take for granted without recognising their historical burden, and freedoms, dare I say, that can never be a privilege to be learned as fear.

But the gathering at the JNU Convention Centre was far from reflective.

In his address, Vice Chancellor Jagadesh Kumar said,

I request General V.K. Singh to help us procure an army tank so that we may place it at a prominent place in JNU. The presence of the tank will remind thousands of students about the great sacrifices and valour of the Indian army.”

The call for an installation of nationalism in JNU, like the army tank, is not unprecedented. Similar, if not relatively rabid, comments were made in the aftermath of the contentious protest on 9 February, 2016 addressing Kashmir and the hanging of Afzal Guru. Adding to the rhetoric, General G.D. Bakshi remarked,

While the stronghold of JNU is being captured, the other qilas of Jadavpur University and Hyderabad Central University remain to be captured as well.

Perhaps the most instructive in this bedlam of voices was B.K. Mishra’s, head of Veterans India, who declared,

We will create a situation where people will love the nation. And if they don’t, we will force them to love it.

The three comments, presumably unrelated, betray a monolithic imagination of the nation, and in that, OF the university. Before this imagination is addressed, General Bakshi’s characterisation of the JNU, Jadavpur University, and the Hyderabad Central University as unwieldy qilas to be captured begs the question – what is to be a university?

To phrase it as such bestows on the university a certain responsibility ‘to be.’ As events since the unforeseen rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party make clear, the university can have many meanings and is rather elusive. In all essentials, however, the university is an organism of ideas, necessarily in the plural. Unlike the nation or Hindutva, the university does not fear a plurality of ideas – it is, in fact, the responsibility of the university to ensure this plurality. No idea at the university is to be assumed or taken as pre-given; if there is no questioning, there is no education. Within and beyond its vast realm of ideas, the university attempts to reflect on dilemmas of the present, past, and the future. Sometimes, there are answers. Often, the questions answer and the answers question.

Such a conception of the university would be most unfamiliar to us – that ideas can exist for the sake of ideas is a radical reflection long forgotten. Since India let down its economic borders at the turn of the twentieth century, it is a lesson we have never revisited. The university, hitherto inward-looking, has had to look at the ‘industry,’ making an enterprise of education, workers of teachers, and consumers of students. The anxiety to propel the student towards pursuits more productive than ideas urges politicians and the taxpaying populace to remind the JNU and its students to ‘study’ and ‘do politics later.’ It threatens power, or those in power, that there be a place where ideas can move with a flexibility of imagination, where nothing is to be accepted, not even the nation, until it is questioned. The mere existence of the university is a persistent menace to those whose work is the impression of an imagination in the minds of the masses. To Hindutva, there is tremendous fear in both the plurality of ideas and people – it augurs well that universities have become elite enclaves, sustaining class apartheid in education. But JNU, with its avenues of opportunity for the most deprived, unsettles this peace. If Hindutva desires the primacy of people who live, look, worship, and love a certain way, students of the JNU refuse to share the imagination. No university can.

The installation of the army tank, as Vice Chancellor Jagadesh Kumar has requested, “would remind thousands of students about the great sacrifices and valour of the Indian army.” How does, one wonders, an armoured vehicle designed for manoeuvrability in warfare reflect great sacrifice and greatest valour? Would not a memorial serve such a purpose, memorialising “the great sacrifices and valour of the Indian army” in perpetuity? The purpose of the memorial is to remember war. Remembering the depredations of war makes glamourizing it difficult. The purpose of the imposing army tank, paraded annually to celebrate the potency of the republic, is to command obedience.

When General Bakshi refers to the university as a qila, he betrays that the objective is not to teach virtue, but conquer. The intimidating, fearful presence of the tank is the template of the university in India. It commands unrelenting acceptance of a monolithic idea of the nation, something that universities across the country have refused to, and in that, a monolithic vision of the university. Any sincere opposition to this would have to take critical recourse to the realm of ideas, and if it is to do that, to the university.

When all the wars are over, wrote Ruskin Bond, a butterfly would still be beautiful. The words on the wall with which we began, let us remember were:

One day, the war will end, and I will return to my poetry

The university is this butterfly, this unwritten, unfinished poetry that runs against seemingly invincible attempts to muzzle.

How can an army tank, let alone an installation, vanquish the passion of the university?

Hindutva brigade nourished on ‘ war ‘ epics must remember the famous quote every time they praise war ..

” There was never a good war nor a bad peace ” …

They cannot establish peace through warmongering rhetoric ..

LikeLike