This guest post by ANIRUDDHA DUTTA continues a theme raised on Kafila by Rahul Rao

Late last year, the UK and US governments made announcements supporting the global propagation of LGBT (lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender) rights as human rights, suggesting that the future disbursal of aid might be made conditional on how LGBT-friendly recipient countries are perceived to be. The potential imposition of ‘gay conditionality’ on aid has been rightly critiqued for imposing a US/European model of sexual progress on ‘developing’ countries, which may justify covert geopolitical agendas and fail to actually benefit marginalized groups. But whatever form such conditionalities may take in the future, a more implicit and routine form of aid conditionality has been already at work, relatively unnoticed, for several years now – the presumption of distinct and enumerable minorities corresponding to categories like homosexual or transgender as target groups for aid in socio-cultural contexts where gender/sexual variance may not be reducible to such clear-cut categories or identities. Increasingly, community-based organizations (CBOs) working to gain gender/sexual rights or freedoms need to define themselves in accordance with dominant frameworks of gender-sexual identity to get funding both from foreign donors and the Indian state, creating identity-based divisions among CBOs and presenting existential challenges to communities that do not exactly fit these categories.

Through the past decade, India has seen a booming growth of NGOs working for ‘sexual minorities’, especially in the sector of HIV-prevention, funded both through the Indian state and foreign donors such as the UK’s DFID (Department for International Development). While this has facilitated the “coming out” of queerness in the media, civil society, and state policy, it has also created a normative script for identity and recognition through implicit and explicit aid conditionalities through which ‘sexual minorities’ get funded. Even as the Indian government has hesitated to support the decriminalization of same-sex relations, the Indian health ministry is actively involved in funding health-based interventions for gender-sexually variant people – especially for those born male (though not necessarily identifying as such), seen as being at high risk for HIV-AIDS. (Queer women and female-born transpersons are left out of HIV-AIDS funding, supposedly not at high risk – a problem that needs separate exposition elsewhere). This article will focus on a spectrum of male-born gender/sexually variant persons and communities for whom the health ministry and the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) mediate foreign aid for HIV-AIDS prevention, influencing not only whether their sexual/gender variance is to be decriminalized and politically recognized, but also how it is to be recognized.

A binary framework

What forms of identification are being legitimized through this process, and what forms of identity/behavior are not? While previously all funding for ‘sexual minorities’, including for ‘third gender’ hijras, was disbursed through interventions for ‘MSM’ (men-who-have-sex-with-men or males-who-have-sex-with-males), now the health ministry and NACO have started separating sexual health interventions into MSM and TG (male-to-female transgender) categories, as announced in the NGO world and mentioned in at least one media report. Herein lies a story, for both MSM and TG categories, in the way they are currently conceptualized, carry normative ideas of gender/sexual identity, ultimately based on a binary man-woman divide. The MSM-TG division may not only exclude people who do not ‘fit’ these labels, but also splinter existing marginalized communities of gender/sexually variant people into narrow identitarian groups. This particularly affects communities and community-based organizations in non-metropolitan and rural areas, which are more dependent on such funding than metropolitan middle class LGBT groups.

In the new funding regime that is increasingly getting standardized, the two broad legitimized categories for male-born people are MSM/gay/homosexual (men desiring men) on one side and male-to-female transgender on the other, where TG is commonly glossed as those identifying as or desiring to be women. Hijras are either seen as a subset of TG or a closely linked group (see this 2008 UNDP report for emerging MSM-TG divisions and this 2009 report for emerging definitions of TG). These reports mark a shift from common perceptions where homosexuality and gender variance have often been seen as closely related, if not the same thing – witness the widespread stereotyped equation between gayness and effeminacy in the media. This association was implicit in state policy as well; one of the primary sub-categories of MSM in India under the third phase of the National AIDS Control Program (NACP-III, 2007-12) was the ‘kothi’, a complex and ambiguously-bordered category used in lower class community networks and hijra groups, which NACO defines as “males who show varying degrees of femininity” (see document on high-risk groups available here). However, increasingly, the government, its funders and larger NGOs have become very interested in distinguishing exactly who among gender-sexually variant people are really ‘transgender’ (commonly defined as ‘female/women’ in a male body), and who are really ‘men having sex with men’ (increasingly narrowing MSM from its former inclusion of all biological maleness into a gendered category for ‘men’). While the MSM category focused mainly on sexual behavior, ‘transgender’ allows for gender identity and gender-based discrimination to be factored into funding policy: which is certainly a positive development. However, if MSM and TG are understood in simplistic terms as mutually exclusive and separable identities/communities (rather than flexibly overlapping terms), it creates a restrictive binary cartography or framework for identification in the same old societal mould that is being contested, involving the question of who is really a ‘man’ (albeit a same-sex desiring one), and who is really a (trans) ‘woman’.

Such an MSM-TG division can have wide-ranging and divisive effects on organizations and communities that in practice have been flexibly overlapping. It threatens to split marginalized communities and networks into separately funded, competing groups – communities where, as a PhD student/researcher, I have observed a complex spectrum of ‘masculine’ to ‘feminine’ identified people. This could include people who identify as (trans)women or hijra, people who identify as feminine males (using terms like kothi, dhurani, gay), people who switch between identities and gender presentations, people who don’t identify as anything at all but still participate in such networks/communities, people who identify only during specific occupations such as dancing at festivals or sex work, and so on. However, to fall into the ambit of government-funded AIDS interventions now, one has to be classified as either MSM or TG. Moreover, it is sometimes stipulated that a single community-based organization (CBO) cannot have both MSM and TG people, as seen below in an empanelment call for CBOs by the State AIDS Control Society in Bengal in 2011, which asked for TG-exclusive CBOs:

Fig.1 WBSAPCS Empanelment Call (excerpts)

Like the above call for CBO empanelment, several national coalitions of NGOs too increasingly ask member organizations to identify as working with either MSM or TG communities, or at least to sub-divide their population into precisely enumerated ‘MSM’ and ‘TG’ sub-groups. To many small non-metropolitan CBOs, this has posed problems. Working with a complex community spectrum ranging from ‘feminine’ males to transwomen, they have to now classify themselves as either MSM or TG to the state, and/or have to sub-divide their population into this binary framework for other foreign-funded projects such as the Global Fund-aided Project Pehchan. This causes confusion regarding the ‘correct’ term to identify with, and anxiety about the potential to miss out on funding if the representation is not consistent. In some cases, the process of arriving at a ‘correct’ and acceptable representation for the state has caused delays in achieving funding, even as people died for lack of HIV-AIDS related services in the area. For instance, Sangram, a CBO in mid-North Bengal, was not able to get HIV funding for several years between 2006 and 2011, despite an estimated nine AIDS-related deaths in their district during the period. First told that they did not have enough sexual minority population in the area, there was further delay over whether they were to be empanelled as a TG organization or as an MSM one. CBO representatives even wondered whether they were expected to put on particular attire or present themselves in a particular way (either more or less ‘feminine’) in order to be perceived as ‘authentically’ TG or MSM by representatives of the West Bengal State AIDS Prevention and Control Society. Finally, after being empanelled during the TG empanelment process, they were given an MSM project. Meanwhile, at least two people with AIDS died in the area.

These hurdles of representation further worsen the bureaucratic hassles with funding that routinely hamper state-funded MSM/TG intervention projects – including long gaps between funding cycles, months-long delays in getting staff salaries, and corruption or misappropriation of funds at higher administrative levels of state AIDS control bodies (as exposed by this report from West Bengal). Just as importantly, the imposition of identity stipulations also adds to a hierarchical, exploitative system where community-level workers (especially peer educators, the foot soldiers of HIV-AIDS prevention) are paid less than minimum wage salaries (usually ‘honoraria’ of less than Rs. 2000 per month), as this report from Karnataka attests. Meanwhile, their ‘partners’ in metropolitan NGOs and funding organizations enjoy far more generous salaries and commensurate social recognition, further exacerbating class and experiential divides.

The arrival of transgender

This is not to deny the importance of the entry of transgender into policy, which was a necessary development. There is not enough space here to offer a detailed history of how TG became a funded category. But briefly, one way in which TG entered state and funders’ policy was due to activists’ demands to revise the funding regime to address gender issues more effectively – as shown during national and regional consultations among NGO leaders conducted by UNDP (the United Nations Development Programme) in 2008 and 2009. The third phase of the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP-III) designed targeted interventions for ‘MSM’, and marked MSM/TG as a singular entity. The subsumption of all groups under the epidemiological and behavioral label MSM neglected gender-based discrimination and violence, and marked sexual health as the overarching issue. Thus all male-born ‘sexual minorities’ were reductively seen as biological males (though not necessarily ‘men’), and interventions primarily addressed the risks of unprotected male-male sexual behavior. Quite justifiably, activists demanded that interventions should recognize those not identifying as males, and criticized MSM interventions for failing to address gender issues and discrimination. TG emerged as the umbrella term to accommodate gender variance, and newer NGO networks such as the Association of Transgender/Hijra in Bengal sought to explicitly deal with gender discrimination: again, a laudable development. This was parallel to the political demand to add ‘other’ as an option in the census and other government documentation, opening up the parameters of official identity beyond ‘male’ and ‘female’ – also an urgent and necessary demand.

However, rather than the reform and expansion of existing MSM interventions to better accommodate the gender variance of their target communities and address gender discrimination, TG soon became conceptualized as a separate identity and a competing funded group. This separation creates a new problem where the recognition of gender variance is effectively reduced to the sex-gender binary of male/female (homosexual males vs. transwomen). Indeed, ‘gender’ (transgender) and ‘sexuality’ (homosexuality) themselves become conceptualized separately, with gender variance becoming primarily the province of TG identity/activism (as David Valentine has argued about the gay-transgender divide in the US context). This does not address gender variance within existing MSM interventions – making MSM itself into a narrowly gendered term – and confines gender-based anti-discrimination work to TG projects/interventions. Moreover, once TG is opposed to MSM as a separate identity, rather than seen as an overlapping category that can be strategically used to address gender-related issues affecting a variety of persons, its scope is reduced to cover only a very narrow script of transgender identity. As I describe below, for male-born people, TG often gets circumscribed as per conformity with cultural femininity and may establish what Ricki Wilchins has called a ‘hierarchy of legitimacy’ where some are more ‘authentically’ TG than others. And of course, there is no mention of caste/class issues in both the older and newer funding regimes, even though MSM-TG communities who rely on such funding are often lower-middle to lower class, which is crucial to understanding and mobilizing from their social situation.

The dangers of unitary identification

Although the MSM/TG divide now exists on paper and within funding mechanisms, in practice attempts to produce a separate, clearly demarcated or unified transgender identity have run into problems and not resulted in any consensus. A news article in Bangalore claims that most TGs want to be identified as ‘female’ (and not ‘other’ or ‘transgender’) on official forms. But another Hyderabad-based report states that some TG-identified people complain about being forced to identify as ‘female’, and indeed want to identify as ‘other’. While in the first case an NGO activist claims that the ‘majority of TGs’ want to be women-identified, in the second case the local NGO is disappointed with those identifying as ‘female’, and politically favors that TGs should identify as ‘other’. Both the articles want to seek out a majority and a singular definition of TG – which risks marginalizing any ‘minority’ section that does not fit whatever the ‘right’ definition of ‘transgender’ is supposed to be in that particular NGO or community. The absurdity of the attempt is compounded by the fact that ‘transgender’ is a relatively new term even in English, and is obviously unfamiliar to a lot of lower or lower/middle class gender-sexually variant communities.

The dangers of basing official recognition or service provision on unitary identities is well demonstrated by the case of gender variant people who have encountered life-threatening problems due to having a combination of ‘male’ and ‘female’ listed on different forms – like the case of Bini, a hijra community member who couldn’t get easily admitted to hospitals in Kolkata because of having her sex listed differently in different forms (see this report in the Bengali media). Proposing ‘female’ or ‘other’ as a unitary identity for all ‘transgenders’ might not solve but actually compound this problem, given that many community members already have ‘female’ or ‘male’ on different forms, and unless they change all forms of identification to achieve one consistent identity, they might still be denied services on account of not being ‘properly’ transgender, unambiguously ‘other’. The demand for unitary and consistent identity, associated with middle class civil society and citizenship, might therefore be detrimental to communities lower down societal and organizational rungs. A better strategy seems to be to dissociate essential governmental and health services from sex-gender unless it is medically relevant, and/or to promote and permit flexible identification on a personal and case-by-case basis – which is challenging on a logistical level, yet perhaps crucial for long-term change.

Separation and overlap

On the level of organized HIV prevention and human rights work, an MSM-TG separation would make some sense where communities have formed along a masculinized gay identity (men-desiring-men), encouraged by the ubermasculine culture of gay porn which has little space for gender variance, or by the online culture of popular gay dating sites in India like www.planetromeo.com where injunctions like “no feminine guys please” are common on many personal profiles. Such communities, organized around a normatively masculine gay identity (partially in response or reaction to the effeminate gay stereotype), would indeed not have much space for gender variance and for femme, genderqueer, transgender, kothi, male-to-female transsexual (etc.) people. (For instance, certain well-known urban gay groups have been known to explicitly forbid cross-dressing in their events.) In such contexts, it is not my aim to advocate some anodyne homosexual-transgender unity (such as that signified by increasingly commoditized and banal images like the ‘rainbow’ LGBT flag), which would only serve to disguise the privilege and all-too-common transphobia of many masculine men-who-have-sex-with-men, whether gay-identified or not. Such a plastic ‘queer’ or LGBT unity might prevent rather than create the proverbial ‘safe space’ for those who really need it.

However, in most small towns and villages in Eastern India where I have worked over the last five years, networks and communities have not grown around such a rigid gay vs. transgender identity split, perhaps partly because it is not conventionally masculine-identified people who have been at the core of such spaces. Rather, there is a spectrum of gender variant persons spread between formal hijra gharanas (clans/groups) on one end, and loose cruising (sexual) networks on the other. In response to social stigma or abuse, such persons come together at cruising spots, parks, roadside haunts, and slowly with institutionalization, CBO offices. There are also occupational networks among people who do sex work (khajra), beg in trains (chhalla), or perform as launda dancers (cross-dressed dancing during festivals or marriages, primarily in UP/Bihar). There is a range of terms used to describe gender/sexually variant persons in these networks – kothi, dhurani, moga, launda, and of course, hijra – which describe a gender spectrum that cannot be neatly divided into the two sides of gay/homosexual men vs. male-to-female transgender. During NACP-III, NACO tried to designate these complex community networks under the MSM sub-group kothi, reductively defining kothi as ‘feminine’ males who take the penetrated position in sex, even while noting there are ‘varying degrees of femininity’ among them.

But even while the NACO and HIV interventions tried to stabilize this definition of the kothi, subcultural usages have remained more internally varied and flexible. Kothi is often locally translated and allied to terms like dhurani, meyeli purush (feminine male), and launda (in Bihar and UP). People might switch between labels or have ambivalent//plural identities across seasons or life stages – like many male-attired dhurani/kothis who cross-dress as laundas or transition to hijras – and moreover, there is no strict segregation between different kinds of people. There are some who cross-dress only occupationally, and talk of themselves as ‘effeminate males’, while others might see themselves as women all through, using metaphors like women-in-male-body – all within the same community without a strict spatial demarcation separating the (‘feminine’) males from the (trans) women. Metaphors like being a ‘woman inside’ which designate fixed identities co-exist with behavior-based classifications like ‘pon’ – tonnapon (masculine-behaved), niharinipon (feminine-behaved) – which permit transitions. This is not queer utopia – much of the fluidity is prompted by survival and occupational needs, and there might be tensions between those who are more fluid (e.g. laundas, sex workers) and those who have a more fixed identity (e.g. senior hijra gurus). However, there are also many friendships and kinships (e.g. sisterhood) among different people, facilitating identity switches and overlaps. (To an extent, this is true even in metropolitan communities where the aforementioned gay-TG divide is clearer). But instead of encouraging friendships and already existent kinship structures, the MSM-TG separation tends to divide community networks and build upon tensions.

Ghettoization and transphobia

Just as the emerging gay/TG divide in urban communities, stricter than their previous loose overlap, discourages boundary-crossings and perpetuates femme-phobia and transphobia, the identity politics around MSM-TG separation, linked to aid conditionality, might have similar effects in non-metropolitan communities. For instance, in West Bengal there have been intra-community allegations about cross-dressers not being encouraged in some MSM CBOs. Conversely, as I observed in emerging TG interventions/projects, there may be pressures to fit into a normative idea of being TG in order to access organizational spaces and services. At a new TG intervention near Kolkata, I saw that too ‘MSM’ behavior was not encouraged, since it must look like a TG CBO (i.e. participants should look as much like women as possible). Derided by a peer for being actually MSM, a kothi who was not really TG, one young community member said s/he would go in for laser facial hair removal, which is probably not something that s/he could easily afford. Thus, evolving ideas of proper TG-ness based on ideals of femininity has potentially adverse mental health impacts on those who do not fit, just as gayness increasingly valorizes a normative masculinity with exclusive effects. Can chhallawali kothis (cross-dressed train beggars outside hijra gharanas) or laundas who often switch between public gender roles pass as ‘properly’ TG or ‘properly’ MSM? TG loses its radical potential for addressing gender variance among male-born persons once it is opposed to ‘MSM’ and aligned with some normative idea of being feminine, which simply cannot be afforded by many poorer community members. Moreover, instead of TG empowerment, such separation might result in a ghettoization of TG issues, such that MSM interventions could refuse to deal with the needs of gender variant people in their local community, which more often than not would have a gender spectrum including TG-identified people and hijras. This defeats the purpose of transgender activism by actually further preventing services for gender variant people, and by making CBOs accountable only to narrowly defined identities rather than the complex communities from which they have arisen. This is also dangerous as not all areas have both MSM and TG interventions. For example, a recent case concerns Sujata (name changed), an hijra living with HIV who is being looked after by a TG organization after being disowned by her hijra gharana, and thus can no longer move out of the TG organization’s area for occupational needs or demand services of MSM organizations elsewhere. Such divisions along gender lines also cancel potential class/caste solidarity among the spectrum of differently-gendered people.

Since many non-metropolitan communities did not form according to a gendered either/or binary between gay men/MSM and TGs, many CBOs are unsure about how to fit into this new identity politics. Often the MSM/TG division is locally understood as one between different kinds of kothis or dhuranis, rather than separate identities per se. Attempts to categorize these terms into the MSM-TG cartography have resulted in inevitable ironies – kothi is mapped as TG by a 2009 UNDP-funded report, but as MSM in interventions by NACO and Project Pehchan. While policy documents do not acknowledge this overlap explicitly, it exposes the absurdity of the assumption that one has to be either MSM or TG, or that MSM and TG can be neatly separated and demarcated. As one kothi-identified person remarked to me, “kothis not only get fucked but fuck too, so it is a controversial term”, gesturing at the crossover of feminized receptive roles and more ‘masculine’ penetrative ones within these communities. A narrow sense of TG thus might perform a restrictive representation of gender variant people that fails to address the complexity and internal variety of such communities.

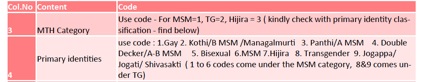

Fig.2 Mapping ‘primary identities’ like kothi into the MSM-TG-hijra cartography (Operational toolkit for interventions under Project Pehchan)

To conclude, transgender is a strategically important category that directs HIV-AIDS funding for male-born gender variant people to political organizing, and corrects the narrowly epidemiological focus of MSM on sexual behavior – but only if it is kept open as a strategic umbrella term and not reduced to a bounded identity mutually exclusive with MSM. Overcoming such aid conditionality would necessitate solidarities across gay-kothi–launda–dhurani–moga-TG-hijra-etc. categories, including and beyond identifications such as ‘woman-in-male-body’ or ‘man-desiring-man’: flexible friendships and/or sisterhood against patriarchy open to both more ‘masculine’ folks who are part of gender variant networks on one hand, and hijras and transsexuals on the other.

Aniruddha Dutta is a PhD candidate in Feminist Studies and Development Studies at the University of Minnesota.

Very well written.

Just that I don’t see a solution to this unless there’s an optimum amount of funding for the entire cause. Inadequate funding will always see a greater amount of in-group factioning in any case. That, in addition to the other reasons due to which there’s in-group factioning. Also, of course, optimal funding isn’t SUFFICIENT to guarantee diversification of aid and health-care but it surely is necessary.

That said, I don’t see why any group around the planet would bother to fund LGBT issues in India. In fact, I don’t even see why the Indian government would bother to grant appropriate funds to issue unless it’s an issue concerning the HIV-epidemic because HIV isn’t going to remain confined to a certain segment of the population ONLY. The government isn’t going to bother with TG discrimination and sex-change operations unless that would be a pre-requisite to reach out to them and even then I don’t think the funding is going to be enough.

What are the ways out? Like Udayan mentioned in the facebook forum, the only possible ways I see out are for groups to grow more and more self-reliant. In the sense that they establish their own industry, find markets where they can sell their goods and products or services (not talking about sex here) and earn enough to let THAT go into their well-being. Yet again, this is all very hypothetical and probably even impractical, considering that would require an entire shift of lifestyle…

LikeLike

Tanmay, I quite agree with you that competition over limited funding/resources is a major cause of factionism, and that relying on external funding (whether from the Indian state or foreign donors or – as it usually happens – the latter via the former) is ultimately unsustainable. Self-reliance and economic independence are also sine qua non for empowerment in the long term, both in the sense of gender/sexual freedoms and sexual health. However, as you point out, that is easier recommended than achieved. What I would argue in that context is that one cannot (or shouldn’t) simply advocate lower class self-reliance (pulling oneself up by the bootstraps etc.) without taking into account how the aforementioned communities (whatever be their names or [non]identities) are already contributors to important social and economic sectors, most prominently of course the HIV-AIDS industry but also rural entertainment (e.g. Launda dancing) and indeed sex work too, and one can’t simply ask ‘them’ to become ‘self-reliant’ without also advocating greater justice and equity within those sectors and rectifying the exploitative structures within state-funded HIV-prevention, sex work, entertainment, etc. that ultimately prevent self-reliance and economic independence. This is not to disagree with your underlying suggestion that becoming independent producers/contributors to local economies would be crucial to correct funding-related dependencies, but rather to add that economic empowerment and social justice might be fundamentally interrelated.

Also, a related point is that in many cases, ‘they’ are already compelled to be highly self-reliant, which however doesn’t translate to being economically empowered – e.g. presently one of the largest CBO networks in eastern India is undergoing a months-long gap in funding from the state AIDS prevention/control body and while leaders/activists are attempting to sort it out, ‘grassroots’ community members who were employed as its staff have been fending for themselves through various kinds of low-paid occupations (domestic labor, odd jobs, etc. – not just sex work!!), even as their rightful dues/salaries have been withheld for six or more months. This also suggests how the problems of ‘these’ communities are integrally connected to larger issues facing the rural and urban poor of South Asia, rather than being uniquely ‘LGBT’ (and one might argue that they are more crucially a part of urban/rural lower classes, rather than some mythical ‘LGBT’ community unified across class). Thus, economic self-empowerment for the gender/sexually marginalised would need to be linked to the broader context of poverty and class/caste in India than being just seen through an LGBT or gender/sexuality lens, and as long as broader patterns of poverty and class/caste disempowerment do not change through broader struggles for economic empowerment and social justice, it would be unreasonable to expect that ‘LGBT’ groups/communities/networks would suddenly be able to become self-reliant and economically independent even as their non-LGBT family members, friends, clients and neighbors are caught up in the same old cycles of poverty and exploitation.

LikeLike

Tanmay, I agree with you that competition over limited funding/resources is a major cause of factionism, and that relying on external funding (whether from the Indian state or foreign donors or – as it usually happens – the latter via the former) is ultimately unsustainable. Self-reliance and economic independence are also sine qua non for empowerment in the long term, both in the sense of gender/sexual freedoms and sexual health. However, as you point out, that is easier recommended than achieved. What I would argue in that context is that one cannot (or shouldn’t) simply advocate lower class self-reliance (pulling oneself up by the bootstraps etc.) without taking into account how the aforementioned communities (whatever be their names or [non]identities) are already contributors to important social and economic sectors, most prominently of course the HIV-AIDS industry but also rural entertainment (e.g. Launda dancing) and indeed sex work too, and one can’t simply ask ‘them’ to become ‘self-reliant’ without also advocating greater justice and equity within those sectors and rectifying the exploitative structures within state-funded HIV-prevention, sex work, entertainment, etc. that ultimately prevent self-reliance and economic independence. This is not to disagree with your underlying suggestion that becoming independent producers/contributors to local economies would be crucial to correct funding-related dependencies, but rather to add that economic empowerment and social justice might be fundamentally interrelated.

Also, a related point is that in many cases, ‘they’ are already compelled to be highly self-reliant, which however doesn’t translate to being economically empowered – e.g. presently one of the largest CBO networks in eastern India is undergoing a months-long gap in funding from the state AIDS prevention/control body and while leaders/activists are attempting to sort it out, ‘grassroots’ community members who were employed as its staff have been fending for themselves through various kinds of low-paid occupations (domestic labor, odd jobs, etc. – not just sex work!!), even as their rightful dues/salaries have been withheld for six or more months. This also suggests how the problems of ‘these’ communities are integrally connected to larger issues facing the rural and urban poor of South Asia, rather than being uniquely ‘LGBT’ (and one might argue that they are more crucially a part of urban/rural lower classes, rather than some mythical ‘LGBT’ community unified across class). Thus, economic self-empowerment for the gender/sexually marginalised would need to be linked to the broader context of poverty and class/caste in India than being just seen through an LGBT or gender/sexuality lens, and as long as broader patterns of poverty and class/caste disempowerment do not change through broader struggles for economic empowerment and social justice, it would be unreasonable to expect that ‘LGBT’ groups/communities/networks would suddenly be able to become self-reliant and economically independent even as their non-LGBT family members, friends, clients and neighbors are caught up in the same old cycles of poverty and exploitation.

LikeLike

Great post. I’ve been hard-pressed to find critical reflection on the HIV/AIDS MSM/TG NGO apparatus in India (for lack of a less clunky term) and this clarified some very important issues for me. Would love to hear your thoughts on the following:

– Where does the role of the “panthi,” or the usually straight-identified “top” in MSM/TG romantic/sexual relations fit into the issues you discussed? You talked about the uber-masculine behaviors and desires of metropolitan gay communities fueled by online cruising and gay porn, but didn’t mention the desire frequently (but of course not exclusively) enunciated by MSM/TG people for an uber-masculine partner of their own — a sexual and romantic partner outside the “sisterhood” of MSM/TG communities. Are panthis receiving the medical attention they need from CBOs, and are they affected by the growing MSM/TG divide you identified? What sorts of political organizing within TG/MSM communities is necessitated, or negated, by panthis? What separates panthis from masculine gay men in the eyes of MSM/TG — is it about self-identification, or class?

– You mentioned briefly the salary disparities between the CBO foot soldiers and those working the upper ranks. My anecdotal observations are that these class disparities also correspond to differences in self-identification. IE, those making the most money are also the most likely to identify not as MSM/TG but as gay, or to more intensely blur the distinction between MSM/TG and gay. Would you agree?

– This might go beyond the scope of your post, but what about the general fact that lower-class communities of sexually marginalized people are, as a consequence of funding, almost always politically organized under the banner of HIV/AIDS? Does the the public health angle significantly limit the scope and potential for MSM/TG activism, or have there been creative enough work-arounds? Does the growing and externally imposed MSM/TG divide necessitate that we rethink the entire apparatus through which MSM/TG political and medical needs are addressed?

LikeLike

Thanks, Jordan; those are great questions. Shall attempt to answer as best I can:

1. Yes, the ‘panthi’ (or the ‘parikh’ in West Bengal, ‘giriya’ in North India, etc.) is a fascinating figure – as you indicate, he can be thought of (and/or self-identify) as ‘straight’ or bi, but rarely/never as ‘gay’. The panthi/parikh is a figure of desire, yes, but also an antagonist (the empowered masculine man) who can also be a threat. The exclusion from inner circles (the ‘sisterhood’) is partial, as the ‘sisterhood’ as I argued in the piece above is itself internally variegated and ambiguously-bordered, but the relative externalization of consistently-masculine men is perhaps necessitated by perceived/real power equations. The gay-identified man is perhaps more likely to be mapped as ‘dupli’/’double-decker’ etc. than panthi, but these cartographies are dynamic and variable; an elucidation would necessitate a much longer space. (Also, perhaps the ‘panthi’ is more necessarily masculine than necessarily ‘top’; again there’s not enough space here to really explore that question). I don’t think the position of the ‘panthi’, whoever he is and however he may (not) identify, is particularly affected for good or bad by potential MSM/TG splits because, as often noted, it is hardly a self-identity, a core organizing group or a core target group for HIV-intervention in the first place. They are likely to occur as peripheral figures across ‘MSM’ or ‘TG’ CBOs in the case of segregation rather than a group affected by the split. They are not really treated as a high-risk group under NACO, since risk in this paradigm equals penetration; their medical needs might be more likely treated by PLHIV groups once they already have HIV rather than being a core focus of MSM/TG interventions. This of course leaves out a whole area of ‘high risk behavior’, but tell NACO that. As for political organizing, again probably they’d be part of broader interest groups along class/caste lines rather than organize as a ‘sexual minority’.

2. The relation between class and self-identification is complex. There’s an article in ‘Because I have a voice’ by Alok Gupta which deals with gay-kothi as a class divide. However, I think increasingly ‘gay’ travels up and down and so does ‘kothi/dhurani/hijra’, though perhaps less than gay, and there could be all sorts of overlaps or clashes. But ‘gay’ is obviously a much more publicly- and media-recognized term than any of the ‘vernacular’ ones (except hijra but even that is often substituted by ‘eunuch’ or ‘transgender’), and has more prestige (Kira Hall’s 2005 essay ‘Intertextual Sexuality’ is also interesting in making this kind of an argument). LGBT discourse and identification of course functions within the social/cultural capital of English; thus upper middle and middle class identifications are far more likely to be publicly expressed in those terms; there might be other registers of speech where other terms are also used. As for blurring MSM/TG and gay distinctions, I think that can occur in more lower class contexts as well, though the precise dynamics vary from more upper/middle class circles. Again, there’s a whole diss chapter in there, which unfortunately can’t fit into the space of this comment!

3. The HIV-AIDS angle certainly does impose constraints on MSM/TG activism, including the terms MSM-TG themselves as discussed in the piece above, however, I think there are all sorts of creative compromises people make, too numerous to list here. Given the extreme inequities of caste/class reflected within the HIV-AIDS and development sectors, I am often prompted to think that the continued survival of communities and kinships necessitates a huge deal of creativity in itself! (For a hint re. the various kinds of ongoing crises, a lot of which do not come into media notice, see my comment to Tanmay above).

As for critical work on the HIV-MSM-TG apparatus, there are three essays available by Lawrence Cohen, Akshay Khanna and Paul Boyce, do check them out if you haven’t read those already.

LikeLike

First of all, thank you very much for writing this article. While I was a reading it, I was thinking, what would a fund-disbursing official do or how would she decide on funding, given the complexities that this article has described through a thoroughly nuanced analysis. So, I have put on a donor-hat here!

1. One issue that needs to be remembered is that the “development” agencies, in charge of funding may have (or perhaps can be assumed to have) a completely different kind of expertise than the researchers working on a specific topic. Both the researchers and the funding agency officials often seem to stick to their own points of view and of course both have in varying degrees several other institutional imperatives to think of. The problem I find with many of the researchers (not all) is that, while they acknowledge the contributions of funding in terms of opening up the spaces of negotiations and mobilization, many of them are not willing to acknowledge the complexities, divisions, power relations within the funding agencies themselves that may often necessitate creating some kind of a “standardized” format for grant disbursal. Taking account of the wide range of variations and the “spectrum” of human lives instead of clear cut divisions, may not always be that easy, when the grant disbursing agencies are also accountable to their national governments and are competing and/or collaborating with other international agencies.

2. Correct me if I wrong, but the article seems to suggest that not only is there a wide variation between human beings and their lives that the imposed categories fail to take account of, but that those variations in human lives and identities are intrinsically tied to the larger issues of poverty, class and caste dynamics. What if one suggests that just like there are variations within the normatively classified MSM-TG groups, the issues of “poverty,” “class” or “caste” involve an equally wide variation and spectrum? It could be argued that “class” and “caste” are not such stable categories either. If that is the case, then more questions get raised – which category should be taken as relevant in a given context, to whom is it relevant, for what purposes etc. It would be about making a choice and decision as to which category to prioritize and how. The moment the issue of prioritization arises, it also often becomes a matter of diluting some of the complexities by creating more “standard” categories, especially, when the donor is formulating a list to disburse funds. It is of course not a “neutral” exercise but the politics with inscribed values in that process of list making also involves wide ranging issues that not only have to deal with the complexities of the “communities” to who or for whom the funds are distributed but include political complexities of international relations, legalities, institutional boundaries etc – very very simplistically put.

3. It is critical to bring forth the complexities of human relations, but donor agencies are part of them and do not operate outside of those complex relations. At some point in time, researchers could build up strong communities to provide specific guidelines and a list of what to look for, what to take account of, and what to ignore. They might not be heard always but it could be a start. My “experience” (partial and biased) suggests that often researchers state that they are not in the “business of providing solutions” or are not there to provide any “prescriptive guidelines.” That is perfectly understandable and I shall not go into the debates of possibility and impossibility of an “objective” all round analysis. But is it at least possible to provide some concrete suggestions by aggregating the complexities – which would also unfortunately mean simplifying them. But I think then there would be a charge of “depoliticization,” isn’t it? But the academic politics, in my opinion, while not doing harm, might also not “help” much in the long run.

4. Another issue that researchers could provide some help with is on the issue of project financing. Since often, the “development” issues revolve a lot around “funding” and imposition of conditionalities – it would help if the researchers could provide alternative sources and end-points of funding, as well as, how a given amount of fund from a given agency could be used, and on what issues.

5. There is a general question on causality that seems to be drawn here: the article states, “These hurdles of representation further worsen the bureaucratic hassles…and corruption or misappropriation of funds at higher administrative levels of state AIDS control bodies (as exposed by this report from West Bengal)”. I read the report but at least from the text, it is not at all clear that the corruption of the WB bureaucracy has anything to do with the problems of representation. Those acts seemed to have been carried out quite independently and do not seem to be related to the development agency’s imposition of classification and people’s resistance to it.

LikeLike