Update: The Hindu has acknowledged the problem with Mr Manash Bhattacharjee’s article not crediting the source of its information, and has edited his article online to give credit to Mr Thanvi. The paper has also added this note at the end of the article: “This article has been edited to include the original source of Che Guevara’s remarks on India, made during the revolutionary’s first visit to the country. All of his quotes have been drawn from Om Thanvi’s ‘The Roving Revolutionary,’ published originally in Hindi in Jansatta and later in English in Himal magazine in December 2007.”

Also see Mr Bhattacharjee’s response in the comments section of this post.

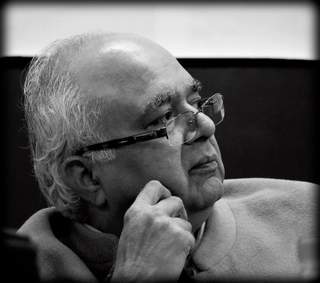

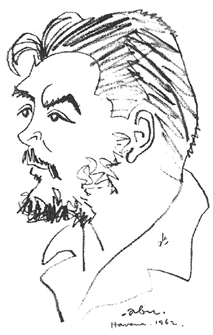

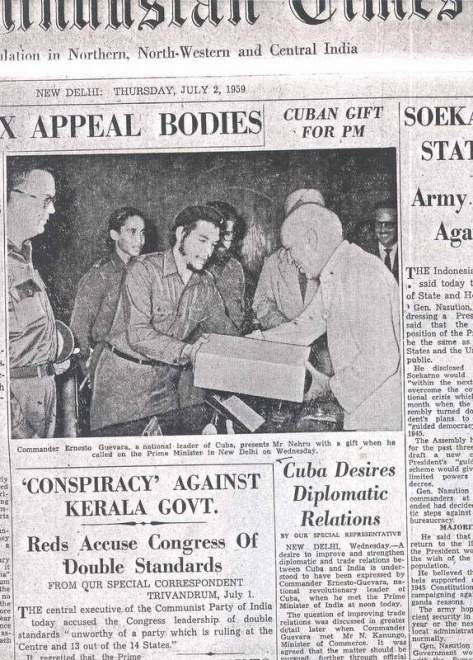

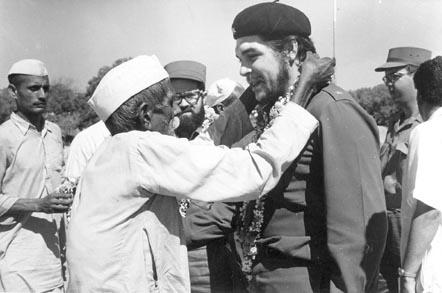

(In August-September 2007, Om Thanvi, editor of Jansatta, a Hindi daily of the Indian Express group, published in his paper a series of articles giving a vivid account of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara‘s historic 1959 visit to India. The articles were accompanied by a few photographs of Che in India: Che talking to peasants in a north Indian village; Che being interviewed by All India Radio at Hotel Ashok where Che and his six Cuban colleagues were staying; Che in a warm handshake with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru at Teen Murti Bhawan, and so on. Jansatta even carried a sketch drawn by the famous cartoonist Abu Abraham, on which Che put his initials on the collar in 1962.

Om Thanvi’s Che series created some excitement in left circles as there was no other recorded memory of that visit. Some Che fans called up Thanvi and expressed doubt regarding the Che visit; one senior CPI (ML) activist even doubted the authenticity of the photographs. Thanvi thus felt the need to tell the story of his Che research.

Thanvi visited Cuba in June 2007. Trying to familiarise himself with Cuba, he read Jon Lee Anderson’s biography of Che. Once in Cuba he realised that Che still held a special place in the hearts of Cubans. He contacted Che’s son Camilo Guevara March and visited Che’s residence, which had been converted into a study centre. With the help of March he got a copy of a report, in Spanish, written by his father about his India visit. He got a few pictures of Che’s India trip and was shown the khukri or small sword which had been presented by Nehru to Che.

Thanvi got the noted translator Prabahti Nautiyal to translate Che’s report from from Spanish into Hindi. Upon his return to Delhi, Thanvi continued his search and went to the Central Government Offices (CGO Complex) looking for official records about the visit. He had a hard time locating it; official documents were not easily traceable as in records his name was not mentioned as “Che”. He was Commander Ernesto Guevara, ‘a national leader of Cuba’, as was Che’s official title.

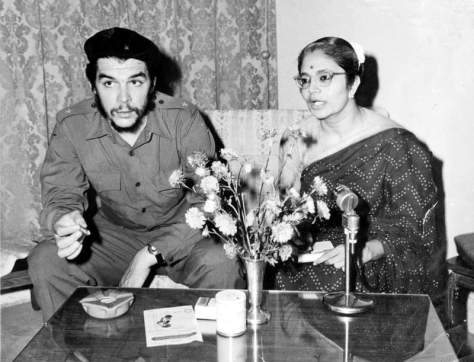

Om Thanvi also traced K.P. Bhanumathy who had interviewed Che for AIR. She showed him her article that recalled the interview. Bhanumathy provided Thanvi some photographs, which were taken during the interview. Thanvi then went to the Hindustan Times building and unearthed reports from their archives about Che’s visit. Than he went to Calcutta to find out facts about Che’s visit to the city.

It was with such painstaking research that Om Thanvi brought us, for the first time, the story of Che’s visit to India, which had otherwise been almost forgotten. Thanvi feels that it was because of Che’s comments against Russian Communism that the Indian Communists chose to forget Che’s visit to India.

Thanvi got his account translated from Hindi into English when The Hindu expressed interest in publishing it. With consent of the then editor-in-chief N. Ram, he sent the article and several photographs to The Hindu. But perhaps the initial interest waned and The Hindu never published it. The article was thus published in Himal Southasian in December 2007.

Five years later, on 23 February 2013, The Hindu published a small article by freelance writer Manash Bhattacharjee on Che’s visit to India, using details that had been unearthed by Thanvi. “I give here a recollection of Che’s visit to India in 1959…” Bhattacharjee writes in the first person, as though he had witnessed Che’s trip first hand. Not citing Thanvi’s work is not only unethical and unprofessional, but also a typical example of how those writing in English have no qualms in Brahminical appropriation of the work of Hindi scholars, even as they go about speaking in the name of the marginal. The result is that others are now citing Bhattacharjee’s article as if it is thanks to his research that we know of Che’s visit to India. The Hindu used three photographs that had been sent to them by Thanvi in 2007, and said the photographs had been obtained “by special arrangement” instead of giving credit to the sources, such as K.P. Bhanumathy or the Photo Division of the Government of India.

Reproduced below is Om Thanvi’s article from the December 2007 issue of Himal Southasian along with a number of photographs collected by him. – Apoorvanand)

~

Che in India

By OM THANVI

With the 40th anniversary of Che Guevara’s death just past, there has been a revival of interest in this iconic revolutionary.

The imposing mansions of Vedado, a posh area of La Habana, tower over a small house that contains a quaint blue room. It is hard to believe such a modest edifice was once the home of Commander Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, the most powerful leader of Cuba after Fidel Castro. The famous revolutionary was well known for his self-effacement. The house is now home to the Centro de Estudios Che Guevara, the Centre of Che Guevara Studies, an institution run by Che’s son, Camilo Guevara March.

A few weeks ago, I visited the Centro to gather information about Che’s little known 1959 visit to India. Since Camilo was just about to leave for Argentina, Che’s motherland, to attend a function on the occasion of his father’s birthday, he instructed Research Officer Lazaro Baccalao to assist me. Baccalao shared a variety of relevant information, such as the names of the delegation members and the follow-up actions taken. He also dug out the report that Che submitted to Cuban authorities upon his return from India and other countries, and showed me a calendar decorated with photographs of Che’s meetings with several major Third World leaders. One photo showed Jawaharlal Nehru with Che. The warmth of their relationship is documented in Che’s report, and is reflected in Nehru’s gift to Che – a khukuri that Baccalao reverently showed.

The ivory-handled weapon was sheathed in a walnut scabbard engraved with a depiction of a woman whose identity Camilo, Baccalao informed me, was eager to learn. I told him that it was not a woman but a goddess, probably Durga, the symbol of shakti. When I noted that there was no better gift for a leader as powerful as Che, Baccalao smiled with pleasure.

Che earned Fidel Castro’s resolute admiration when the two fought together against the Cuban military dictator Fulgencio Batista. In February 1959, when Castro’s revolutionary government was established after two years of guerrilla warfare, he declared Che a “natural-born citizen of Cuba”. Six months later, Castro sent Che on an official tour of Asia, Africa and Europe. As an informal sort of foreign-cum-commerce minister, Che’s goal was to build confidence in and goodwill toward the new government, and to explore markets for Cuba’s main commodities, particularly sugar.

‘National leader’ in Delhi

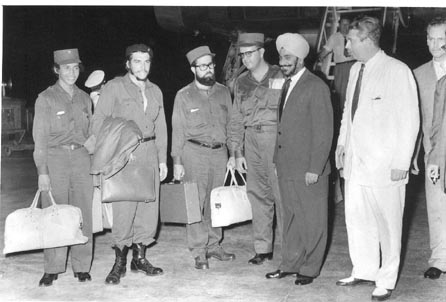

Che left Havana on 12 June 1959. He celebrated his 31st birthday in Madrid, and flew to Delhi via Cairo. His plane reached Palam on the night of 30 June. Since Che had no official position in the Cuban government, this “national leader of Cuba”, as he was described in official communications, was received at the airport by a welcoming committee of one, Deputy Chief Protocol Officer D.S. Khosla, who later accompanied him to the newly built Hotel Ashok in Chanakyapuri.

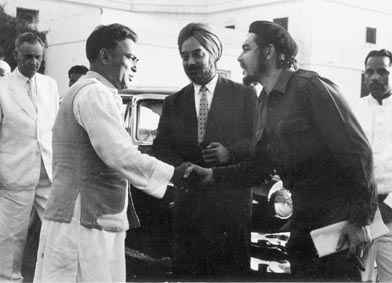

The Cuban delegation accompanying Che was likewise small: a mathematician, an economist, a party worker, a captain of the rebel army, and a single bodyguard. Pardo Llada, a rightwing broadcaster, also joined the delegation in Delhi. Though Llada was ostensibly sent to assist Che, it is rumoured that Castro wanted some respite from his popular daily radio programme in Havana. In any case, Che was not happy to have him, and Llada ended up returning home midway through the trip. On his first morning in Delhi, Che met Nehru in Teen Murti Bhawan, the prime minister’s residence. Nehru had a soft spot for socialist countries, and Che clearly admired the Indian leader. “Nehru received us with an amiable familiarity of a patriarchal grandfather,” Che wrote in his report, “but with noble interest in the dedication and struggles of the Cuban people, commending our extraordinary valiance and showing unconditional sympathy towards our cause.”

Formal talks took place before lunch, and Che explained that Cuba wanted to establish diplomatic and trade relations with India. Though Cuba did have a consulate in Calcutta, India had no diplomatic set-up in Cuba, with the Indian ambassador in Washington instead attending to Indian affairs in Cuba. The two delegations agreed to establish diplomatic missions as soon as possible, and post-lunch plans were made for the Cuban delegation to meet Indian trade officials.

How tasty the lunch was is difficult to say, but Llada, in one of several half-baked stories about Che’s trip, described the occasion in rather disparaging terms: Nehru, his daughter Indira, and her young sons, Sanjay and Rajiv, were all in attendance. The venerable Indian Prime Minister showed exquisite manners, explaining each exotic dish in turn to Guevara and his comrades, while Che, smiling politely, attempted to display some interest. The banquet went on in this fashion for over two hours, but the only words that came from Nehru’s mouth were about the meal in front of them. Finally, Che could stand it no longer and asked: “Mr Prime Minister, what is your opinion of Communist China?” Nehru listened with an absent expression, and answered, “Mr Comandante, have you tasted one of these delicious apples?” “Mr Prime Minister, have you read Mao Tse-tung?” “Ah, Mr Comandante, how pleased I am that you have liked the apples.”

Those who knew Nehru find Llada’s account difficult to swallow. But even if the mealtime conversation was insipid, things picked up in the afternoon. The delegation visited the Okhla Industrial Area, where they saw wood-moulding machines and met with Commerce Minister Nityanand Kanoongo, which proved to be an important meeting for future Indo-Cuban trade relations. In the evening, Che spent half an hour at the Cottage Industries Emporium.

The following day, 2 July, the delegation met Indian Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon. A national daily’s front-page photo of Che smiling broadly while talking to Menon suggests a cordial meeting, as does the caption: “The daring rebel leader is seen in a mellow mood as he chats with the Defence Minister.” The delegation also met senior defence officers and members of the Planning Commission, and visited the Agricultural Research Institute and National Physical Laboratory. At the latter, Che tested the efficacy of a locally designed metal detector by waving it across his shirt pocket. The next day, Che visited a community development project in Pilana, near Delhi, meeting farmers and viewing a school. Later that day, he met with Minister for Community Development and Cooperation S.K. Dey. On the fourth day, he met Minister for Food and Agriculture A.P. Jain, as well as additional bureaucrats within the commerce and industry ministries. During this meeting, Che listed the products that Cuba was hoping to import from India – coal, cotton textiles, jute goods, edible oils, tea, film and trainer aircrafts – and what it wanted to export, including copper, rayon cords for tyres, cocoa and, most importantly, sugar.

His comments on the meeting suggest just how astute he had become about the principles of international trade in such a short period of time: “With the Secretary of Commerce we held a cordial meeting that prepared the ground for future trade negotiations. This can be of great importance. As the standard of living of three hundred eighty million Indians improves, their need for sugar will grow and we will be able to acquire a new and valuable market.” Indeed, Castro once said that whatever work this gun-loving doctor was assigned, he would soon become an expert at it.

Che’s keen interest during his Pilana visit is documented in both his report and in several photos. Apart from photographs of official meetings during the delegation’s five-day visit to Delhi, there are several informal snaps, including one in which the Gandhi-cap-wearing farmers of Pilana are garlanding the revolutionary leader.

In his report, Che reflects on the poor conditions of village schools in words that still ring true till today:

The school, pride of the cooperative, was based on the extraordinary efforts of two teachers who were taking care of five classes that it was running. Haggard children with visible signs of illness on their faces, squatting on the ground, were listening to the explanations of the teacher.

The fact that farmers could be so extremely poor while heavy industry was thriving deeply disturbed Che, as did the inequality of landholdings in India. He found it unjust that “a few have much and many do not have anything.” At the same time, he was deeply impressed by how the Hindu religion protected its cattle wealth, which he saw as the backbone of the rural economy. Both of these understandings would help Che define his own ideologies in later years.

The mysterious Krishna

Though Che was known to be an introvert, one who often spent his time reading and writing poems, his stay in India revealed, perhaps even brought about, a far more outgoing and entertaining side. At the residence of the Chilean ambassador in New Delhi, for instance, he demonstrated how to do sheershaasan (a headstand), spontaneously putting his head on the ground and raising his feet towards the sky in the midst of a lively discussion.

His letter-writing in Delhi also suggested Che’s growing extroverted dimension. In this epistle to his mother, Che confesses his nervousness about botching diplomatic niceties, but also confides that his sense of a great calling was giving him the confidence to influence others. “Now India, where new protocol complications produce in me the same infantile panic,” he writes, referring to deciding how to respond to various official greetings. He goes on:

Something which has really developed in me is the sense of the massive in counter-position to the personal; I am still the same loner that I used to be, looking for my path without personal help, but now I possess the sense of my historic duty. I have no home, no woman, no children, nor parents, nor brothers and sisters, my friends are my friends as long as they think politically like I do, and yet I am content, I feel something in life, not just a powerful internal strength, which I always felt, but also the power to inject others, and an absolutely fatalistic sense of my mission which strips me of all fear. I don’t know why I am writing you this, maybe it is merely longing for Aleida [his daughter]. Take it as it is, a letter written one stormy night in the skies of India, far from my fatherland and loved ones.

A hug for everyone, Ernesto

On 5 July, Che and his delegation left Delhi for other parts of India. Through the records of Cuba’s Radio Rebelde, we know that they may have seen Lucknow’s Institute of Sugar Investigation, though no other sources confirm this visit. What can be corroborated is that the delegation was in Calcutta on 10 July, as an English-language daily published a photograph of Che’s visit to a factory in Agarpada. A senior officer from Calcutta told me that Che also met with B.C. Roy, then Chief Minister of West Bengal. Shockingly, the Calcutta communists – at a time when the Communist Party of India had not yet split – completely ignored the presence of this great leader of the Cuban revolution.

In Calcutta, Che met a mysterious though influential figure, whom he refers to as ‘Krishna’ in his report. Though there is no clue to Krishna’s identity, it is clear that the meeting had a great and long-lasting impact on Che, particularly with regard to his thinking about nuclear weapons:

We had an opportunity of meeting a wise person called Krishna, who seemed like a person far above our world of today. He with his simplicity and humility, a characteristic of his people, talked to us for quite some time, stressing the need for using the entire resources and technical capacity of the world for peaceful use of the nuclear energy. He strongly condemned the absurd politics of those who dedicate themselves to storing hydrogen bombs in their international discussions.

Several of my friends have suggested that ‘Krishna’ could have been J. Krishnamurti, but I feel that this is unlikely, as Krishnamurti had left Delhi in May 1959 for a three-month visit to Kashmir. Whoever Krishna was, an hour after Che returned to Havana from his 17-country visit he held a press conference, at which he gave the following account of his visit to India:

People of India were sympathetic toward the Cuban people and we saw that they are trying to solve the problems of too little cultivable land and the large estates. While talking with Krishna, the learned Indian, we became aware of the evils of the means of mass destruction and when we saw the frightful truth at Hiroshima we felt ashamed for having been glad at times when the atomic bomb was dropped on that city by the democratic powers during World War II.

An anecdote shared by one of the delegation members sheds further light on the extent to which Che continued to value what he learned from Krishna. Apparently, when the Cuban ambassador in Tokyo told Che that they would visit the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to pay homage to the Japanese soldiers who died in World War II, Che angrily retorted, “No way I’ll go! Where I will go is to Hiroshima, where the Americans killed 100,000 Japanese!”

The practical revolutionary

Che’s newfound respect for Mohandas K. Gandhi and the Satyagraha movement also merits special mention. When Che was in Delhi, journalist K.P. Bhanumathy interviewed him for All India Radio. Bhanumathy, who still lives in Delhi, told me that Che used to speak like an astrologer – thoughtfully, with long pauses. “If we ignore his military uniform, heavy boots and Monte Carlo cigar,” she recalled, “then his simplicity and politeness was like that of a holy priest.” During the 1959 interview, Bhanumathy bluntly said to Che, “You are said to be a communist but communist dogmas won’t be accepted by a multi-religious society.” Che’s reply is telling:

I would not call myself a communist. I was born as a Catholic. I am a socialist who believes in equality and freedom from the exploiting countries. I have seen hunger, so much suffering, stark poverty, sickness and unemployment right from my very young days in [Latin] America. It is happening in Cuba, Vietnam and Africa – the struggle for freedom starts from the hunger of the people. There are useful lessons in the Marxist-Leninist theory. The practical revolutionary initiates his own struggle simply fulfilling laws foreseen by Marx. In India, Gandhiji’s teachings had its own merit which finally brought freedom.

Photo by P.N. Sharma

According to Bhanumathy, Che expressed great respect for both Gandhi and Nehru. At one point, Che noted, “You have Gandhi and an old philosophical heritage; in our Latin America we have neither. That is why our mindset has developed differently.” In his report, Che also mentions Gandhi and the role of non-violence in the Indian struggle for independence. Perhaps alluding to what Krishna said to him in Calcutta, Che observed:

In India, the word war is so distant of the spirit of the people that they didn’t resort to it even at the tense moments of their struggle for independence. The great demonstrations of collective peaceful discontent forced the English colonialism to leave forever the land that they devastated during one hundred and fifty years.

Ultimately, it was the understanding that Che came to about social justice while in India, rather than those about non-violence, that would significantly affect his final years. From India, Che went on to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and onward to Burma, before travelling on to Indonesia and Japan. On his return journey, he swung through Singapore and stopped in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). After pushing on through a few countries in Africa and Europe, however, Che began to hear rumours about Castro’s ill health. Being unable to establish telephone contact, he returned to Havana on 8 September 1959.

Though Castro immediately gave Che several significant responsibilities, including the post of industries minister, Che soon got tired of office work. He also became fed up with the Russian type of socialism, which he disparaged for using the methods of capitalism to exploit Third World countries for the financial and strategic gains of Russia. Leaving his government office, Che returned to the jungle and to his guns. Even while in India, he had been dreaming about fomenting revolutions in other parts of Latin America. According to one of the members of the Cuban delegation, Che had said one night:

There’s an altiplano [a high plateau] in South America. There is Bolivia, Paraguay, an area bordering Brazil, Uruguay, Peru and Argentina… where if we enter a guerrilla force, we could spread the revolution all over South America.

Back in his revolutionary guise, Che attempted to bring about socialist revolutions in the Congo (now Zaire) and Bolivia. Why these exploits failed constitutes another story altogether. Nonetheless, Cubans and other Latin Americans continue to see Che Guevara as no less than a heavenly prophet. His aspirations prompted him to abandon the corridors of power, thrusting him instead onto the minefields of a violent fight for the freedom of others. Though Che was executed on 9 October 1967, his ideas have since inspired untold thousands to rise against tyranny. Forty years after his death, his vision continues to fire many a revolutionary.

(First published in Himal Southasian, December 2007, under the title, ‘The Roving Revolutionary‘)

See also:

- Adnan Farooq: When Che visited Pakistan

- K Gajendra Singh: A meeting with Che Guevara

Kudos to Apoorvanand for having raised an important issue regarding the highly asymmetrical relationship between the English intelligentsia and the Indian language writers. Least one expects is a clarification from The Hindu and Manash Bhattacharjee.

LikeLike

Very typical of a certain kind of radical posturing that talks down to the whole world about ‘ethics’ but has not the slightest qualms in such appropriation of credit – after all every thing is justified for the cause! In Manash Bhattacharjee’s case, of course, it is difficult to say what the cause is – anything that will get some applause – even momentary: Levinas in some circles, Gandhi in others, Maoism and Arundhati Roy in yet others and Ambedkar in yet yet others!! Thanks Apoorvanand for this post.

LikeLike

Nice post. Aside from all the theory/posturing and implications thereof, it reminded me of the reading room on the main road at Fort Cochin which has a nice lot of Che in India memorabilia.

LikeLike

The Frontline magazine had carried a piece – I think it was a reproduction of Che’s impressions after his visit to India. This forms part of his reflections: “while the hurricane of agrarian reform sweeps away the big land holdings of Camaguey in one grand wave and advances unstoppable through the entire country giving free land to the farmers, the great Indian nation treads cautiously with oriental parsimony, convincing the big landlords of the justice of giving the land to the tiller and the farmers of paying a price for this land, thus making almost imperceptible the transition of one of the most noble, sensible and pauperised masses of entire humanity from misery to poverty.”

“From misery to poverty” captures the scene so perfectly..

LikeLike

Manash Bhattacharjee writes in an email titled ‘a clarification’ to Om Thanvi:

***

Mr Bhattacharjee is lying through his teeth about Kafila not having published his response because he hasn’t submitted any. What does he mean when he says he ‘somehow’ didn’t give credit to Om Thanvi. Even it was an ‘accidental ommission’ (which it wasn’t, Mr Bhattacharjee was clearly trying to sound as though his information was first hand) why can’t he show the grace to say so much as a ‘sorry’ to Mr Thanvi? Shame is a revolutionary sentiment, after all.

LikeLike

Someone has sent me this text posted at 5 am by Manash Bhattacharjee in Facebook, where again he claims that his response may not be or has not been published by Kafila.As an administrator here, I want to reiterate that this is false, that he did not submit any comment,or at least we did not receive it. Whatever the case may be, I am pasting his Facebook clarification below. It is an interesting contrast from his letter to Mr Thanvi.

Meanwhile, The Hindu has acknowledged the problem with Mr Manash Bhattacharjee’s article not crediting the source of its information, and has edited his article online to give credit to Mr Thanvi. The paper has also added this note at the end of the article: “This article has been edited to include the original source of Che Guevara’s remarks on India, made during the revolutionary’s first visit to the country. All of his quotes have been drawn from Om Thanvi’s ‘The Roving Revolutionary,’ published originally in Hindi in Jansatta and later in English in Himal magazine in December 2007.” Also see Mr Bhattacharjee’s response in the comments section of this post.

LikeLike

To reiterate what my colleague Shivam has already said, we on Kafila have received no comment or response directly from Mr Bhattacharjee. His contention that we are not publishing his response is untrue. Not having received anything from Mr Bhattacharya we have nonetheless carried his responses posted in other fora.

In his Facebook posting Mr Bhattacharjee insinuates that Apoorvanand’s raising the issue of credit is an “aspersion” and not fact:

.

But this is not according to Apoorvanand. This is according to Mr Bhattacharjee who in his personal letter to Mr Thanvi admits to not having credited his source.

His justification for this is that because he was writing in a newspaper, basic academic citational protocols somehow do not apply. This is the most ridiculous thing I have heard. Unless a source is at risk, or is sharing classified information and does not wish to be named, journalists credit sources. How else is the veracity of the information to be ascertained? Further, Mr Bhattacharjee’s piece is not reportage (where the question of sources not being named even arises). It is an opinion piece. He says so himself. In which case there is absolutely no justification for not crediting Mr Thanvi. And finally Mr Bhattacharjee has this to say:

What does this even mean? Firstly, Mr Bhattacharjee omitted to credit not just a series of conversations between him and Mr Thanvi, but printed quotes which appeared in an another publication. Secondly, of what use are quotes attributed to no one? Perhaps he assumes we are all clairvoyant and will magically intuite the unnamed source (sacrificed in the essay much like the unnamed soldier). Or, perhaps this is some new ghost citation protocol unknown to all except Mr Bhattacharjee.

LikeLike

i feel terrible bad all this happened towards che. who is our constant source of inspiration for fight towards equality. somehow manash has not got to the spirit of che. who after winning the battle in Cuba went on the mission of recreating it all through world and laid down his life.

LikeLike

This is a witch hunt, Kafila has lined up its warriors on one side and got them all to attack Manash. Considering that Manash himself has admitted to the omission, I dont think, the systematic attack was necessary at all. Especially considering that the first attack, it self used adjectives to demean, Manash.

The response of the kafila team proves to me that the allegations, Manash makes about the ‘moderating tendencies of Shivam Vij and his team ring true.

What surprises me, is all the big talk on matters of national, International and local concerns which are discussed here and in lovely ways, have not taught the members of this organisation/group any humility.

It is a shame, this righteousness that you exhibit. It leads me to believe that this post on Che was an effort to get back at Manash.

LikeLike

I don’t want to respond to the rest of your charges, but it’s funny you write that ‘Considering Manash has admitted to the omissions.. ‘ because Manash has done so only as a result of this post by Apoorvanand, and does not have the couth to say sorry to Om Thanvi despite admitting the omission, and plays victim on Facebook while asking Om Thanvi to ‘Please acknowledge my intention was not…’ — after all this if you can still defend Manash then bravo! If you don’t see a contradiction in Manash Bhattacharjee asking Om Thanvi to ‘excuse’ him and his claiming at the same time that the ‘aspersions’ cast by Apoorvanand are ‘silly and ridiculous’ then you are truly a great friend of Mr Manash Bhattacharya.

LikeLike

Che is the LEft of Centre contemporary of Narendra Modi, the man you love to hate. So paranoid, witch hunting politicians are okay if they are from the left ? Che is a proven mass murderer. The Che portrayed in The motorcycle diaries is a piece of fiction. cmon guys

LikeLike

You are talking nonsense Che was the man of the people and he murdered no one.

A qualified doctor chose to fight for the downtrodden people of the world.

Long Live this great son of the masses.

Now N Modi is a mass murderer.

LikeLike

You would love to think so coz you never lived in a place that Che ruled. Let the Cuban exiles say that. Here is a qutore from your day dreaming man of the people – “Hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective and cold-blooded killing machine. This is what our soldiers must become…” What lovely, soothing words indeed.

I am sure you are one of those guys who owns the Tshirt with Alberto Korda’ picture of Che in it.

LikeLike

Spot on with this write-up, I seriously believe this

site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the advice!

LikeLike

bravo comrade che’

LikeLike

red salute red salute comandante.. ‘ che ‘

LikeLike

A nice article. Why do I believe the “how are the apples” exchange actually took place?

But guys, I fail to understand all the hullabaloo about giving credit and journalistic ethics etc. I read the article by Manash too following on from here. Its kind of a gist of this with some personal observations thrown in. Of course he erred if he did not give credit. But “Brahminical appropriation” “asymmetrical relationship” … wow, get a life guys

LikeLike

what do you expect from a PM who is allowing two small children (who later proved their intelligence) in a meeting with Che; he never wanted to be on wrong side of anybody.. here Che is asking him to comment on China.. whom he gifted UNSC seat… i can imagine. In Dynasty by Bhatia… one American said … Nehru is in love with his voice.. he has to just talk.. read the book.

LikeLike

OM Thanvi mentions about the meeting of Che with a “The mysterious Krishna”. I think the mysterious Krishna could very likely be Krishna Chaithanya , a scholar, originally from Kerala who was living in Delhi / Calcutta then. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krishna_Chaithanya) . As Chairman or member of functional committees he has been associated with over a dozen national cultural organizations and institutions in India. He is a recipient of the ‘Critics of ideas’ award (1964) from the Institute of International education, New York. He was honoured with a D Litt (Honoris Causa) by the Rabindra Bharati University in 1986 and received the Padma Shri from the Indian Government in 1992.

LikeLike

The unidentified ‘Krishna’ might be Mr Ramkrishna Mukherjee , professor of sociology of Indian Statistical Institute at the time of Che Guevara’s visit to Calcutta. He was famous internationally at that time. He was the author of many books like Six Villages of Bengal, Sociology of Indian sociology, Rise and fall of East India Company etc. He was very close to Mr Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, the founder of Indian Statistical Institute of Calcutta. He was a very wise man and possibily he had a talk with Che Guevara and his teammates in ISI, Calcutta(Kolkata).

LikeLike