Guest post by SAGAR DHARA

The Aam Admi Party (AAP) has won a spectacular victory in the Delhi assembly elections and will form a government shortly. The party’s manifesto 2015 (http://www.aamaadmiparty.org/AAP-Manifesto-2015.pdf) promises to do many things—some positive, e.g., passing a Swaraj Bill and some that are not so positive, e.g., setting up pithead power plants to supply power to Delhi. Here are a few practical suggestions that may help AAP and its supporters to strengthen people’s participation in grasroot self-governance.

Participatory budgeting

AAP’s proposed Swaraj Bill is aimed at strengthening grassroot self-governance in Delhi mohallas and community neighbourhoods. Mohalla committees are designed to deal with local issues. However, they can also be used as platforms for Delhi’s polity to participate in decisions that that affect all of Delhi through a process called participatory budgeting.

Participatory budgeting first began in 1990 in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre. In the first quarter of every year, communities hold open house meetings every week to discuss and vote on the city’s budget and spending priorities for their neighbourhood. Later, city-wide public plenaries pass a budget that is binding on the city council. The results speak for themselves. Within seven years of starting participatory budgeting, household access to piped water and sewers doubled to touch 95%. Roads, particularly in slums, increased five-fold. Schools quadrupled, health and education budgets trebled. Tax evasion fell as people saw their money at work. People used computer kiosks to feed communicate suggestions to the city council’s website.

Participatory budgeting is now being done in 1,500 towns around the world—Europe, South America, Canada, India—Pune, Bengaluru, Mysore and Hiware Bazar in Maharashtra. Twenty five years ago, Hiware Bazar was like any other drought-prone village in Marathwada. Today its income has increased twenty-fold and poverty has all but disappeared.

Aam admi-friendly information search engine

India has a Right to information (RTI) Act. It has been used effectively by a small fraction of the educated who know how to locate the information they want. But the vast majority of Indians cannot use the RTI Act as they do not how to access the information they want. The RTI Act empowers people with the right to get information, but does not tell them how to access it. What is required is an aam admi-friendly information search engine. To design such a search engine requires us to understand a wee bit of information theory.

There is a distance between an information seeker and the information that she seeks. This distance can be measured in terms of effort (that includes time) and cost. For example, a traveller going from Lonavala to Pune wishing to know whether her Mumbai-Pune train is on time will have access this information either from the net or by calling railway enquiries.

In this case, only one piece of information is sought and is available in one place and the effort and cost to get it is small. But if the traveller wanted to know the status of all Mumbai-Pune trains on a particular afternoon between 2-5 pm, the effort and cost increases. Though the quantum of information has increased, the effort and cost of accessing it does not increase significantly as it is all still available in a single place.

If the query is such that information sought is available at several places, the search becomes more complicated and will take more time and effort. For example, if a researcher wanted to know how much land was under paddy in Badaun district last year, he would have to collect this information from land records maintained in each village in Badaun district and then compile them on a spreadsheet. The information is spread horizontally across an entire district.

If however, the researcher wishes to know how much land was earmarked for paddy by the district authorities and how much was actually under paddy, the researcher would have to go to the district headquarter to get the former information and then to all villages to get the latter information. This location of this information is spread vertically and horizontally, and therefore requires more effort and cost to access.

A lot of the information that Dilliwallas, or for that matter any aam admi, may want is spread vertically and horizontally, e.g., what are all the Delhi Government schemes that a mohalla can avail of for water, sanitation, baalwadis, pension schemes for the poor, mid-day meal schemes for government schools, etc.? Is it possible to design a search engine that an aam admi can use to access this information quickly and with minimum effort and cost, and most importantly without computer skills?

Yes. We require an aam admi-friendly information search engine that works on different platforms—manual platforms, computer networks and phones. The way that the RTI works presently, the information seeker has to travel the entire distance to where the information is located. She has to first locate the information, and then by ask for it.

If the information were to travel half the distance to the seeker by advertising itself, “here I am, if you want me,” the distance between the information and its seeker reduces. This has already been done on the internet by search engines. But only the net-savvy can use them, not the aam admi. Moreover, a lot of information from government, particularly about schemes and budgets, is not always available on the net.

To overcome these obstacles, a low-cost platform can be used—notice boards outside every government office detailing the information available in that office under six major heads as outlined under. These information heads are common to all government ministries and departments, regardless of whether they pertain to law and order, health, environment, industry, or any other subject.

- Policy deals with government’s intention in a particular subject.

- Organization deals with structure, responsibilities/duties and powers of functionaries at different levels.

- Plans deal programmes, schemes, and budgets.

- Work implementation deals with status of completed and ongoing programmes, schemes, financial statements.

- Records deal with decisions, studies, surveys, maps.

- Performance deals with evaluation reports, statistics.

Each of these major heads can be broken into further sub-heads appropriate to each ministry or department. For example, the Environment Department may have information on air and water quality filed separately. Again under air quality, information may be separated by type of area, e.g., industrial, residential, commercial, and mixed areas.

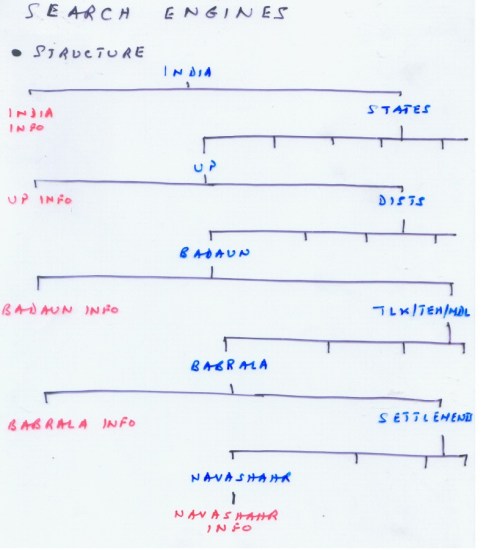

Government offices form a hierarchy, at the top, India-level ministries, below that state-level offices, then district, tehsil and village-level offices. An information hierarchy follows the organizational hierarchy. The ministry will have information about India as a whole. The resolution of information that it may have on every state may not be as high as what is available at the state-level. To increase the speed of a search it is important to understand that information under a particular topic is stacked in such a hierarchy.

Information hierarchy

Besides an information-head notice board, each government office will on demand, provide a hand-out containing the same information as on the board to any aam admi who may ask for it. A comprehensive information availability chart for all Delhi Government ministries and departments at all levels can also be made available on other platforms such as the internet.

To help a manual information searcher, information search offices, much like the yester-year STD booths, can be established and operated by private persons in different parts of the city. Such offices can access the internet to locate the information required by an aam admi. Information search offices can provide jobs for the under-privileged—women, dalits, differently abled, transgenders, etc., who often have difficulty finding regular employment. Searches done by such offices may be charged at approved rates.

India already has the experience of using such devices. Before RTI became law in India, public boards carrying information on daily receipt and disbursement of food grains were ordered to be put up outside ration shops in Madhya Pradesh. Immediately after, food grain shortages in ration shops disappeared.

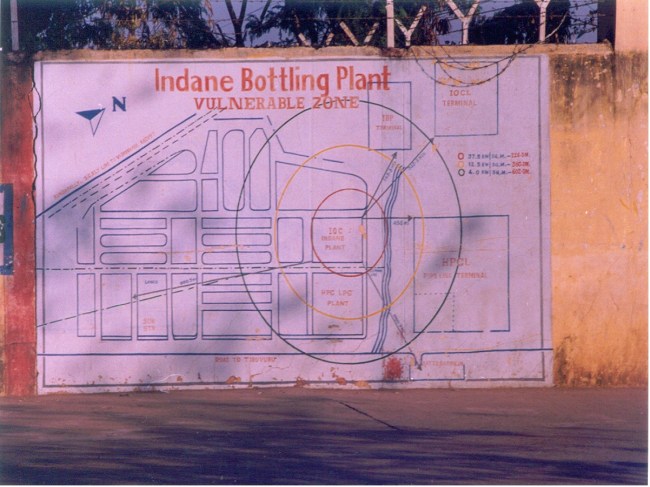

Fifteen years ago, industrial plants in Andhra Pradesh were ordered to put up public notice boards outside their main gate with information regarding the compliance conditions that regulatory authorities had asked them to follow, the latest environmental quality data around their plant and the maximum vulnerable zone in the event of catastrophic accidents. Such boards were put up by industry for some time, but lapsed as industry lobbied against them and there was insufficient push from people to continue with this practice.

Maximum possible vulnerable zone of a catastrophic accident at the LPG bottling plant at Vijayawada

Environmental quality data at Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd’s Visakhapatnam plant

The author belongs to the most rapacious predator species that ever stalked the earth—humans, and to a net destructive discipline—engineering, that has to take more than a fair share of the responsibility for bringing earth and human society to tipping points. You can write to him at: sagdhara@yahoo.com

Reblogged this on Just being me, Ali.

LikeLike

Thanks Sagar. Notice boards have been effectively used in some places with good impact. In addition to notice boards, I feel that an improved version of proactive disclosure, also mandated for all public authorities, will help. As of now, this section often just clerically meets the requirements of the Act, but is not kept updated and is not citizen friendly. Agree that this too is easily accessible to people who can access internet, but those who can access it (will be many in Delhi, I suppose) can pass it in to those who can not. All service providers in Delhi should be brought under RTI. In addition to this, I feel that the Right to Hearing jan sunwai’s of Rajasthan could be replicated in Delhi. This will improve grievance redressal to a large extent.

LikeLike

In general, postings on Kafila are excellent and very thought provoking, especially because they point to a different / alternative future. Sagar Dhara has maintained the tenor of Kafila in his article, provoking in me 2 thoughts.

1) As rightly pointed out, getting data & information to the people to make the RTI Act more effective is a MUST. I realized the immense amount of free service that the U.S. government provides to its citizens (yes, even in the U.S.!). I realized this when, as a student, I was fending for myself by working part-time at the university library. I was given the job of cataloging U.S. government publications. Back then (when there was no Internet), materials were paper-based and micro-fiches. Data and information were varied and included details of proceedings and hearings of the Congress / Senate and their committees, Acts passed by the Congress / Senate, and patent filings. The latter raised my curiosity, prompting me to look through the contents. What I realized was that the U.S. market functioned on a bedrock of fundamental and free services provided by the government. Entrepreneurs were being provided with data / information FREE and made accessible through libraries that already existed around the nation. This encouraged entrepreneurs easy access to whatever they needed and could leverage that information for coming up with more innovations of their own.

Therefore, key message is: Thousands of Information Kiosks may need to be built within much deeper learning and knowledge (not just data / information) accessible and dissemination centers (perhaps, 1 per 1,000 persons living in that locality), to make these more effective, locally funded and without bureaucratic hindrances.

2) While I am all for local governance, I am also somewhat suspicious of what that might mean given our traditional patriarchal and authoritarian practices that bar women and various social segments from participating in decision-making and accessing information.

Long back, while working on a project, I had encountered the failure of local governance in a remote village in the Kuchh region in Gujarat. During my visit the village Panchayat head was a lady (as per the Panchayat Act which ensured women’s participation in Panchayats and also ensured rotation of the panchayat head from men to women). Despite such an opportune moment the Panchayat men were calling the shots on as an important a topic for women as water supply to households. Despite women having to fetch water for the households’ needs (washing, bathing, cooking, taking care of children, etc.) men were deciding on the important aspects of village water supply.

In Haryana we have seen how Khap Panchayats functions on issues related to women-men relationships, demonstrating that unenlightened local governance can be more oppressive than governance from a remote center.

Key message: To take local governance forward we need to put in place certain social audit functions that should haul up non- or mal-functioning local governance institutions.

LikeLike