Via NITYANAND JAYARAMAN

Koodankulam: Curb on Free Speech

Video Interviews with eminent legal scholar Dr. Usha Ramanathan and Adv. R. Vaigai, a senior lawyer from the Madras High Court.

Since March 19, 2012, when Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalithaa announced that work on the controversial Koodankulam nuclear plant could be resumed, and even before that actually, the protesting villagers have been at the receiving end of a vicious state led campaign to paint their non-violent struggle as a violent one, and to crush their campaign into silence by using harsh sections of the Indian Penal Code. More than 7000 cases of “sedition” and “waging war against the Government of India” have been filed just in the Koodankulam police station just between September and December 2011. These are part of 107 cases filed against 55,795 people during the same period. That is probably more than in any other police station in India. Certain sections of the media too have played the role of a willing partner in propagating the State’s propaganda. In pursuing this counter-campaign against its own people, the State Government has placed itself above the law of the land and pursued an openly anti-democratic agenda.

See interviews in two parts at at

1. chaikadai.wordpress.com

2. chaikadai.wordpress.com

PRESS RELEASE

Cases against K-protestors a parody of law: Fact Finding Team

18 April, 2012. CHENNAI – A fact-finding team headed by senior journalist Sam Rajappa confirmed that the Government had indeed restricted movement of essential goods and people in the days following the Chief Minister’s March 19th declaration announcing her support to the nuclear plant. The report, which was released at a press conference in Chennai, noted that the spirit of opposition to the nuclear power plant was very high, and warned that arresting the leaders could lead to a serious law and order problem in the region.

Continue reading Updates from Koodankulam →

Mrs Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, represented the Rai Bareli seat in the Lok Sabha. On 12th June 1975 she was unseated on charges of election fraud and misuse of state machinery in a landmark judgement by Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha of the Allahabad High Court. Fakhr-ud-Din Ali Ahmad, the then President of India, declared internal emergency on the 25th of June, on the recommendation of a pliable cabinet presided over by Mrs G. The people of India lost all civil liberties for a period of 21 months.

Mrs Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, represented the Rai Bareli seat in the Lok Sabha. On 12th June 1975 she was unseated on charges of election fraud and misuse of state machinery in a landmark judgement by Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha of the Allahabad High Court. Fakhr-ud-Din Ali Ahmad, the then President of India, declared internal emergency on the 25th of June, on the recommendation of a pliable cabinet presided over by Mrs G. The people of India lost all civil liberties for a period of 21 months.

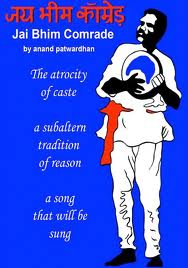

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.