Delhi, Or Dilli has been a city and a capital for a long time and even when it was not the capital, during the Lodi and early Mughal period, and later between 1858 and 1911, it continued to be an important city. We are of course talking of what is historically established and not of myths and legends. During this period there have been 7 major and several minor cities within the territories now identified as the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCR-Delhi). New Delhi is the eight city. This piece marking the hundred years of the shifting of the colonial capital to Delhi from Calcutta in 1912, will talk about both Shahjahanabad and New Delhi. We will see how Shahjahanabad the once most powerful and rich city of its time and the last capital of the Mughals was gradually ruined, plundered and virtually reduced to a slum while next door arose, a new enclave of Imperial grandeur known now as New Delhi. Continue reading Delhi 1803-2012: A Brief Biography

Category Archives: Culture

Resisting Culinary Fascism: Nabanipa Bhattacharjee

Guest post by NABANIPA BHATTACHARJEE

At the end of last month (March 2012) students of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi under the banner of a recently formed group called the New Materialists (NM) organized a public meeting to debate the issue of (dis)allowing certain kinds of food – beef and pork in particular – on the campus. The group, as one of its members Suraj Beri said, intended to petition the university administration to allow the sale of beef and pork in the canteen(s), and fight for inclusion of the same in the hostels’ menus; it was a struggle, as the NM declared, against the Brahmanical dietary impositions on Dalits and other minority community students of JNU. In fact, Francis (JNU students of the 1990’s would remember the man from Kerala) who ran a canteen at the basement of the School of Social Sciences II did serve beef curry on Saturdays, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that there would be more than a mad rush for that. However, he was pressurised – by Hindu right wing groups and other similar forces – to stop the sale of the “forbidden” food, and the canteen was eventually closed down.

Continue reading Resisting Culinary Fascism: Nabanipa Bhattacharjee

Forget Hair-Oil-Powered Indulekha, Remember the Muditheyyam

Well, the truth is that I care two hoots for Indulekha Hair Oil, their stupid ads, and the wide-eyed chubby-cheeked teenage girls who they usually cast as epitomes of Malayalee feminine grace. All of Mallu FB world is agog with discussion about a brainless ad for the Indulekha Hair Oil, in which a fiery-looking woman whose dress-style follows the dress conventions of our Malayalee AIDWA Stars, bursts with indignation over the terrible harassment that women with long hair face on buses, how we are all forced to cut off “the hair that we have” (‘Ulla mudi’) and go about with short hair “like men” because of this horrible injustice, and finally, how we all ought to grow our hair long (and let it down, possibly) and hit back at such harassers. This stupid ad is actually only one among other stupid ads for this hair-oil which uses currently-common ideas like ‘women’s collectives’ (stree koottaimakal). All of them are jarring since the concepts they use, and what they aim at, simply don’t mix.Part of the outrage has been fueled by the fact that the ad uses as a model Sajitha Madathil, who is well-known as a feminist theatre activist in Kerala. Continue reading Forget Hair-Oil-Powered Indulekha, Remember the Muditheyyam

Well, the truth is that I care two hoots for Indulekha Hair Oil, their stupid ads, and the wide-eyed chubby-cheeked teenage girls who they usually cast as epitomes of Malayalee feminine grace. All of Mallu FB world is agog with discussion about a brainless ad for the Indulekha Hair Oil, in which a fiery-looking woman whose dress-style follows the dress conventions of our Malayalee AIDWA Stars, bursts with indignation over the terrible harassment that women with long hair face on buses, how we are all forced to cut off “the hair that we have” (‘Ulla mudi’) and go about with short hair “like men” because of this horrible injustice, and finally, how we all ought to grow our hair long (and let it down, possibly) and hit back at such harassers. This stupid ad is actually only one among other stupid ads for this hair-oil which uses currently-common ideas like ‘women’s collectives’ (stree koottaimakal). All of them are jarring since the concepts they use, and what they aim at, simply don’t mix.Part of the outrage has been fueled by the fact that the ad uses as a model Sajitha Madathil, who is well-known as a feminist theatre activist in Kerala. Continue reading Forget Hair-Oil-Powered Indulekha, Remember the Muditheyyam

An Unrecorded Festival – Pictures from Parliament Street: Siddhi Bhandari

April 14 was Ambedkar’s birth anniversary. There is no single pan-India political icon, certainly not Gandhi, whose birth and death anniversaries are celebrated as public festivals, by the public, in the way the Ambedkar’s is. Some newspapers on 15 April typically had photos of the top leaders of the country paying homage to Ambedkar but that’s about all. When historians turn these pages they will not find, in the first drafts of history, any reports about how people celebrated Ambedkar’s birthday like a festival. They will not find a record of the singing and dancing, of drums and plays, of Dalit housing socities and employees’ unions holding celebrations bang under the nose of the Indian Parliament at Parliament Street as much as in Dalit bastis is villages across India. Such is the public ignorance of this celebration at Parliament Street in Delhi that most Delhites enjoying a free holiday don’t even know about it. Parliament street is where SIDDHI BHANDARI took these photos in 2010.

Review: ‘Behind the Beautiful Forevers’ by Katherine Boo

Guest post by MITU SENGUPTA

In a remarkable book about slumdwellers in Mumbai, Katherine Boo brings to light an India of “profound and juxtaposed inequality” – a country where more than a decade of steady economic growth has delivered shamefully little to the poorest and most vulnerable. But though indeed a thoroughgoing and perceptive indictment of post-liberalization India, the book fits into a troubling narrative about the roots of India’s poverty and squandered economic potential.

This is a beautifully written book. Through tight but supple prose, Boo offers an unsettling account of life in Annawadi, a slum near Mumbai’s international airport. In Boo’s words, this “single, unexceptional slum” sits beside a “sewage lake” so polluted that pigs and dogs resting in its shallows have “bellies stained in blue.” It is hidden by a wall that sports an advertisement for elegant floor tiles (“Beautiful Forevers” – and hence the title). There are heartrending accounts of rat-filled garbage sheds, impoverished migrants forced to eat rats, a girl covered by worm-filled boils (from rat bites), and a “vibrant teenager,” who kills herself (by drinking rat poison) when she can no longer bear what life has to offer.

Continue reading Review: ‘Behind the Beautiful Forevers’ by Katherine Boo

Artists protest against coup in Maldives

Here is a report on artists protesting against a coup in our neighbourhood that landed in my inbox recently. You would have thought that the Indian media would be as interested in what happens in the Maldives as it is in what happens in some of our other neighbouring countries. But sadly, that is not the case, and so, one gets to hear little of what happens in the Maldives, even though you get to see it often as an unnamed exotic locale or a little beach side remance in Bollywood films.

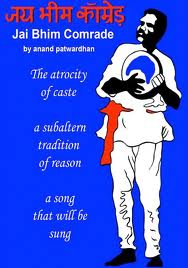

Jai Bhim, Comrade Patwardhan

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.

Ambedkar – A poem by Ravikumar

Guest post by RAVIKUMAR

Under the scorching Sun

Under the scorching Sun

in the shadow of a tamarind tree

there assembled a small crowd

children, women and men

words about Ambedkar,

Dalit rights and Women’s rights

breezed over

sweating faces

When we sow

Some seeds fall in bushes

Some on rocks

Some on dry land

Some in ponds

Some on wet land

Who knows–

who is the wet land

(Ravikumar is a well-known activist and theoretician of the Dalit movement in Tamil Nadu. A former legislator in the Tamil Nadu legislature, he is general secretary of Viduthalai Ciruthaikal Katchi.)

Previously by Ravikumar in Kafila:

A Hundred Years of Manto

“Here lies buried Saadat Hasan Manto in whose bosom are enshrined all the secrets and art of short story writing. Buried under mounds of earth, even now he is contemplating whether he is a greater short story writer or God.”

May 2012 will mark the hundredth birth anniversary of the man who wrote that epitaph for himself, Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955). One cannot help but compare Manto’s centennial to Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s last year, preparations for which had begun much in advance. There seems to be an odd silence about Manto. Continue reading A Hundred Years of Manto

Modesty of Dress and Indian Culture: Suchi Govindarajan

Widely circulating just about everywhere, but for the unfortunate few who may have missed it…

I for one want to kiss the hem of her salwar/sari/jeans/other modest outfit.

Sir/Madam,

I write to complain about the abysmal standards of modesty I am noticing in Indian society. All bad things – sensationalist TV, obscene movies, diabetes among elders, pickpocketing, dilution of coconut chutney in Saravana Bhavan – are a result of Evil Western Influences. However, to my surprise, in this issue of modesty, even the Great Indian Culture (we had invented Maths and pineapple rasam when westerners were still cavemen) seems to encourage this.

The problem, sir/madam, is that revealing attire is being worn. Deep-neck and sleeveless tops, exposed legs–and these are just the middle-aged priests! Some priests are even (Shiva Shiva!) doing away with the upper garment. And I am told some temple managements even encourage this.

Read the rest of this brilliant and biting piece here.

On Josh Malihabadi’s death anniversary

On Josh Malihabadi’s 30th death anniversary, doing the rounds is this recently uploaded interview of the Urdu poet, amongst a rich archive uploaded on YouTube by Radio Pakistan.

Josh migrated to Pakistan only in 1958. About the loss of Lucknow, he says it was like losing the world. He says in this interview about a visit to Lucknow, where he asked a taxi driver, how is it going with all these Sikhs and Punjabis who have come to Lucknow. The taxi driver replies, we have taught them (Lakhnavi) etiquette!

Library.nu R.I.P

Amongst the competing visions of heaven offered by the various prophets and saints, my favourite remains the one conjured by St. Alberto Manguel. For him, heaven is a place where you can read all the books that you did not finish. It would be difficult for me – proud member of the tribe of bibliophiles- to imagine a better idea of paradise than this. I would even hazard a bet that many of you fellow tribe members would probably imagine yourself in this other world (with enough time) curled up in a comfortable sofa, opening a copy of Joyce’s Ulysses for the 28th time – saying finally this time.

But even within the order of the saints, one must respect the subtle rules of hierarchy and pecking order, and by that count St. Manguel would have to make way for the highest ordained of them all- the blind seer who saw everything- Jorge Luis Borges, who had much earlier been granted a vision of paradise and he declared that it was shaped like a library.

Caste and Exploitation in Indian History: Bharat Patankar

Guest post by BHARAT PATANKAR translated by GAIL OMVEDT

Introduction: The Process of Exploitation

Exploitation arising from the caste hierarchy is a particular feature of the South Asian subcontinent. There was no such exploitative system in other continents or in countries outside of South Asia. But since caste exploitation has been a reality for 1500-2000 years this shakes the belief that only class can be the basis of exploitation. And because of this we have to transcend the attempt to find a way only pragmatically and deal with the issue on a philosophical and theoretical level. Class has been theorized extensively in terms of exploitation; to some extent gender also, but not caste. Exploitation as women in various forms has also been a reality for thousands of years; this also is not through “class”. This reality from throughout the world gives a blow to the idea that exploitation can only be class exploitation. This can also be said of exploitation arising on the basis of racial and communal factors. Continue reading Caste and Exploitation in Indian History: Bharat Patankar

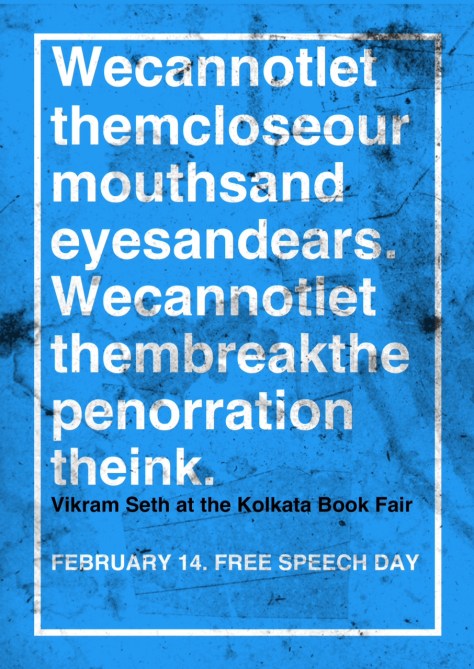

Flashreads for Free Speech: Readings for 14 February

Let this 14 February be Free Speech Day – the text below comes to us via NILANJANA S. ROY; for more, see Akhond of Swat or follow #flashreads on Twitter. Flashreads are being organised across India – see Facebook event page.

- Poster by Sanjay Sipahimalani

THE IDEA: To celebrate free speech and to protest book bans, censorship in the arts and curbs on free expression

WHY FEBRUARY 14? For two reasons. In 1989, the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering the death of Salman Rushdie for writing the Satanic Verses. In GB Shaw’’s words: “Assassination is the extreme form of censorship.” Continue reading Flashreads for Free Speech: Readings for 14 February

Rethinking Urdu Nationalism in Pakistan: Raza Rumi

Guest post by RAZA RUMI

Guest post by RAZA RUMI

Urdu has been a controversial language in Pakistan despite its official and holy status. The Bengalis rejected it way back in the 1940s when Jinnah, advised by a bureaucracy, with imperial moorings declared in that it would be the official language. Subsequently, Sindhis, Baloch and Pashtuns have also resisted the one-size-fits-all Urdu formula. Yet, Urdu has emerged as the functional lingua franca that connects Pakistan’s federating units, and its conflation with Islam and Muslim ‘nationhood’ remains the paramount narrative in Pakistan.

It takes arduous scholarship and infinite courage to author a book like From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (Oxford University Press, 2011). Dr Tariq Rahman, ironically, has worked as the Director of the National Institute of Pakistan Studies at the Quaid-i-Azam University and therefore his challenge to the mythical dimensions of ‘Pakistan Studies’ comes from within and not as an outsider. Sixty-four years after the creation of Pakistan, we have not arrived at any conclusion about our ‘national’ or cultural identity. Dr Rahman’s book if anything shatters the myths that we have built around Urdu; and therefore presents a valid alternative to Goebbelsian tone of our official history. Continue reading Rethinking Urdu Nationalism in Pakistan: Raza Rumi

At the Bend

Beyond the Four Corners of the Law and the Diggy Palace: Faiz Ullah

Guest post by FAIZ ULLAH

I.

Highstreet Phoenix, an upscale shopping mall, rose from the ashes of Lower Parel’s semi-functional Phoenix Mills in the late nineties’ Bombay. It has since successfully emerged as one of the most popular shopping and leisure destinations for the city’s affluent set. Highstreet Phoenix is just one of the many mills in the South-Central Bombay’s Girangaon that have been leased, sold or redeveloped in contravention of industrial and land-use policies and court judgements especially in the last two decades. These large swathes of urban land, two thirds of which was meant for low-cost housing, civic amenities and open spaces, are being fast converted into exclusive housing societies, office complexes and recreation zones that only a few can access and afford. Such tensions, some like McKinsey & Company (of Vision Mumbai report fame) would say, are inevitable, even necessary, for the cities that aspire to be world class.

Continue reading Beyond the Four Corners of the Law and the Diggy Palace: Faiz Ullah

To the Students and Faculty of Symbiosis University on the Censors in their Midst

Dear Students, Dear Teachers, Dear Friends at Symbiosis University, Pune

You are faced with an extraordinary situation. A symposium on Kashmir that was to be held in your institution with the support of the University Grants Commission, has been cancelled, postponed (see update at the end of the post) following complaints by activists of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (the student wing of the extreme right-wing militia that goes by the name of the RSS) against the proposed screening of a documentary film ‘Jashn-e-Azadi‘ (‘This is How We Celebrate Freedom’) by the well known filmmaker Sanjay Kak. These complaints, which could more accurately be called threats, have unfortunately received the tacit endorsement of senior police figures in Pune and seem to have met with the approval of your principal. (Thanks to The Hindu – see links above – for the two balanced reports on this issue.) While the seminar may or may not be held (it stands ‘postponed’ as of now) the administration of Symbiosis have succumbed to the insistence of the right wing groups that Jashn-e-Azadi’s screening remain cancelled. Continue reading To the Students and Faculty of Symbiosis University on the Censors in their Midst

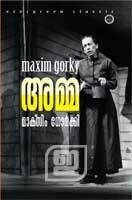

The Book of Mothers: P K Medini

“P K MEDINI still recollects the day when she first sang for the election campaign of the Communist party. Now, six decades later, the spirit isn’t one bit lost for the veteran singer. Medini, 78, says she sang first for Communist leader T V Thomas. Since then, she had been a regular presence at the election campaigns of the Communist party.” From expressbuzz April 1, 2011

Delhi-based journalist JACOB SEBASTIAN sent us his translation of a piece by PK Medini in Malayalam (published in the journal Mathrubhumi earlier this month ), along with a background note that he wrote for our readers.

The following piece was written by P.K. Medini, the one-time ‘singing sensation’ of the Communist Party in Kerala. It originally appeared in the Matrubhumi Weekly, as part of a series where people talk about their favourite books. It offers a glimpse of a time and place where literature and books and the whole culture of reading, mattered in an urgent and vital way.

The following piece was written by P.K. Medini, the one-time ‘singing sensation’ of the Communist Party in Kerala. It originally appeared in the Matrubhumi Weekly, as part of a series where people talk about their favourite books. It offers a glimpse of a time and place where literature and books and the whole culture of reading, mattered in an urgent and vital way.

She gives us an intimate snapshot of the new reading culture at the time when it was putting down its first tentative roots. For someone who readily admits that her own reading was ‘impoverished’, she shows a keen awareness of the power of ideas – and of books as objects of an almost talismanic power – andreveals their absolute centrality to the social and political transformations of the time.

If such a thing is unimaginable to us today, even more unexpected are the ways in which it actually played out – the many tortuous routes the word had to take before it could become flesh (she calls it ‘social reading’). She also has a sharp eye for how political propaganda actually works ‘on the ground’. Along with other movements, Medini’s party too can take some credit for the fact that life in Kerala isn’t so desperate today that a society could catch fire from a book.

Paramakudi – Six Poems: Ravikumar

In September last year, the Tamil Nadu police killed six Dalits in a firing incident in Paramakudi town of Ramanathapuram district. This guest post by RAVIKUMAR is a set of six poems on the Paramakudi killings. The English translation by RAVISHANKER is followed by the Tamil original. For more on the incident, see articles in Kafila archives by V. Geetha and Bobby Kunhu and over at Atrocity News, a fact finding report (.pdf).

Engaging Lankans in Black Politics on MLK Day

In approaching Martin Luther King Jr., Day, I inevitably think about the politics of figures and the generation of King and Malcolm X. That generation and the Black politics they engendered had a lasting impact on the US and the World more broadly. Coming with decolonisation in Africa and elsewhere, King, Malcolm X, the radical youth they inspired and their contemporaries such as Frantz Fanon and C.L.R. James transformed our conceptions of race and class, advancing anti-imperialist and anti-colonial visions to engage formidable questions of Black politics in the West. In a piece written with Jinee Lokaneeta as part of the monthly column ‘Beyond Boundaries’ of the South Asia Solidarity Initiative (SASI), in the South Asian Magazine for Action and Reflection (SAMAR), we began with Manning Marable and C.L.R. James, and the importance of a turn towards critical solidarity engaging questions of race and class.

Here, I want to think about the contributions of South Asian intellectuals, or more specifically Lankan intellectuals in the context of Black and Third World politics. In fact, there are two major Lankan intellectuals belonging to that generation of King and Malcolm X, who are increasingly not known to the younger generations of Lankans. A. Sivanandan, the editor of Race and Class and Director of the Institute of Race Relations in London and the late Archie W. Singham, long-time intellectual and professor based in New York are two such figures who have made a major mark in Black politics. Indeed, they can give us a sense of the possibilities of political struggle and the historical and philosophical potential of Black politics. It is my contention that engaging the politics of Sivanandan and Singham is all the more important at the current moment, as South Asians in the Diaspora are increasingly becoming agents of Western power despite the shifting terrain of politics in the West with the global economic crisis. Continue reading Engaging Lankans in Black Politics on MLK Day